Through the swift application of paint, the French Impressionist artists aimed to capture the atmosphere of a place at a specific time of day. When I read the first few paragraphs of a novel, or an unpublished manuscript set in a fictional place that is sent to me for assessment, I want to be captivated by a sense of place. This begins the transportation of readers into an imaginary world. Even though they know it is a fictional story, the place they are being introduced to has to convince them that it’s real. Launching into a scene without establishing the place in which it is set will fail to provide an anchor and backdrop to the action.

The opening paragraph of Pip Williams’ ‘The Dictionary of Lost Words’ (2020) is simple, but there is an immediate sense of place:

Scriptorium. It sounds as if it might have been a grand building, where the lightest footstep would echo between marble floor and gilded dome. But it was just a shed, in the back garden of a house in Oxford.

Readers will immediately start imagining who inhabits the Scriptorium before the first character is introduced.

The first page of Charles Dickens’ ‘Great Expectations’ (1861) delivers a more descriptive and immersive evocation of place. Pip, the protagonist and narrator, tells us:

Ours was the marsh country, down by the river, within, as the river wound, twenty miles of the sea … the dark flat wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with dykes and mounds and gates … the low leaden line beyond the river … the distant savage lair from which the wind was rushing, was the sea …

The alliteration in low, leaden line combines with words such as dark, flat, distant, savage to evoke a sense of desolation, isolation, and primordial savagery that is sure to inculcate many of the characters. By choosing to tell the story using the first-person point of view, we see Pip’s menacing childhood landscape through his eyes, which makes it seem even more realistic and chilling.

In contrast, George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) describes a more romantic, gentle place in the first long paragraph, which comprises the first page, of ‘The Mill on the Floss’ (1860):

A wide plain, where the broadening Floss hurries on between its green banks to the sea, and the loving tide, rushing to meet it, checks its passage with an impetuous embrace … It seems to me like a living companion while I wander along the bank and listen to its low, placid voice …

Dickens and Eliot have given the reader a broad bird’s-eye view of a specific place that will affect the characters’ lives. In many ways, these places are characters themselves, one gentle and nurturing, and the other, threatening and savage.

Geraldine Brooks writes a strong opening in her masterful novel, ‘Year of Wonders’ (2002). The first part of the story is set during ‘Leaf-Fall, 1666’, and Chapter 1 is titled ‘Apple-picking Time’. Anna, the young narrator describes the scene before her:

I used to love this season. The wood stacked by the door, the tang of its sap still speaking of forest. The hay made, all golden in the low afternoon light. The rumble of the apples tumbling into the cellar bins. . . thick, sweet scents of rotting apple and wet wood.

A sense of place comes alive when the right sensory details allow the reader to hear the apples tumbling into bins; to smell the sap, the rotting apples and the wet wood; and to see the golden autumn light as the sun slips towards the horizon. Due to Brooks’ evocative writing, our senses are on high alert, and these autumnal sights, sounds and smells cleverly foreshadow tragedy, decay and death. For Anna, her English village is far more than just a physical space to be inhabited; it is something that she interacts with on a deep emotional level. At the end of the novel, Anna chooses to leave England and make a new life for herself and her daughters. She sails to the Middle East, far-removed from the dark, dank place of slow-death that was her home, to an exotic country exploding with life, light, heat, spices and colour.

And then one morning I awoke to a smooth sea and warm air spiced with cardamom. I gathered up the baby and went on deck. I will never forget the dazzle of the sunlight, glinting off the white walls and the golden domes, or the way the city spilled down the mountain and embraced its wide blue harbour.

The opening lines of the novel ‘Chocolat’ (1999), written by Joanne Harris, transport readers into a French village alongside its two new occupants, Vianne Rocher and her six-year-old daughter, Anouk. All of the senses are on alert: smell, taste, touch, sound and sight:

We came on the wind of the carnival. A warm wind for February, laden with the hot greasy scents of frying pancakes and sausage and powdery-sweet waffles cooked on the hotplate right there by the roadside, with the confetti sleeting down collars and cuffs and rolling in the gutters like an idiot antidote to winter.

World-building doesn’t just stop once a place is first introduced. The ‘where’ of it all must be seamlessly woven throughout the narrative, supporting the plot and action of the characters. Keep using the same setting, room or landscape to add depth to subsequent scenes. For example, if the story opens with a group of men meeting in a dimly lit room at the back of a barber’s shop, a close description of the room will enable readers to familiarise themselves with its layout and furniture. Next time the men meet, there could be someone lurking in the shadows behind a dark cabinet.

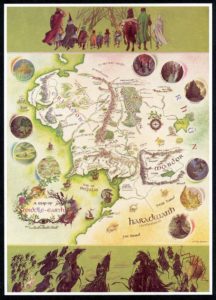

A while ago I assessed a Young Adult manuscript written by a talented emerging writer and I was impressed with the action-packed, outer-space science fiction/fantasy thriller with a headstrong heroine setting the pace. Even though it’s important to allow readers to imagine the settings of these fantastical places, I suggested that there could have been more attention given to describing the ‘landscape’ by ‘widening the lens’ and allowing readers to take in the inter-galactic world with its deep space and cosmic wonders. By doing this, readers would be able to orient themselves in the action through a sense of place that the characters inhabit. I also suggested creating a space picture-map that designated the fictional planets and cities. In my younger days, I spent many hours poring over an illustrated picture-map of Tolkien’s ‘Middle-earth’, picking out magical places such as Gondor, Rivendell and Isengard.

A writer recently admitted that she was afraid to burden her story with too much descriptive detail of places as she’d read too many Henry James novels and had been ‘put off’ by the extensive ‘mind-numbing’ detail. After some encouragement, she began to add more detail about the places in which the characters lived and interacted. This added a much-needed third dimension to the action. But keep in mind that readers can get bored with too much detail. They want atmosphere, mood and vivid language.

Whether the narrative is fictional or a memoir, the setting can be used to good effect in reflecting a character’s personality traits, state-of-mind and physical features. Describing a room in which the scene is enacted adds mood and drama. Grey walls, tattered curtains and unwashed dishes may reflect the predicament of the protagonist. In Dickens’ ‘Bleak House’ (1852-53), there are many broken-down interiors that reflect the mental and physical state of the characters. The Jellyby household is “nothing but bills, dirt, waste, noise, tumbles downstairs, confusion, and wretchedness”. The “dusty bundles of papers” in Richard Carstone’s room seems to Esther “like dusty mirrors reflecting his own mind”. Readers’ senses are alerted, and there is a greater understanding of characters through the evocation of the place they inhabit.

Evoking a strong sense of place through carefully crafted images will immerse readers into another world that directly influences how the characters live, develop a sense of identity, and respond to others.

Manuscript Assessment

If you are seeking an assessment of your writing project, whether it is a complete manuscript or a work-in-progress, I would be delighted to ‘hear’ from you. You can find more information, and my assessment process and fees, here.

I look forward to you sending me a message via my contact page or directly to denise@denisemtaylor.com.au with a brief overview of your narrative and I will respond within 24 hours.

Featured painting (top of page): Gustave Caillebotte, Boulevard des Italiens, 1880, private collection