Australian artist Jenny Watson believes that painting should be as natural as breathing. Without doubt her paintings convey an honesty and directness that can only be achieved if the subject is personal. For four decades Watson has painted images of herself in various places at home and overseas: an isolated female with penetrating eyes and long, flowing hair that ranges in colour from blonde through to orange and red. She is often in the company of a cat or a horse. Watson has said on many occasions that her art is mainly autobiographical and demands a response from the viewer.

Born in Melbourne in 1951 Jenny Watson left her homeland in 1975 for the more creative fields of Europe. This was a time when young Australians travelled (escaped) and worked abroad, freed from the burdens of distance and provincialism. Consequently, Watson has developed a stylistic hybridity in her art that is grounded in punk and conceptual art. Her paintings embody narrative fragments of her life on the road and at home in Australia: nostalgic and imaginative, feminist and political, yet always personal. In the 1980s Watson abandoned the precision of her painting style and moved into her faux-naivety style. Although Watson’s paintings appear flat, they are alive with meaning, colour and movement; the passing of time and sense of place across many countries are keenly evoked.

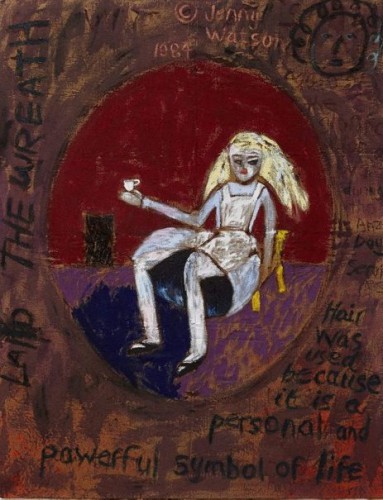

The featured image, Alice in Tokyo (1984, oil, synthetic polymer paint, ink and horse hair on hessian, © Jenny Watson, The Art Gallery of NSW), references Lewis Carroll’s Alice who fell down a rabbit hole into Wonderland and found herself alone in an alien land with strange characters. Alice’s outsider status is magnified by being out of proportion with her surroundings: she is either too large or too small. Watson recalls the same feeling when she visited Tokyo for the first time and found herself sitting in a café with furniture that made her look out of scale. Her sense of dislocation and estrangement in a foreign country are expressed through fantasy, but her use of everyday non-art materials such as hessian and horse hair suggest that she demands connection with the real world.

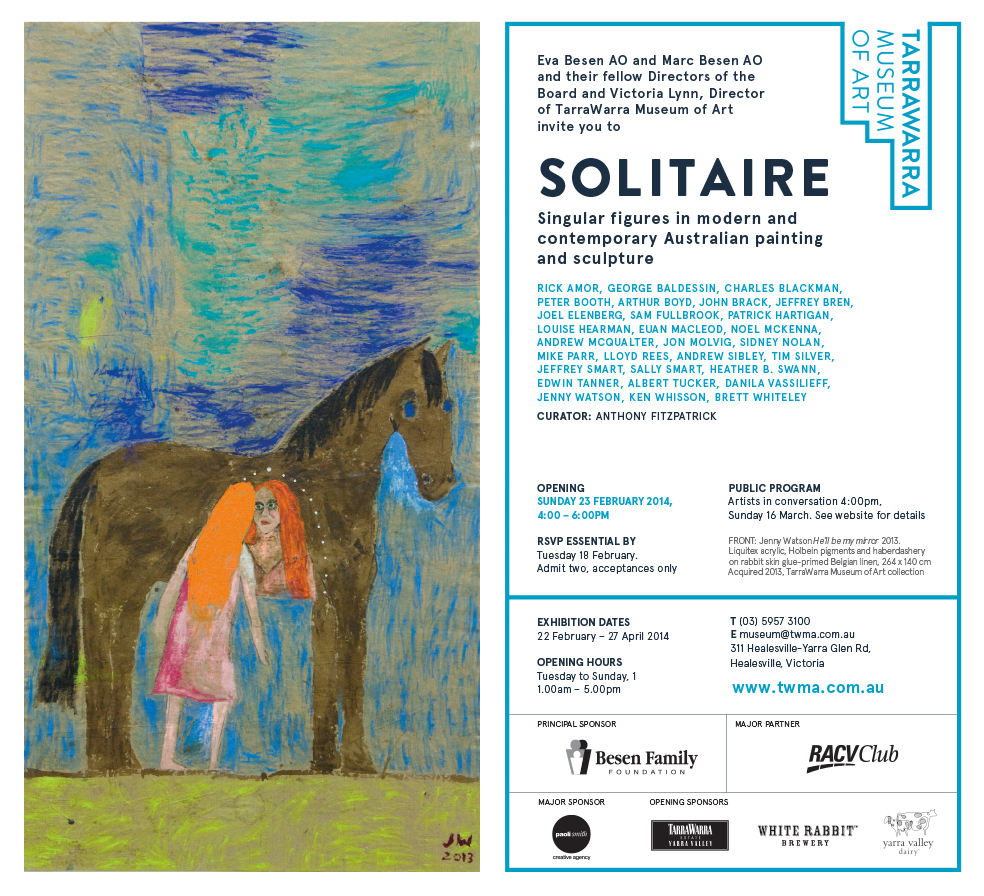

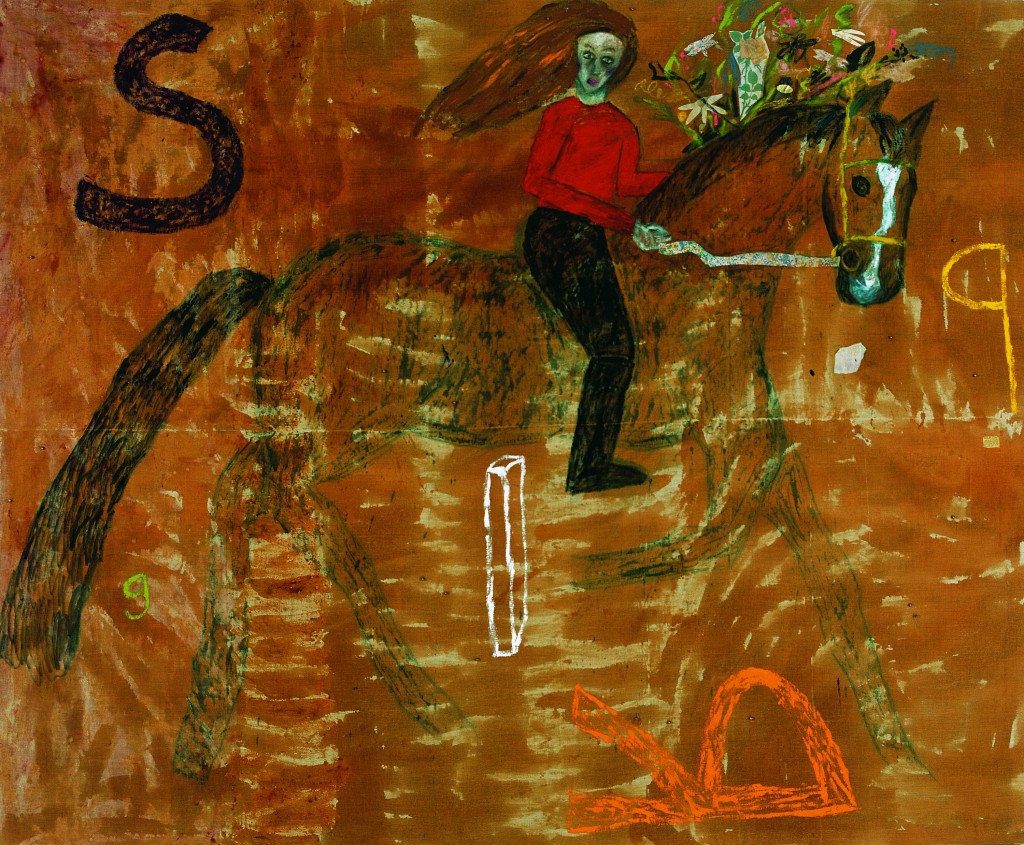

Jenny Watson, ‘Spring’, 1989, oil, collage, beads, rabbit skin glue and material on canvas, 204.9 x 250.2 cm, Gift of Eva Besen AO and Marc Besen AO 2003, TarraWarra Museum of Art collection.

A love of horses has been a constant for Watson since childhood and her paintings that depict her alter ego alone with her horse are endearing, conveying a sense of seclusion yet connection and freedom. Spring (1989), which I viewed recently at the TarraWarra Museum of Art (TWMA) in Healesville, is a perfect example. The current exhibition, Solitaire, is running until 27 April and features singular figures in modern and contemporary Australian painting and sculpture. Standing close to this large painting reveals gestural brushstrokes across textured fabric that has been fixed to the canvas with rabbit glue. The exhibition catalogue describes the girl and her horse as being “fused together, the flowing hair of the girl directly echoing the horse’s long black tail, as they stride rapidly and freely through a backdrop of broad horizontal brushstrokes which accentuate the lightness and speed of their movement . . . suggest[ing] a fleeting, dreamlike memory from childhood when solitude meant the potential for innocent abandon, the release of unbridled energy, and the possibility of escape”.

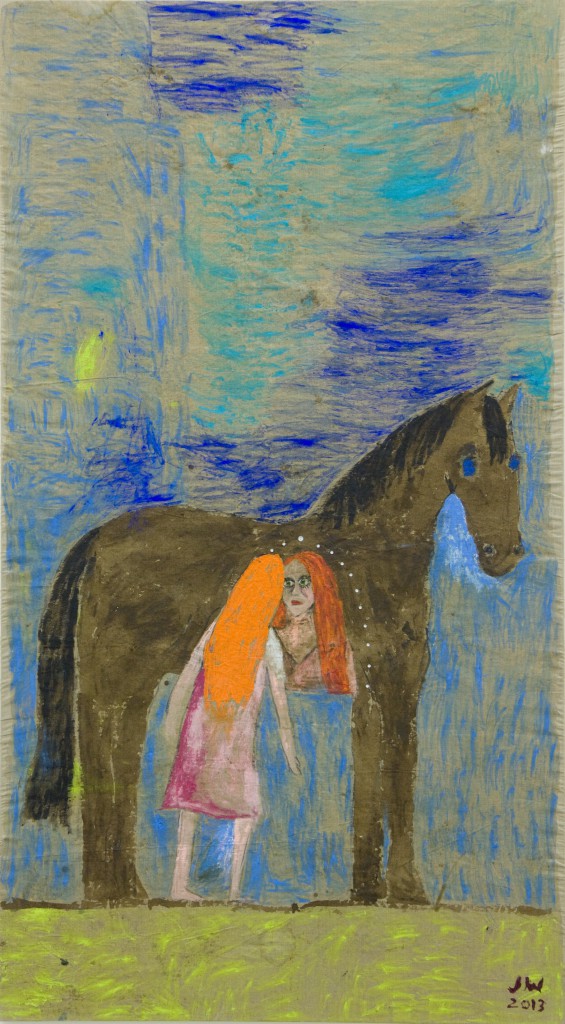

Jenny Watson, ‘He’ll be my mirror’, 2013, liquitex acrylic, Holbein pigments and haberdashery on rabbit skin glue-primed Belgian linen, 264 x140 cm,TarraWarra Museum of Art collection.

The joie de vie conveyed in Spring is infectious; 24 years later, at the age of 62, Watson painted a self-reflective painting, He’ll be my mirror (2013). In solitude, the orange-haired woman uses her ‘rock solid’, loyal horse as a mirror to scrutinise herself. Self-inspection in a mirror takes place on a daily basis for most people, but as one grows older, looking at oneself in the mirror often becomes a critical examination of the inner self and an assessment of one’s life. The intensity of the woman’s introspective looking is mirrored by the horse’s fixed gaze into the distance, seemingly on the lookout for any potential invasion of her privacy. This painting can be seen within a wider context in which artists have examined their identity through self-portraits for centuries; self-portraiture using a mirror remains a compelling contemporary method of self-examination.

Watson’s ‘home and away’ journey began as a Pop-punk artist living in Melbourne in the 1970s (and associating with Rock artist Nick Cave and his band, The Boys Next Door), seeking to establish her difference from the mainstream. Even though Watson has achieved international fame since, she has remained grounded and unselfconsciously herself. Jenny Watson is currently living with her partner in Brisbane, painting and teaching, and spending time with her three beloved horses—no longer alone, or struggling to make her way in foreign places.

The curator of Solitaire, Anthony Fitzpatrick, has chosen a broad range of paintings and sculptures by Australian artists, such as Rick Amor, Heather B. Swann and Sidney Nolan, to depict solitary figures. The grouping of these works is clever, and aesthetically pleasing.

“Drawing predominantly from the TarraWarra Museum of Art collection with selected loans, this exhibition explores various perspectives on solitude . . . Represented in manifold guises and divergent contexts, the isolated figure recurs throughout Solitaire, reflecting a range of perspectives on the nature of aloneness and the multiple states of being which it can engender.” Anthony Fitzpatrick, Solitaire catalogue.