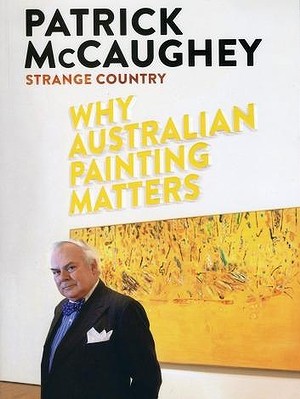

As ever, additional reading is high on my agenda of things to ‘do’ in the first few weeks of January. I’m not a book reviewer, but I can’t resist sharing my reading experience of Patrick McCaughey’s new book on Australian painting: ‘Strange Country: Why Australian painting matters’. I am a self-confessed painting-aholic so this book is fodder for my addiction: a first-rate example of how art history can be written—by an eminent art historian—in a way which is appealing to a cross-section of readers. In other words, this book passes my readability test: the content delves into art historical research, but delivers it with enlightening flourishes and an uncanny journalistic flair. I am reminded at times of Robert Hughes’ opinionated views and acerbic wit. I bought this book before Christmas, wrapped it, and put it under our Christmas tree—for me! My summer reading has been a joy so far . . .

Patrick McCaughey is a much-respected art critic and academic: between 1974 and 1981 he was professor of visual arts at Monash University, and the director of the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne from 1981 to 1987; then he moved to the United States where he was director of the Wadsworth Athenaeum, the chair of Australian Studies at Harvard and director of the Yale Centre for British Art (take a breath!). At the age of 72 he has published Strange Country: Why Australian painting matters through Melbourne University Press (MUP).

‘My soul,’ he whispered,

Over the sea-surge,

‘My soul is a strange country.’

(Randolph Stow, To the Islands, 1958)

It’s obvious: Patrick McCaughey is hooked on Australian painting, and he seduces me when he writes with so much passion and vision about the paintings and the artists he admires the most; for example, Hugh Ramsay’s evocative painting, The Sisters (1904), which the young artist painted virtually from his death-bed.

Warned about overworking, Ramsay painted on regardless and produced a final masterpiece of his sisters, Madge and Nelly. In this work Ramsay adopts the panoply of Sargentesque social portraiture and concentrates on the silver and gold ‘arrangement’ of the shimmering dresses. The compression of the composition, the closeness of the sitters to artist, breeds an airless claustrophobia. The alternating alertness and ennui of the sisters, bored by having to dress up in evening gowns in the middle of the day and pose in the over-heated studio, adds to the ambivalence of the painting. Far from being an essay in the feminine, the dying painter/brother is under the scrutiny of his sisters, even as they fall under his gaze. A suffocating pall hangs over the work.

McCaughey includes those ‘big’ names in Australian art that have been discussed and written about over and over again by art historians. Some will be critical of this; but, there is no doubt that he describes well-known paintings with new insights and intelligent perceptions.

Strange Country commences with a prologue called ‘Circa 1960’ in which he argues that the “origins of the art world of the twenty-first century lie in the renewal of Australian art circa 1960”. Chapter One, ‘In the Beginning’, is a summary of the modern Aboriginal art movement post-1970—which fuels the fire as to whether there should be a separation of indigenous and non-indigenous art in museums and art history books.

Then he moves into a broad survey of colonial painting, covering the three major ‘colonial’ artists: Glover, von Guerard and Buvelot—and these three are certainly interesting, having produced a heap of paintings that captured “the wild and the settled” Australian landscape through the eyes of European painters. How can you not be charmed by McCaughey’s admiration of Eugene von Guerard’s extraordinary talent?

The new world, and its untrodden wildness, unleashed in him a pictorial power, a feel for the sublime without rhetoric, hitherto unknown in Australian art and unmatched until the mid-twentieth century.

The next three chapters cover Australian Impressionism and McCaughey’s account of the Heidelberg School. Here is another contentious issue: many art historians reject this narrow categorisation of late nineteenth-century Australian artists, which include Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton, who were also labelled, ‘Impressionists’. In 2007, art critic Robert Nelson commented that the best collective name for this ‘movement’ would be the Australian Aesthetic Movement: “The relationship with Impressionism invokes too many negatives and misses the attenuated sonorities that characterise these delicate moody pictures.”

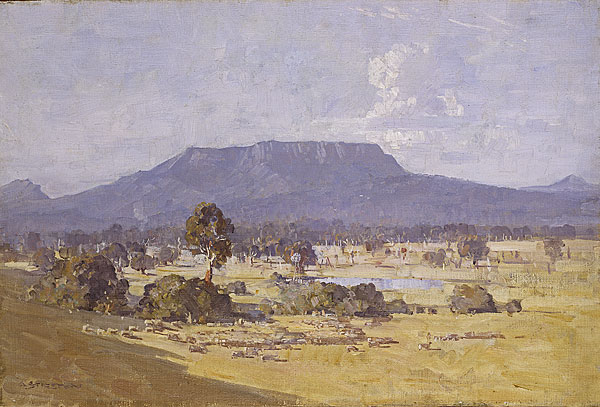

Perhaps my favourite chapter is ‘The New Woman and the Old Men’ because McCaughey expands his focus to embrace and celebrate, in detail, the art of another magnificent trio—the female Australian Modernists who were active between WWI and WWII: Grace Cossington Smith, Clarice Beckett and Margaret Preston. McCaughey comments, quite rightly, that these women “would come to be seen as the major artists of the period, and would marginalise the work of the Old Men. Hall and Lambert are now period curiosities.” A few pages earlier, McCaughey described Bernard Hall’s long tenure at the National Gallery of Victoria (1892-1935) as casting “a pall over Melbourne”. His explanation is limited, probably for obvious reasons. Rupert Bunny’s name is missing from the index, so one can assume he doesn’t rate with McCaughey either. And according to McCaughey, Arthur Streeton (1867-1943) in his later years was the “embodiment of the Melbourne establishment between the wars and spread his conservative views as art critic for The Argus.” Regarding Streeton’s 1926 painting, The Land of the Golden Fleece, McCaughey wrote: “From grazing sheep to the blue Grampians in the background, Streeton managed to get every cliché of Australian pastoralism into a single work.”

Arthur Streeton, ‘The Land of the Golden Fleece’, 1926, oil on canvas, 50.7 x 75.5 cm, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Yes, McCaughey has his favourites, and he champions Sidney Nolan, Russell Drysdale and Fred Williams as the giants of Australian painting. Of Nolan he wrote:

In Nolan’s hands the Australian landscape becomes a place of trial, the ultimate theatre of the struggle to survive. Could he have demonstrated why Australian painting matters more clearly?

And you can ‘feel’ McCaughey’s affection and respect for his friend, the Melbourne-based artist Jan Senbergs (four years older than McCaughey). He describes Senbergs’ expressionist “axle-grease” period during the 1960s and his marvellous twenty-first century Melbourne ‘maps’, which celebrate the landmarks and urban energy of Melbourne.

Strange Country concludes with a glance at Australian contemporary art and benign references to the “social and political agenda” of contemporary content through new media, which he believes has “begun to produce such repetitive work with an in-built, ephemeral quality to it”. He is confident of the ability of Australian painting to survive. It is McCaughey’s belief that the “revived and strengthened scene in contemporary painting is largely, but not exclusively, the work of women artists”, such as Sally Gabori’s abstract paintings of her country and Kristin Headlam’s series of paintings of her Brunswick garden—“Place here is identity”.

Sally Gabori, ‘My Country’, 2009, oil on canvas and linen, 151 x 101 cm, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

I know I will constantly refer to this book, reminding myself that Australian painting really does matter to Australians who have a strong sense of self and place. It is also McCaughey’s hope that Australian art will be understood and appreciated to a greater extent overseas (remember the general disdain for Australian art on display at the Royal Academy’s 2013 Australia exhibition in London?). McCaughey’s epilogue is inspiring:

. . . like W. H. Auden’s great insight into the nature of poetry—“it exists in the valley of its saying” —so painting exists in the valley of its being, its present-ness, its radiance as an object on the wall before us. Its authenticity derives from the artist’s truthfulness to experience and the originality of their inspiration.

Strange Country suits me in every way. It’s in paperback form and a reasonable size for a book on art (it fits snugly into my ‘train bag’), if a trifle heavy. But the choice of paintings as illustrations, and the quality of the reproductions regardless of the size, is one of the book’s greatest assets.

McCaughey has dedicated this book to his partner Donna Curran, who runs “the best restaurant in Connecticut”. They live on the banks of the Quinnipiac River in an oysterman’s house where McCaughey spends much of his time writing. The last oysterman has his wharf next door. What a way to spend one’s twilight years.