In 1848, inspired by medieval art and literature, seven young British artists formed the semi-secret Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB). Together they explored new ways of ensuring that visual truth could be better expressed through a more realistic, less idealised art, which had been previously defined by the standards of classicism and High Renaissance art. During a time of profound change in Britain, these artists wanted to make a difference by creating art that was more attuned to the naïve medieval style of the fifteenth century. The PRB was short-lived—it dissolved in 1853 and the seven ‘brothers’ went their own way.

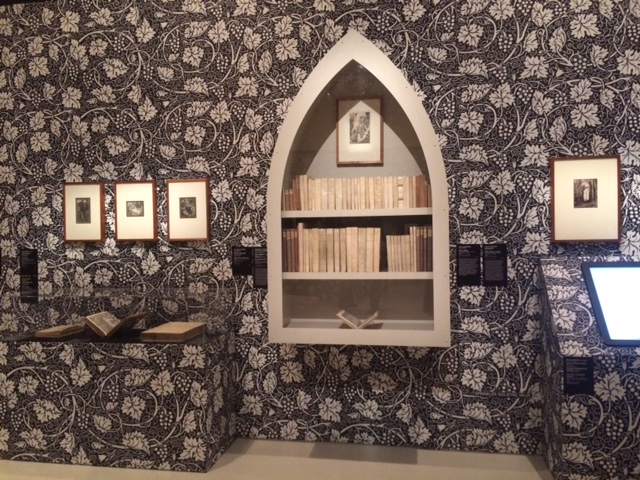

There’s a lot to like about Medieval Moderns: the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, an exhibition now showing until 12 July at the National Gallery of Victoria. The red walls in the first couple of rooms, with Gothic Revival arch-shaped doorways separating the four gallery spaces, evoke a medieval mood, and take the chill off this autumnal Melbourne weather. But does the exhibition deliver what it proposes: art by the PRB which proves they were ‘medieval moderns’?

If we consider the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in their purest period of youthful, unadulterated ‘all for one and one for all’ rebellion against the conventions of art taught at the Royal Academy of Art in London, this exhibition won’t satisfy: London has most of those early Pre-Raphaelite treasures dating from 1848 to 1853. I was lucky enough to see much of this early art in the exquisite 2012 Tate Britain exhibition, Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-gardes, which I have written about here.

I scan the first room for what the three wall labels promise: how the PRB evolved and the ideals of the founding members— William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti (writer), Frederic George Stephens, James Collinson and Thomas Woolner (sculptor). I spy a Woolner, a D.G.Rossetti, a Millais and a Holman Hunt. Even though these four works of art were all produced after 1853, they are fine examples of some of the tenets of Pre-Raphaelite art—and the way the young artists developed their own technique as a means of evoking their own interpretative expression.

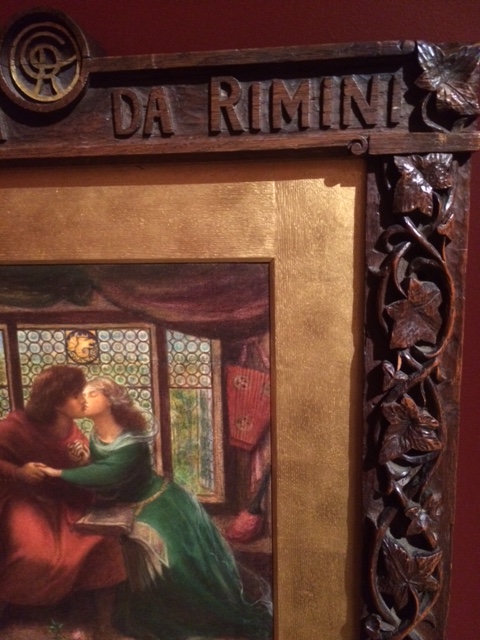

It’s worthwhile beginning with Dante Rossetti’s watercolour on paper, Paolo and Francesca da Rimini, painted in 1867. This is a snapshot of Pre-Raphaelite interest in medieval art and literature. There was a revival of interest in medieval history, art, literature, and gothic buildings in Victorian Britain (1837-1901) and the term, ‘medievalism’, was coined.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, ‘Paolo and Francesca da Rimini’, 1867, watercolour, gouache and gum arabic over pencil on 2 sheets of paper, 43.7 x 36.1 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Paolo and Francesca da Rimini depicts a moment of passion in the medieval tale of the forbidden love of Francesca da Rimini and her brother-in-law Paolo Malatesta. Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-82), with his Italian blood and intense passion for poetry, was particularly fascinated by stories taken from medieval European literature featuring ‘fallen women’, femme fatales and tragic lovers. The lovers in this painting kiss as they sit in a sun-lit alcove, ignoring the message in the book they have been reading about the adulterous love between the knight, Sir Lancelot, and King Arthur’s wife, Guinevere. Francesca was married to Paolo’s brother, Giovanni, who murdered them both when he found them in Francesca’s bedroom. The story relates to Dante Alighieri’s meeting of the doomed lovers as he passes through Hell in the first volume (Inferno) of the medieval Italian poet’s Divine Comedy. A translation of this Canto is inscribed on the lower edge of the finely carved frame, which references the beginnings of the Arts & Craft movement and the importance of craftsmanship in an increasingly mechanised world.

Rossetti sketched the work in pencil, before applying layers of watercolour and thick pigments of opaque gouache to create depth as well as a soft, dream-like effect. This build-up of pigments and layers of varnish on a white ground gave the early Pre-Raphaelite paintings a luminescence (we will see another example in the fourth room).

Thomas Malory’s fifteenth-century text Morte d’Arthur inspired Rossetti, and he produced designs for the illustrated edition of Tennyson’s Morte d’Arthur published by Edward Moxon in May 1857, of which there are some remarkable examples displayed in the third room. Rossetti was obsessed with the love triangle between King Arthur, Sir Lancelot and Queen Guinevere, which included passion and adultery, and ended in the ruin of Camelot. The male-dominated Victorian society maintained strict moral codes and gender roles and women were dependent on men to support them financially; the ‘fallen woman’ was unfairly dealt with. It was a time when the dominant ideal of womanhood was the pure ‘angel in the house’: wife, daughter, mother. Malory’s fatalistic vision that nobly conceived ideals cannot survive the failings of human nature was attractive to Pre-Raphaelite painters.

Across from Rossetti’s watercolour hangs John Everett Millais’ 1855 masterpiece, The rescue, which represents the PRB’s interest in capturing urban life and the heroics of ‘ordinary’ people. The painting depicts a strong, handsome fireman rescuing three young children from a house fire: a baby under his left arm, a girl under his right, and a boy clinging to his back—all being delivered into the arms of their anxious mother. The PRB looked for chivalry in a Victorian society consumed by the materialism of the nouveaux riche industrialists, the chivralic model of which was to be found in the ideal of the medieval knight. Even though the PRB had dissolved two years previously, in this painting Millais (1829-1896) shows his respect for Pre-Raphaelite naturalism and love of narrative; however, the painting has a depth and intensity in its chromatic modelling that was abhorred by the PRB. Many thought that Millais betrayed the PRB by becoming an associate of the Royal Academy in 1853 and returning to a darker tone in his paintings, hinting at his renewed interest in the Old Masters.

William Holman Hunt, ‘The Importunate Neighbour’, 1895, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), one of the original seven, produced works based on biblical narratives throughout his career.The Brotherhood aimed to make religious imagery more appealing and relevant to a contemporary audience. Influenced by the spiritual qualities of medieval art, the PRB opposed the alleged rationalism and idealised beauty of Renaissance religious art embodied by Raphael. Hunt often travelled to the Holy Land, and The Importunate Neighbour, hanging in the same exhibition space as the Rossetti and the Millais, is one of his late religious works (1895). This moody, dark painting lacks the typical high-keyed colours of Hunt’s work, but suits his chosen subject matter. Inspired by a story in Luke’s gospel [11: 5-10], Hunt visualises the moment when the importunate or persistent neighbour knocks on his neighbour’s door, late at night, asking for bread for an unexpected visitor. Hunt captures the moment of anguish when this request is refused. However, the man persists and eventually his neighbour provides him with food. The painting therefore illustrates the moral of the parable: ‘Ask, and it shall be given to you’. Of all the members of the PRB, Hunt remained the most committed to subject matter that maintained Pre-Raphaelite attention to detail and narrative.

The other work in the first room by another founder of the PRB is Thomas Woolner’s plaster sculpture, In Memoriam: Four Children in Paradise (1870), which embodies a poignant and realistic reminder of the vulnerability of children in Victorian England, and the high death rate. Woolner (1825-1892) left the Brotherhood in 1852 when he sailed to Australia to seek his fortune (unsuccessfully) in the Victorian gold rush. He returned to England two years later and prospered as a portrait sculptor.

Curatorial explanation on labels is sometimes short on adequate information, and critical visitors may be left scratching their heads. The label in the first room states: “Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s following included the two most influential associates of the Brotherhood, Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, who carried the group’s traditions well into the twentieth century.” Burne-Jones and Morris appeared on the scene after the disbandment of the PRB and were captivated by Rossetti. I don my editor’s hat and identify confusion in the wording: the label reads as if Burne-Jones and Morris “carried the group’s traditions well into the twentieth century”. Burne-Jones died in 1898 and Morris in 1896. How is the “group” defined? What are the “traditions”? I go searching for answers in the next room.

1857 marked the beginning of a period during which a group of artists was influenced by the so-called second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism embodied in the Rossetti circle, which included Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898), and William Morris (1834-1896). These artists, with Rossetti as their leader, were commissioned to paint murals on the walls of the Oxford University Debating Hall based on medieval Arthurian legends. Burne-Jones was also interested in interested in mythology, which extended to his choice of subject matter for his paintings, and the second room has two such paintings.

Burne-Jones’ late-career painting, Wheel of Fortune (begun in 1871 and not completed until 1885), with its Michelangelo-inspired bodies, and soft sfumato, seemingly copied from studies of paintings by the Venetian Renaissance artist, Giorgione (died 1510), is far-removed from Pre-Raphaelite ideals of early Italian art before 1500: flat, angular drawing style with a radiant palette. The wheel belongs to the goddess Fortuna, who turns her wheel to which three mortals are bound: at the top a slave rests his foot on the crowned head of a king below, in the centre the king wearing a crown and holding a sceptre and, below, a poet, on whose head rests a laurel wreath. The ever-changing positions of those on the wheel represent life’s capriciousness and the image was widely used as an allegory in medieval literature.

The aesthetic principles of the Pre-Raphaelites such as precision of focus, flattening of forms, and radical cropping of the visual field were taken up by some of the early photographers who wished to raise this new medium to an artistic level. Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) was a pioneering photographer influenced by Pre-Raphaelitism. One of Julia Cameron’s six sisters , Sarah Prinsep (mother of the painter Val Prinsep, a follower of Rossetti), held regular salons at her home in London: Little Holland House. These were attended by the Pre-Raphaelite painters including Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Burne-Jones, and literary luminaries of the day: Tennyson, Dickens, Darwin, G.F.Watts and Herschal (all photographed in Julia Margaret’s glasshouse).

Julia Margaret Cameron, ‘Julia Jackson’, 1864, Albumin Silver Photograph, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Hanging in the third room is this intimate photograph taken in 1864 by Cameron of her niece, Julia Jackson, who was the mother of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell. Cameron particularly admired D.G. Rossetti, and rejected the razor-sharp clarity of daguerreotypes, allowing softly modelled single heads to follow Rossetti’s more painterly style of the 1860s.

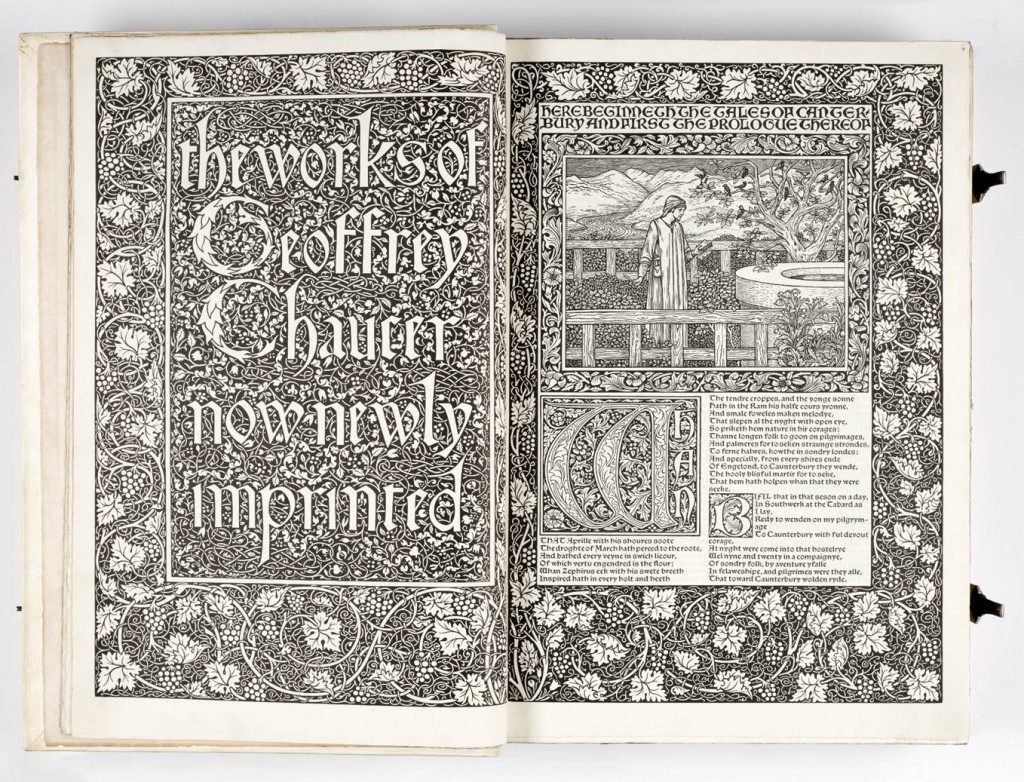

The last room of this exhibition is a tangled web of late-Victorian decorative arts, furnishings and furniture, with a display of printed editions of English classics from William Morris’ (Morris & Co) Kelmscott Press, including the Works of Geoffrey Chaucer (1890-96). Three interesting paintings featuring medieval ‘fallen women’ and a femme fatale by two followers of Rossetti, Valentine Prinsep (1838-1904) and Arthur Hughes (1832–1915) unfortunately hang on the walls which have been papered with an enlarged black and white design copied from the Morris design in the borders of a Kelmscott Press edition of Chaucer featured in the room (see image above). The paintings (ranging in dates between1854 ad 1865) return our thinking to Pre-Raphaelite medievalism and subject matter featuring ‘fallen women’. These three paintings would have looked sensational hung on the red walls in the first room, near Rossetti’s 1867 watercolour of Francesca and Paola.

The first painting is The flight of Jane Shore (c. 1865) by Valentine (Val) Cameron Prinsep and featuring a ‘fallen woman’: Elizabeth ‘Jane’ Shore (c.1445-1527), the legendary English medieval adulteress and royal mistress to King Edward IV (1442-1483). Prinsep was the quintessential Victorian man of considerable physicality, wealth and social standing. His critical reception as a young artist between the years 1857 and 1865 has been connected to his close association with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the circle of avant-garde artists that formed under Rossetti’s leadership following the dissolution of the original PRB. Prinsep wrote in his memoir: “Medievalism was our beau ideal and we sank our individuality in the strong personality of our adored Gabriel”.

Val Prinsep, ‘The flight of Jane Shore’, c. 1865, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Through his bohemian mother’s salons, Prinsep was in contact with a range of notable mid-nineteenth-century British writers, artists and social activists. The problematic socio-economic issue of the ‘fallen woman’ had a significant contemporary resonance for Victorians, and accordingly, ‘she’ featured regularly in art and literary texts. This dark painting depicts Jane Shore, the quintessential Pre-Raphaelite beauty, as a wide-eyed and frightened ‘fallen woman’ crouched against a wall in a ditch. Following the death of Edward, she was accused of witchery and harlotry by Richard, Edward’s brother, and cast out from the royal court. Night is falling and the twilight (or is it dawn?) adds drama to the scene. A procession of medieval soldiers on horseback led by Richard ride along the embankment; the Tower of London is outlined against the sky as this was to be the final destination of the two young princes, seen riding behind Richard (soon to be Richard III).

Arthur Hughes, ‘Fair Rosamund’, 1854, oil on wood panel, 40.3 x 30.5 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Another follower of Rossetti, and a mate of Prinsep, was Arthur Hughes; two of his paintings are hanging in this last room alongside Prinsep’s Jane Shore. Hughes and Prinsep were included in the Rossetti circle during the1857 Oxford mural-painting campaign. Hughes’ painting, Fair Rosamund (1854), is a perfect example of the Pre-Raphaelite technique of painting onto a white ground on fine-weave canvas, which produced the brilliant iridescent colour effects the early Pre-Raphaelites desired. The PRB rejected the traditional method of ‘dead-colouring’, or underpainting in earth tones to establish light and shadow. Instead, early Pre-Raphaelite paintings, like this, recreated in paint the glassy luminosity of sharp photographic images.

Rosamund Clifford (‘Fair Rosamund’ c.1133-c.1176), was mistress to King Henry II (1133-1189). To protect her, Henry had a maze constructed at Woodstock Park, his royal refuge, and no-one knew the clue to the labyrinth during their decade-long affair. According to stories of Rosamund’s life, Henry’s jealous wife, Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine hunted out Rosamund in her hidden chamber and forced her to drink poison. Arthur Hughes has painted Rosamund as a full-length figure standing inside a flowering walled garden. She looks naïve, as Eleanor stands menacingly in the background. As subject matter, Rosamund Clifford and Jane Shore were popular amongst Victorian artists and writers nostalgic in their references to the age of medieval chivalry and perhaps a growing contemporary demand for women’s education and emancipation.

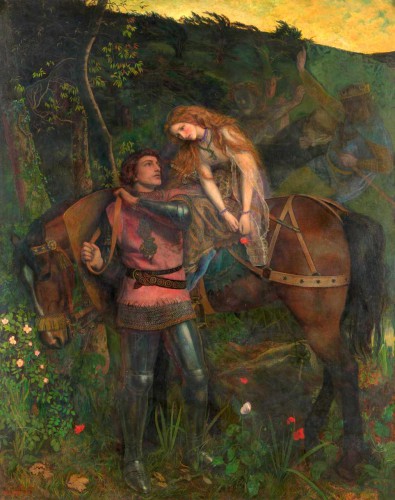

Close by hangs Hughes’ later, larger (featured) painting, La Belle Dame sans Merci (1863; oil on canvas), which not only relates to Pre-Raphaelite interest in Arthurian legends but also to Keats’ poems, and the rise of the femme fatale in nineteenth-century art and literature. The femme fatale lured men to their doom through her beauty, enchantments and sexual power. Keats’ ‘word-picture’ poem of the same name (1820) incorporated a romantic narrative of a knight’s enthralment by a ‘faery child’. Hughes has captured the moment when the knight is unaware of his impending doom: condemned to wander forever, lost in the world. This painting is similar in style to Prinsep’s Jane Shore.

The Rossetti brothers’ sister, Christina, lamented the demise of the PRB after five short years in her sonnet called ‘The P.R.B.’, which she wrote in November 1853:

The P.R.B. is in its decadence;

For Woolner in Australia cooks his chops,

And Hunt is yearning for the land of Cheops [Egypt];

D.G. Rossetti shuns the vulgar optic;

While William M. Rossetti merely lops

His B’s in English disesteemed as Coptic;

Calm Stephens in the twilight smokes his pipe,

But long the dawning of his public day;

And he at last the champion great Millais,

Attaining Academic opulence,

Winds up his signature with A.R.A.

So rivers merge in the perpetual sea;

So luscious fruit must fall when over-ripe;

And so the consummated P.R.B.

There is humour in Christina Rossetti’s observations: the image of Woolner in Australia ‘cook[ing] his chops’ and Hunt’s ‘yearning for the land of Cheops [Egypt]’. There is also an undertone of disapproval of Millais who becomes an associate of the Royal Academy, despised by the PRB: ‘the champion, great Millais’ who now ‘Winds up his signature with A.R.A.’, the initials suggesting his rejection of the ‘P.R.B.’ However, there is a sad and philosophical resignation that youth and new ideas will inevitably lose their ‘bite’ as time passes and age wearies the energy of youth.

Although the PRB split after five years, the spirit of these young artists, who not only rebelled against the conventions of Royal Academy tradition, but also against social and political inequalities, burned brightly throughout the Victorian era and beyond. They encouraged a new way of thinking about art, which didn’t necessarily result in a legacy of a specific ‘tradition’. Medieval Moderns: the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood applies a broad brush to this revolution, and most visitors would come away from this exhibition with a desire to know more about those avant-garde Pre-Raphaelites and their followers, who attempted to embrace the essence of the Middle Ages.