These days, it is cool to poo-poo the pursuit of beauty in art, but avant-garde writers and artists in late-nineteenth-century Europe, particularly in the hedonistic capital of France, celebrated the power of beauty to transform the beholder. English literary genius, Oscar Wilde, was notorious as the witty spokesman of Aestheticism and its bold declaration that art should be independent from life, existing solely to create beauty without any moral purpose or narrative constraint. In a letter to the editor of the St James’s Gazette (26 June, 1890) Wilde wrote that the “function of the artist is to invent, not to chronicle … Life by its realism is always spoiling the subject-matter of art.” This concept of art-for-art’s-sake and the search for a new ideal of beauty to transcend the ugliness of industrialisation and materialism ran counter to the overwrought morality and staidness of Victorian England—tensions ensued.

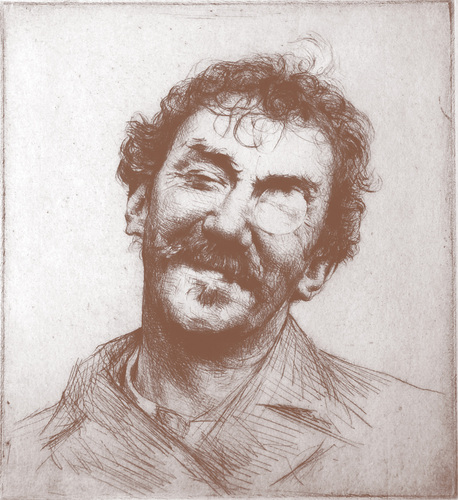

Mortimer Menpes (British, 1860–1938), ‘Portrait of Whistler’, c. 1880s, drypoint and etching, Gayle McJunkin Collection.

Another leading exponent of Aestheticism was American-born, European-based, James McNeill Whistler (born in 1834): painter, printmaker and designer. He was twenty years older than his fellow Aesthete, Oscar Wilde, and a renowned extrovert, who ridiculed the sentimentality and piety of his age. The Aesthetic Movement was all about rebellion, and Whistler is often thought of as the most controversial, and certainly the most influential, painter of Aestheticism. He moved to Paris in 1853, soaking up impressionistic techniques and transporting heady ideas across the Channel to London, where he finally settled in 1863. His declaration of the supremacy of beauty was striking, proclaiming that art was a means of conveying the exhilaration of personal stimulation through colour and form.

“Nature contains the elements, in colour and form, of all pictures, as the keyboard contains the notes of all music. But the artist is born to pick, and choose, and group with science, these elements, that the result may be beautiful.” James Whistler, 1885, Mr Whistler’s Ten o’Clock lecture.

In the 1870s Whistler was pre-occupied with portraits as a means of conveying his attraction to simple forms and complex, yet subtle, colour harmony. He extracted the essence of fashion, even in the simplest costume, to fit his art-for-art’s-sake philosophy, which often placed greater emphasis on the formal elements of line and colour than the identity of the sitter.

James McNeill Whistler, ‘Symphony in Flesh Colour and Pink: Mrs. Frederick R. Leyland’, 1871-74, oil on canvas, The Frick Collection, New York

Between 1871 and 1874, Whistler painted the portrait of Frances Leyland, wife of his patron, the wealthy British tycoon Frederick Leyland, called Symphony in Flesh Colour and Pink: Mrs. Frederick R. Leyland. This is a complete statement of Whistler’s Aestheticism with its references to music, colour, and translucent female beauty. The patterns of the matting offset the naturalistic flowering almond branches, a nod to Whistler’s fascination with the flat, decorative forms of Japanese woodblock prints. He even designed the beautiful pink chiffon, multi-layered gown worn by Frances Leyland (with whom he had an affair) to harmonise with the décor of the room, which he also designed. The portrait is such a fabrication of beauty in its exquisite design and colouring that Whistler’s contemporary, and fellow Aesthete, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, wrote of it: “I cannot see that it is at all a likeness”. This was a compliment; the Aesthetes promoted the concept that the work as an art object with qualities of beauty was more important than the subject matter.

James McNeill Whistler, ‘Arrangement in Grey and Black, No 1’ (Portrait of the artist’s mother), 1871, oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

In the same year that he began to paint the portrait of Frances Leyland, Whistler also painted the portrait of his ageing mother, Anna Whistler: Arrangement in Grey and Black, No.1 (Portrait of the artist’s mother), and probably his most recognisable painting worldwide. Although the painting resides in Paris’ Musée d’Orsay, Melbourne’s National Gallery of Victoria is currently running an exhibition with this famous painting as its focus. Greys and silvers, whites and blacks shimmer across the canvas with the restrained beauty of a Japanese screen. Whatever Whistler felt for his mother, this portrait of her does not show it, nor does the viewer gain any idea of the sitter’s personality. The painting’s original title, its tonal qualities and formal purity, are clear indicators of Whistler’s aesthetic principles.

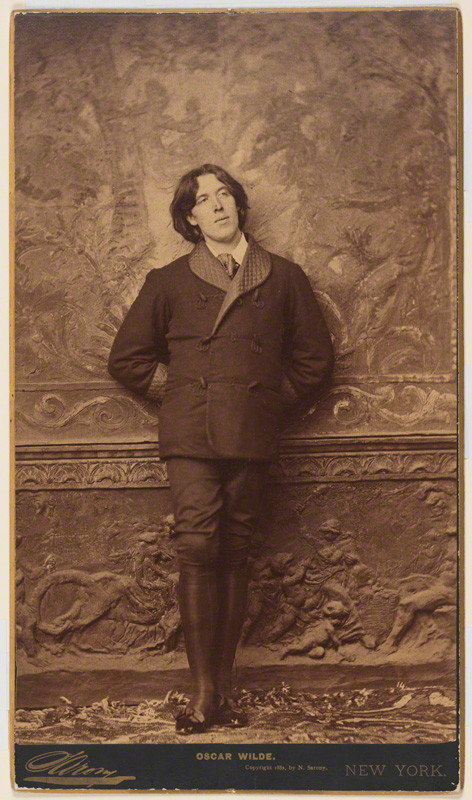

Napoleon Sarony, ‘Oscar Wilde’, 1882, albumen panel card, 305 x 184 mm, National Portrait Gallery, London

In 1873, the students of Oxford, including Oscar Wilde, were inspired by a very bizarre book, which became the literary manifesto of the Aesthetic Movement: The Renaissance by Walter Pater: a vision of life as pure sensual experience and a manifesto for hedonism. Wilde became the high priest of the movement that Pater launched. He became a celebrity, taking the lead in ‘aesthetic’ fashion, often dressing in knee-length velvet breeches, silk stockings and fur. Towards the end of the nineteenth century there was even a flourish of flamboyant experimentation in ceramic design, with some obvious associations to Oscar Wilde’s dandyism and Aestheticism in general.

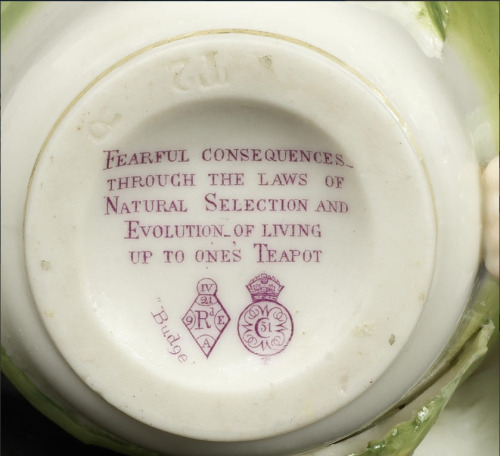

Worcester Royal Porcelain Co., ‘Aesthetic teapot’, 1882, porcelain, Dr Robert Wilson Collection, NGV, Melbourne

Humour and satire are entwined in the Aesthetic teapot (images above) produced by the Royal Porcelain Co. in 1882. The Janus-faced teapot is decorated with foppish, limp-wristed male and female Aesthetes. They both wear a purple bonnet; the spout and handle are formed by their arms. The lady’s smocked blouse has a ruffled collar and a large lily attached at the front; the long-haired young man wears a jacket with a pilgrim collar and pink bow. A large sunflower is pinned to his jacket. The Aesthetic Movement had specific ideas about the most beautiful flowers (sunflowers and calla lilies) and colours (purple and green). The design, first registered on 21 December 1881, references Gilbert and Sullivan’s operetta Patience, which features a poet called Bunthorne, a caricature of Oscar Wilde.

The teapot base is inscribed: FEARFUL CONSEQUENCES – THROUGH THE LAWS OF NATURAL SELECTION AND EVOLUTION OF LIVING UP TO ONE’S TEAPOT. Whilst a student at Oxford University Oscar Wilde once said, “I find it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue china”, which could be the reason for the reference. The inscription also mocks Charles Darwin’s newly introduced theory of natural selection, which was scoffed at by conservative, pious Victorians.

For Wilde, colour was an intense response to the visible world: “the undying beauty of things that fade and die”. In 1890 Wilde wrote in his essay, The Critic as Artist, that “even a colour-sense is more important in the development of the individual, than a sense of right and wrong”. Wilde’s downfall in his late career is a stark reminder that the Aesthetic Movement was not just pretty William Morris lattice-designed wallpapers and peacock-feather Liberty prints. It was risky. This was the era of the British Empire, Gladstone, and the sanctimonious bourgeoisie afraid of social change. In Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), the ‘hero’ exposes the decadent, dark side of Aestheticism in his quest for sensation and beauty without limits. The sheer audacity of Wilde defied the Victorian age until it finally destroyed him, convicting him in 1895 for homosexual ‘crimes’, degrading his health in Reading Gaol for two years, and then discarding him abroad: disgraced, despised and penniless.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, Aestheticism transformed the visual arts and literature, and ushered in a licence to provoke. However, the descent of the Aesthetic Movement into perceived perversion, decadence and effeminacy, was inevitable. Even Whistler denounced those “false prophets who brought the very name of the beautiful into disrepute”. But for me, Oscar Wilde will always be Beauty’s most convincing and articulate champion.

“Beauty is the symbol of symbols. Beauty reveals everything, because it expresses nothing. When it shows itself, it shows us the whole fiery-coloured world.” Oscar Wilde, 1890, The Critic as Artist.

The NGV exhibition, Whistler’s Mother, runs until 19 June and is accompanied by an excellent 88-page hard-cover publication.

Featured image: James Whistler, Variations in Blue and Green, ca 1867-68, Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington.