Private art galleries are not only imbued with the presiding spirit of the collectors, which is consolidated in the choice of art works on display, but also by the nature of the gallery’s building and its site. Whether the building is a new build or a domestic residence converted into a museum to exhibit the owner’s art collection, there is always innuendo about it being a monument to vanity. Over and above these considerations, it is the degree to which the private art collection engages with the public that determines the success or failure of the enterprise. It seems to me that even if the quality of the art is variable, visitors are less likely to be intimidated in a private gallery than they are in huge public galleries. In recent years, public-funded art institutions have increasingly bowed down to our media-driven world as they try to prove relevance to the younger generation, and keep afloat.

Many public art galleries are turning into a frantic free-for-all, with big-name exhibitions, participatory experiences and digitalised information being a draw-card for visitors, driving up numbers with the hope of return visits and increased membership to bolster funds. But do mega shows and interactive exhibits crammed into ground floor spaces with shopping and coffee opportunities really ‘educate’ the public about the broad spectrum of art?

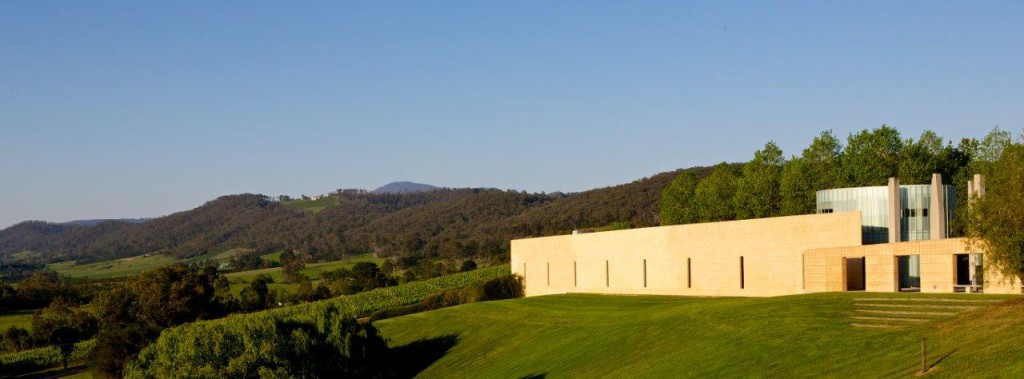

I am concerned that major public art galleries such as my local National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne are being turned into theme parks with visitors being enticed to window shop and play rather than being encouraged to engage closely with the works of art on display. Aggressive fundraising activities are forcing a flurry of ‘events’ and the exhibition schedule is breathless—here one day, gone the next—with associated interactive children’s play areas—prams at ten paces. On the other hand, privately-run galleries such as Victoria’s Tarrawarra Museum of Art (TWMA) and Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery are an opportunity for viewers to experience more narrowly-focussed, less-populist art exhibitions that encourage individual thought-processes about the art on display, usually in more relaxed environments, which must enhance the visitor’s experience.

The new era of building private museums is often dismissed as riding the wave of popularity of ‘cultural destinations’, and as an overt display of wealth by rich individuals; but I’m on board, enjoying the ride. Collectors often have extravagant plans for their museums such as inventive architecture to not only reflect their personal, often idiosyncratic tastes in art, but, as is the case with TWMA on the outskirts of Melbourne, and the Maeght Foundation in Saint-Paul-de-Vence in France, to blend with the natural environment. On the opposite end of the scale are the flamboyant private museums that are being built around the world. The Museo Soumaya in Mexico City, owned and operated by the Carlos Slim Foundation, is an hourglass-shaped structure smothered with more than 16,000 hexagonal aluminium tiles that reflect light. Opened in 2011, the internal spaces are carefully designed to display art in a thoughtful and seductive way. Architect, Juan Carretero, wrote an article in The Independent when the Museo Soumaya opened:

There is a narrow entrance, after which the main atrium opens up and impresses merely by dint of its scale, the sensuality of the lines and the purity of its soft snow-white walls which hug [Rodin’s] ‘The Thinker’ without taking away from the energy of its pondering posture.

The Museum of Old and New Art (MONA), brainchild of art collector David Walsh (born 1961) and Melbourne architect Nonda Katsalidis, also opened in 2011 just outside Hobart—a vast underground private museum that has quickly become one of the cultural ‘must-sees’ in Tasmania, if not Australia. The building attempts to blend and merge with the environment, formed by and from the surrounding rock. The vertical and horizontal interplay of interior walkways and lifts between the three underground floors create a seductive and dark Piranesian mood that suits Walsh’s eclectic mix of art and artefacts, and his eccentric nature. There is no denying that this art museum reflects Walsh’s quirky approach to buying and displaying art—a distinctive philosophy that pits old art with new, but never against each another.

In essence, a private museum is a modern-day version of the original museum set up in the collector’s home: the eye-boggling Wunderkammer showcases and ‘cabinets of curiosities’ crammed with natural curiosities and art objects on show for the pleasure of a chosen few. MONA’s success must be attributed to Walsh’s open invitation for the public to explore and respond to his collection on an individual basis without any didactic intent—people can think whatever they like about David Walsh’s art, and they don’t have to like it or try to understand it. An iPod, which is presented to the visitor on entry, senses where the visitor is in the gallery and provides information about the art at close range—innovative and welcome for some, a distraction and an annoyance for others—take it or leave it. Walsh thrives on the backlash from conservatives. No wonder MONA has been labelled the ‘Temple of David’. But what about the traditional temples of high culture?

As innovative as public galleries aim to be, they are all rigidly defined by traditional curatorial departments and collection policies. No amount of window dressing and draw-cards, such as big-money blockbusters, after-hours entertainment and popular fashion shows, can alter the fact that public galleries are all products of nineteenth-century conservatism. Large public art institutions offer excellent, scholarly symposiums, which satisfy their commitment to higher education for those who are interested; however, these days, public galleries are obsessed with appealing to mass culture. Art curator and writer, Peter Timms, asserts that public art museums and galleries have “developed something of a split personality” due to political- and financial-survival pressure to meet modern demands: “serious and fun at the same time—both elitist and populist”. Timms concludes that “the art museum is an institution in crisis”*. As a consequence, I am enjoying the less-neurotic delights of smaller public galleries, such as the Hawthorn Town Hall Gallery in the eastern suburbs of Melbourne that celebrates and fosters a strong sense of community and offers exhibition space to local, national and international artists at varying stages in their careers.

There is no doubt that the NGV has a world-class collection, but it has become conflicted by broadening the scope of what’s on at any one time: large contemporary installations, architectural design exhibits, children’s festivals, blockbusters, and ‘minor’, expensive-looking exhibitions. Under the direction of Tony Ellwood, the NGV has increased its public engagement programs that support the Gallery’s frantic exhibitions calendar—spot the frazzled curators. Ellwood is often seen striding purposefully through the NGV gallery spaces eyeing the latest ‘hang’ with a serious countenance, closely followed by assistants with Ipads. It is apparent that the combined thinking of those in the lofty echelons of the NGV obsesses with the idea that the more visitors treading their hallowed ground, the more likely their funding will increase; it doesn’t matter if too few visitors make it to level three, as long as the paid exhibitions, cafés and shop are filled to the brim. But is in-depth appreciation of art at risk of losing out to the public’s growing need to be entertained and fed new information in rapid-fire succession?

To appreciate and understand works of art to the best of our ability, we need to learn to stop and look at works of art—take time to contemplate what is before us and allow our emotions and perceptions the freedom to respond. Tragically, art in public galleries is being crowded out by a whirlwind of tour groups, and visitors who only want to stand before a work of art for as long as it takes to snap a photo on their smart phones. Instant gratification and immediate entertainment is what most big public gallery visitors seem to want, and if they get it, word gets around, attracting even larger crowds, ending up being equivalent to a trip to the supermarket—get what you want, take a few photos to prove you are culturally cool, and get out. Consequently, is demand for guided tours of public art collections on the decline, especially amongst younger visitors?

The NGV offers four 50-minute daily tours at each gallery location (NGV International and NGV Australia), when surely one in the morning and one in the afternoon would suffice, and help reduce traffic. The National Gallery in London only offers two talks/tours per day. Each NGV tour includes an average of between 15 and 20 art works, which often involves a lot of walking to navigate the segmented floor layouts, and just a few minutes in front of each art work. In comparison, London’s NG only includes three to four art works in 60 minutes. NGV tours are led by volunteers (who have had a NGV-run, crash-course in art history) regurgitating pre-packaged facts and ideas, whereas guided tours on offer at London’s Trafalgar Square gallery are taken by “Gallery lecturers”, usually curators. The recent free NG tour I took in London was conducted by a curator and I was captivated by his intimate knowledge of the three paintings he chose. Similarly, most private galleries only offer talks by members of staff, and only take privately-organised guided tours; others have limited guided tours (one or two a week), usually undertaken by art history graduates and curators.

Private art collections exhibited in domestic residences, often in the house of the collector, add a mouth-watering experience for the viewing public by attaching a meaningful narrative to the collection through a more direct connection with the collector. For example, Sir John Soane’s Museum and the Wallace Collection in London, and the Frick Museum in New York City. They are enduring expressions of the relationship between the owner and his or her art collection. The eclectic collection crammed into Sir John Soane’s Museum features Soane’s architectural drawings and works of classical art that he collected on his Grand Tour of Europe. This house-museum is even more representative of the original Wunderkammer because there is a feeling that John Soane (1753-1837) is still living here, delighting his friends and family with his ‘curiosities’. Henry Clay Frick (1849-1919) was an American self-made millionaire with limited knowledge of high culture but who sought out the best European ‘old’ art from the most reputable art dealers. His collection is housed in his French-styled villa in Fifth Avenue, which he designed himself. Today, visitors to these private houses are not only able to experience art and artefacts of an extraordinary quality and history, but at the same time gain a valuable insight into the owners’ life and collecting practices. Many may dismiss these museum donor memorials as stuffy, pretentious and self-indulgent, but the intimacy of houses that display the much-loved art of the owner is unquestionable, and unattainable in public institutions.

Private museums are often the result of a collaborative effort—a labour of love— between the connoisseurs who collect the art, the architect, and the artists whose works are displayed there. Situated on a pine-forested hill just outside the French village of Saint-Paul-de-Vence in Provence, the Maeght Foundation is an example of this unique collaboration. I visited this museum of art a few years ago (built in 1964), and it reminded me of the peaceful surroundings of TWMA and its architect-designed building that nestles into a hill surrounded by vineyards, and which reflects the modesty of its founders, Eva and Marc Besen, passionate collectors of Australian art since the 1950s.

Similarly, the Maeght Foundation, designed by Jose Luis Sert, integrates the beauty of the landscape with modern art and architecture that satisfies the objectives of collectors Marguerite and Aime Maeght: to reflect the essence of the twentieth-century art on display, such as Joan Miro’s labyrinth, George Braque’s pool and Giacometti’s sculpture terrace. This bold, innovative, and not-for-profit private enterprise does not receive a subsidy from the government, and, as such, has complete freedom in the choice of acquisitions as well as flexibility in the way the museum is run, subject to the approval the Foundation’s Board.

I have wielded a broad brush to this comparison of public and private art museums, and there is much more to be said. It goes without saying that I will always be a regular visitor to public art galleries that are largely funded by the tax-payer, but, increasingly, I choose my time carefully so I can meditate on, and marvel at, old favourites and new art that keeps my mind open to changing patterns in the visual arts. Having to tussle with blockbuster crowds, noisy school groups, guided tours, and tourists taking selfies of themselves in front of art, is diminishing my enjoyment. We should celebrate the burgeoning of private museums around the world, great and small, and the freedom they have in relation to collecting and exhibiting, unburdened by the public gallery’s schizophrenic need to satisfy bureaucracy, traditionalism, funders, and a new generation of gallery-goers.

*Peter Timms, ‘A Post Google Wunderkammer: Hobart’s Museum of Old and New Art Redefines the Genre’, Meanjin, 70/2, 2011, pp. 31-39.

Featured image: © Wallace Collection Museum-House

Post-script: In July I will be reporting on my experience of the newly-renovated Emery Walker Museum-House in London.