Words are powerful and can ‘paint’ a picture, particularly words used in poetry that resonate and stay with us. Favourite passages in novels are often read and reread to relive that feeling and scene, or that memory of the first time they were read. Visual art stimulates an immediate sensation through sight and is not tied to language. A work of art does not require a certain standard of literacy to understand the artist’s intention or to appreciate the skill embodied within. Pictures transcend language barriers and can be understood by people from diverse cultural backgrounds. One of the downsides is that those without sight can only imagine the work of art being described by someone else.

Words and pictures both have the ability to capture a moment and transport readers and viewers. Impressionist painter Claude Monet painted ‘Railroad Bridge, Argenteuil’ in 1874. The painting is owned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art and eloquently described on their website:

A small sailboat drifts along the water in this tranquil scene. Warm, golden light brightens the bridge’s white pillars and the boat’s sail. Their reflections in the water add pink, yellow, and orange hues to the blue of the river. Along the top of the bridge, a train chugs along, letting out puffs of smoke that drift across the sky. A gentle wind pushes the boat across the calm river below. Claude Monet, the French artist who created this work of art, enjoyed painting the outdoors directly from observation. He appreciated the variety of colours in the sky, water, plants, and trees, especially those seen at sunrise and sunset.

This description is probably unnecessary because the viewer can ‘read’ the picture, but I enjoyed the fluid commentary that depicts each aspect of the ‘tranquil scene’ using soporific words such as; drifts, hues, chugs, puffs, drift, gentle, calm.

A contemporary of Monet’s was Realist writer Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880) who wrote images across the page; here is an extract from ‘Sentimental Education’ (1869) that describes a train similar to Monet’s train in ‘Railway Bridge, Argenteuil’, with the trailing smoke of the steam engine:

Now and then, at the foot of the wooded hills, the smoke of a railway engine unfurled in a horizontal line, like a gigantic ostrich feather whose tip kept blowing away.

Both Monet and Flaubert give readers a vivid notation of a specific time and place — you may prefer the colour and the brushstrokes rather than the words. The simile in Flaubert’s sentence is perfection, as is the simile in the next sentence in which Flaubert continues to enrich the reader’s imagination with visual detail, probably in excess of requirements of the storyline:

Sometimes the sunbeams, coming through the venetian blind, would stretch what looked like the strings of a lyre from ceiling to floor, and specks of dust would whirl about in these luminous bars.

We see the everyday in this romantic writing that has been smuggled into Flaubert’s realist novel. The plot stands still while readers immerse themselves in these exquisite moments. Julian Barnes, author of many books, wrote in ‘Keeping an Eye Open’(2015) that ‘a painter whose picture is given a five-second glance by some window-shopping gallery goer might well envy the sheer time a reader is willing to spend with a writer. Redon declared literature ‘the greatest art’.’ Odilon Redon (1840-1916) created strange dreamlike paintings and drawings.

French artist Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), a prominent figure in the Realism movement made this bold statement about art:

I hold also that painting is essentially concrete art, and can consist only of the representation of things both real and existing. It is an altogether physical language, made up of what is visible. An abstract object, invisible or non-existent, does not belong to the domain of painting.

Maybe what Redon and Courbet are saying is that words allow for a deeper level of complexity, nuance, and precise expression, particularly when communicating abstract ideas, emotions, and detailed information that can be difficult to fully capture with visuals alone. However, although Barnes admits that paint can ‘render emotional states and complexities normally conveyed at novel length by means of colour, tone, density, focus, framing, swirl, intensity, rapture’, he can see a story out of the ‘moments frozen by Courbet and Degas’. A few years ago, I taught a creative writing course where each student had to choose a painting that resonated with them, whether it was a landscape, a seascape, a scene in a city or the countryside, or a portrait, and tease out a narrative from it. There were some fascinating results.

However, I wonder if words would do justice to George Stubbs’ painting, ‘Whistlejacket’ (c.1762; image below). I could prattle on about the blank olive background setting off the rearing racehorse as a solitary, almost metaphysical being, quivering with energy and readiness, his nostrils, eyes and ears on high alert. This radical treatment of an animal at the peak of his beauty came out of the period of the Enlightenment in Europe when nature and philosophy were the new buzz words. I could write about the lively ‘line of beauty’, glistening coat, rich colour and majestic presence. Apart from the breathtaking physical beauty of Whistlejacket in painted form, there is a resonating psychological intensity.

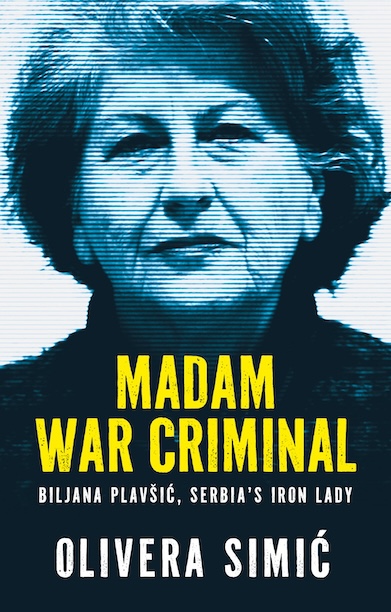

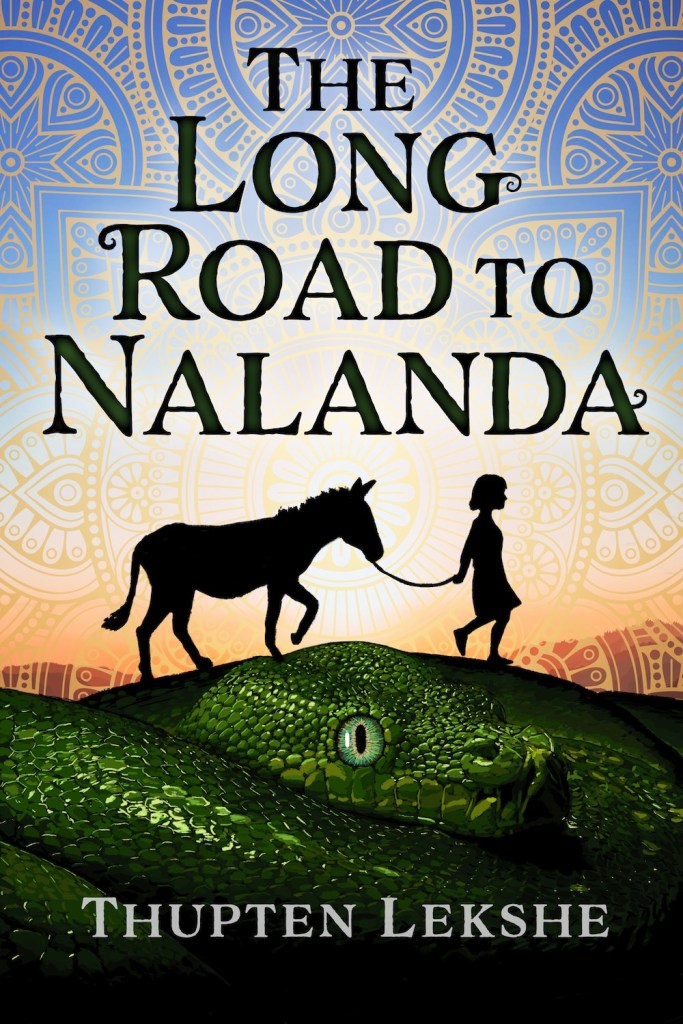

According to Barnes, ‘Flaubert refused to allow his novels to be illustrated’. He wanted the reader to imagine the scene or build an image of a character. I agree. I’m not a fan of book covers with images taken from ‘somewhere’ to represent the main character. I’d much rather create my own internal picturing of a character or a setting.

Essentially, painted imagery can evoke many responses and emotions, but it is static and occupies space. Words are fluid, providing rich layers of imagery, meaning, context and memory.

Need an editor?

Need an editor?

Having your writing project edited before submitting it to publishers can prove invaluable. In an economic climate where authors face heavy competition to be offered a publishing contract, your writing needs polish. An objective assessment and edit by an experienced professional editor can be costly, but based on the feedback I’ve received, your submission will have a greater chance of being successful.

If you’re ready to have your manuscript assessed, whether it is a complete manuscript or a work-in-progress, then you’re welcome to email me (denise@denisemtaylor.com.au) via my contact page with a brief overview of your project and I will respond within a few hours.