Choosing the intimate first-person point of view to write a scholarly book or a fictional narrative is challenging. Point of view (POV) is the perspective from which an author writes a story or presents information. There are three points of view (viewpoints) — the first-person POV (I, we), the second person (you, your), and the third person (he, she, they). Sometimes non-fiction authors don’t realise they are mixing all three POVs until it is pointed out by an editor. Memorable first-person narratives suck you into a character’s world, but there are pitfalls.

First-person POV in non-fiction

The non-fiction author presents information/arguments that are conveyed through the persona of the writer. In some non-fiction writing, particularly research or news articles, the author’s presence is notably absent. There is skill involved in keeping the voice of the writer out of the reader’s head. The best research studies, in my opinion, are formal, with the first-person POV, and the use of ‘I’, confined to the methodology or the presentation the results of research. However, even though the methods section is personal to the researcher, it can still be written in the third-person POV in a compelling way rather than using the first-person POV. Then overuse of ‘I’ is often viewed as a means of persuading the reader in an emotive way. There are no hard-and-fast rules; I often suggest experimenting with different points of view and then deciding, perhaps with an editor’s advice, which tone best suits the topic, purpose and target readers.

I recently reviewed a scholarly manuscript that presented a unique idea incorporating the academic’s experience; however, the author kept drawing in the reader, at times asking questions, as if unsure. For example (this example has been modified from the original), I think performance in this instance is crucial in understanding the concept. Do you enjoy being taught by someone who uses performative body language? I suggested avoiding the tenuous first-person POV, I think, and deleting the question. The following sentence is more authoritative than the original and yet clearly suggests a personal view. Performance in this instance is crucial in understanding the concept. Body language can be an effective teaching tool.

In essence, it’s important to remember that the first-person POV is subjective, and sometimes comes across as being persuasive and too personal; this could undermine the writer’s intention when used in non-fiction writing. Third-person POV is more objective and adds credibility to any non-fiction work.

First-person POV in fiction

In my experience as an editor, perhaps the most important decision a fiction writer makes is the choice of a point of view (viewpoint). A story cannot be written without a narrator, but there are many times when an inexperienced fiction writer chooses the first-person POV and loses control of the character-narrator.

Being inside the mind of a character can be a thrilling reading experience. But this intimacy comes at a price and there is a distinct possibility that the character who is telling the story ‘takes over’ because her/his ‘voice’ is too dominant and the supporting cast is pushed into the background — even the plot can take a back seat to this ‘hero’ narrator. So, if your first-person narrator has a ‘larger-than-life’ personality, it’s crucial to balance this voice with strong supporting characters and a ‘good’ plot. Alternatively, the ‘witness’ narrator does not remain focussed on her or his thoughts and actions but is observant of other characters and events.

Too many sentences beginning with ‘I’, too many internal monologues and too much introspection can kill a reader’s interest in the first few pages. But if handled with care, the first-person POV can be satisfying, immersive reading. Note the following extract from J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye — Holden Caulfield is telling us exclusively about himself, his own feelings and thoughts, but the intimate way of expressing them is honest and we immediately feel sympathy, maybe even connection.

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.

Written by another author, this may have had too much ‘poor-me’ sentimentality, but Salinger has avoided any emotional rhetoric. I’ve just finished reading Pip Williams’ historical novel, The Dictionary of Lost Words. It is written from the main character’s viewpoint. Esme draws the reader into her world. As a child she spends time under the sorting table in Dr Murray’s Scriptorium, which is the beginning of her life spent recording words used by working-class women. Williams uses the ‘hero’ and ‘witness’ mode of first-person narration. Esme is observant, and the characters around her, such as her father, Lizzie and Gareth are varied and interesting. Esme never dominates the narrative, and when something momentous happens in her life, there is simplicity in the way the event is captured; for example, when her father has a stroke and dies: ‘When I arrived at the Radcliffe Infirmary, they told me he was gone. Gone, I thought. It was wholly inadequate.’

And there is a similar simplicity in the poignant ending of Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms (published in 1929, it is a fictional first-person account by Frederic Henry, an American ambulance driver in Italy during World War I) which never fails to ‘grab’ me when I re-read it. I can’t imagine this final scene being written in the third-person POV. There are no clever words or language, no intrusive commas, and no expressive adverbs; but the reader ‘feels’ the tension and grief. Henry’s lover dies in childbirth and the final sentences are drained of emotion:

‘You can’t come in now,’ one of the nurses said.

‘Yes, I can,’ I said.

‘You can’t come in yet.’

‘You get out,’ I said. ‘The other one too.’

But after I had got them out and shut the door and turned off the light it wasn’t any good. It was like saying goodbye to a statue. After a while I went out and left the hospital and walked back to the hotel in the rain.

Choosing the first-person POV narration to tell a story or write a non-fiction book needs careful consideration to avoid the pitfalls. But it’s worth the challenge!

If you are ready to have your writing edited, whether it only needs a light edit or a more detailed structural edit, or if you would like an assessment of your unpublished manuscript, then please email me via my contact page or directly at denise@denisemtaylor.com.au with a brief overview of your specific needs and the word count of your manuscript.

My editing is based on the Australian Style Manual (ASM) unless an author has been commissioned to write a book using the publishing house style guide.

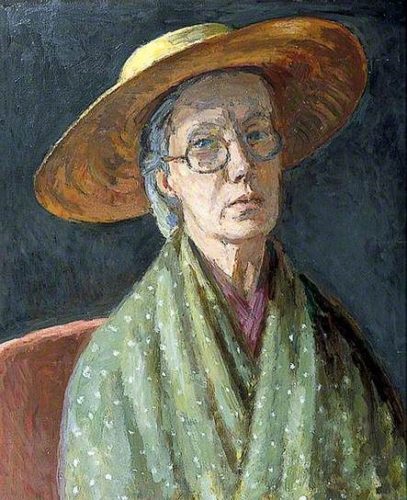

Featured image:Vanessa Bell, ‘Self-Portrait’, 1958, oil on canvas, 45 x 37 cm, The Charleston Trust, © The Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy of Henrietta Garnet