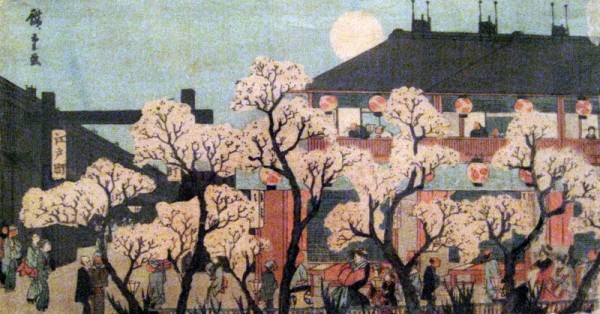

It all started when Japan opened its doors to the West in the 1850s and Japanese works of art infiltrated Europe, the centre of interest being in Paris. By 1867 French Impressionist artists such as Claude Monet turned their attention to the popular ukiyo-e (‘pictures of the floating world’) woodblock prints and illustrated books that depicted life in the urban centres of Japan. The ‘floating world’ derived from Buddhist philosophy, referring to the transience of nature and the intense pleasures of everyday life, in particular those ‘pleasure quarters’ of Edo. Geishas, cherry blossom, kabuki actors, tea rooms, snowy landscapes, moonlit streets and seascapes — life in Japan during the Edo period (1603-1868) — was captured in these ukiyo-e prints. The French term, Japonisme, was used to describe the European assimilation of stylistic and design principles from Japanese art: the cropping of key pictorial elements, reduced emphasis on perspective and shadow to suggest depth, black outlines separating distinct areas of pure, flat colour. A perfect example is the featured image: Utagawa Hiroshige’s ‘A Spring moonlight scene at Shinyasgiuma in Edo’ (1840s) in which partial views and asymmetry are incorporated into this striking compositional design. It can be said that Japanese woodblock prints contributed to the nineteenth-century revolution in European art and inspired twentieth-century Australian artists, especially women printmakers, who combined elements of Japanese woodblock printing with Western practices to create innovative visions of the world around them.

And so, after many false starts over the past few weeks, I boarded a train in Melbourne bound for Bendigo (a 4 hour return trip) to catch the art exhibition, Japanese Visions. The show draws exclusively from the Bendigo Art Gallery collection and explores the influences of Japanese woodblock printing on Australian artists. Over 70 works are on display in a rectangular room painted off-white. Approximately half the works are nineteenth- and twentieth-century Japanese woodblock prints; the other half are prints produced by Australian artists. Some of the leading proponents of modernism in Australian art, such as Margaret Preston, were attracted to woodblock and linocut printing, which peaked in popularity throughout the 1920s.

The exhibition starts with the ukiyo-e prints from Japan, a good place to start. However, when you first enter the exhibition space it isn’t immediately obvious to turn left around a barrier and start here with the 19th century Japanese woodblock prints which are hung along one side of the room (and the Australian prints along the other side). Temporary walls in the middle of the floor-space display both Australian and Japanese works. There is a loose chronological order and in many cases the layout is determined purely aesthetically – this became a little confusing. However, the lighting is perfect – not too bright, not too low (light levels need to remain low to protect these works on paper).

French painter, printmaker, sculptor and ceramicist, Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), collected ukiyo-e prints. He wrote to his friend and fellow painter, Emile Bernard in 1888: “Look at the Japanese who are certainly excellent draughtsmen, and you will see life depicted in the open air … without shadows, colour being used only as a combination of tones, diverse harmonies . . . “ Gauguin used colour zones with black outlines to flatten the picture plane, achieving depth by lines of vision, often with a high horizon and strong diagonals that carve up the otherwise flat space. He was labelled a Post-Impressionist because he flirted with the realm of abstraction through expressive pattern and decorative form.

Eventually, the visitor to Japanese Visions comes across the term: shin hanga (new print) and sosaku hanga (creative print). By the early twentieth century the Japanese ukiyo-e tradition evolved into this new woodblock printing that adopted Western techniques, such as perspective and shading. Hiroshi Yoshida’s ‘Iris Garden in Harikiri’ (1928) is a fine example (Image 2); note the more romanticised subject matter, the increased perspective and range of colour. Perhaps a wall text explaining this twentieth-century artistic exchange between the East and the West would be helpful as the transition from ukiyo-e prints to the new, more modern, printing aesthetic is too seamless.

Australian artists at the forefront of modernism in Australia during the first few decades of the twentieth century (such as Thea Proctor, Ethel Spowers, Margaret Preston and Lionel Lindsay) were influenced by Japanese woodblock prints and adapted Japanese aesthetics to develop their own innovative woodblock and linocut printing designs. Their art conveyed a vision of our relationship with nature and, modern life. Like Monet and Gauguin, these Australian printmakers gained confidence in shifting away from illusionistic depiction resulting in a more abstract form evoking variation of season, hour, light and mood. Ethel Spowers’ ‘The Green Bridge’ (1926) is a colour linocut (Image 3) that echoes these qualities. Spowers even printed her initials in monogram format (bottom right hand corner), emulating the tradition of Japanese ukiyo-e artists. However, as charming as these woodblock prints are, they are not revolutionary; a more aggressive and creative Australian modernism came later in the work of artists such as Grace Cossington-Smith and Sidney Nolan.

The last time I saw Bendigo it was stuck in a time warp, but a large part of this historic town’s rejuvenation has been the success of the Bendigo Art Gallery in attracting visitors to its admirable collection of European and Australian art. Thanks to its visionary director, Karen Quinlan, there have been many innovative temporary exhibitions in the last couple of years. Take this opportunity to support a regional art gallery at 42 View St, Bendigo. Japanese Visions closes on 27 January (open daily, 10am-5pm. Free)

If you want more Japanese art then visit the National Gallery of Victoria’s newly renovated Asian art gallery; a stunning curatorial and design achievement, not to mention the amazing collection of artworks.