Life is precarious — even more so since COVID-19 infiltrated our lives a year ago and we’ve had to learn to live with daily uncertainties. But compared with other countries, Australia is perhaps ‘luckier’ than most (I think of Donald Horne’s 1964 book ‘The Lucky Country’). So, although I do feel ‘lucky’, I am a Melburnian who is suffering withdrawal symptoms from being unable to travel north (and I don’t mean to Queensland) or west (and I don’t mean to Perth). I want to travel to distant places, feel safe, and walk freely at night . . .

“I want to be able to sleep in an open field, to travel west, to walk freely at night.” (Sylvia Plath, 1932 – 1964)

I frequently encourage fiction writers to look more closely at the setting/place of their narratives. One of the best ways to learn how to bring the setting alive is to read diary entries written centuries ago by travellers across Europe and by late-twentieth-century travellers to distant, often hostile places, such as British travel writer, Bruce Chatwin, who travelled to Patagonia (‘In Patagonia’, 1977) and Australia (‘The Songlines’, 1987). Travel literature is not easily defined or classified as it crosses a multitude of genres; personal responses to the natural environment and historic architecture always fascinate. But relating ‘otherness’ can be a slippery slope for many travel writers.

Today, the traditional travel writing genre could be collapsing as the world faces more and more polemic realities such as pandemics, over-population, climate change, racism, terrorism, and nuclear proliferation. We are more interconnected, and exotic places tend to be of the past. Many more voices will be heard, such as the voice of travel writer African American, Eddy L. Harris, who wrote ‘Native Stranger: A Black American’s Journey into the Heart of Africa’ (1992). Harris goes to Africa on a pilgrimage of sorts, not to regain his heritage, but to see what he has lost. He travels rough, and ‘light’. We ‘see’ modern Africa and that loss, but there is more to this book than racial exploration and survival.

In this article I have compiled a few diary entries and letter snippets that I included in earlier articles. They may be of interest as a way of ‘escaping’ during this global pandemic. I have chosen Mary Wollstonecraft’s raw experience of Scandinavia’s summer in 1796; Lord Byron’s brazen homage to the grandeur of Rome’s Pantheon in the early nineteenth century; Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s sensitive accounts of the lives of Turkish women in the early eighteenth century; and Hester Piozzi’s escape from stuffy British society to Italy in 1789. I finish with Bruce Chatwin’s impression of Australia’s interior and Indigenous Australians’ connections to their ancestral country. Having visited all of these places, I hope to return one day . . .

Joseph Brown (engraver, active between 1833 and 1886), probably adapted this engraving from the Spencer miniature of Lady Mary, for the edition of ‘The Letters of Horace Walpole (1717-1797)’, Noel Memorial Library, Louisiana State University, Shreveport.

“I am now got into a new world” wrote Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689 – 1762) in a lengthy letter to an unknown English woman. It was written from Andrianople (now Edirne, on Turkey’s border with Bulgaria) on 1 April 1717. Lady Mary was an avid letter writer and her direct observations of Ottoman culture supported her status as an authoritative commentator as she travelled from England through Eastern Europe to Constantinople (Istanbul) with her husband, Edward, the British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, and their three-year old son.

There are times when Lady Mary reveals her Eurocentric attitudes and English aristocratic snobbery; however, most of the time she was a sympathetic and sensitive traveller. She was the first European woman to document in vivid detail, and with comparative accuracy, the daily activities and customs of Muslim women, including the sacrosanct time that women spent in the Turkish hammam or bagnio (communal bathing house): “. . . ‘tis no less than death for a man to be found in one of these places”. Lady Mary’s intimate eye-witness account of a hammam begins with:

. . . I went to the bagnio about ten o’clock. It was already full of women. It is built of stone in the shape of a dome, with no windows but in the roof, which gives light enough. There were five of these domes joined together, the outmost being less than the rest, and serving only as a hall, where the portress stood at the door. Ladies of quality generally give this woman the value of a crown or ten shillings and I did not forget that ceremony. The next room is a very large one paved with marble, and all round it raised two sofas of marble one above another. There were four fountains of cold water in this room, falling first into marble basins, and then running on the floor in little channels made for that purpose, which carried the streams into the next room, something less than this, with the same sort of marble sofas, but so hot with steams of sulphur proceeding from the baths joining to it, ‘twas impossible to stay there with one’s clothes on. The two other domes were the hot baths, one of which had cocks of cold water turning into it to temper it to what degree of warmth the bathers have a mind to.

. . . The first sofas were covered with cushions and rich carpets, on which sat the ladies, and on the second their slaves behind them, but without any distinction of rank by their dress, all being in the state of nature, that is, in plain English, stark naked, without any beauty or defect concealed. Yet there was not the least wanton smile or immodest gesture amongst them. They walked and moved with the same majestic grace which Milton describes of our general mother. There were many amongst them as exactly proportioned as ever any goddess was drawn by the pencil of Guido or Titian, and most of their skins shiningly white, only adorned by their beautiful hair divided into many tresses, hanging on their shoulders, braided either with pearl or ribbon, perfectly representing the figures of the Graces.

Lady Mary sees these women through the lens of art, mythology and Western classical culture: the three Graces (Greek goddesses), and Eve (“our general mother”). She mentions Italian artists, Guido Reni (1575 – 1642) and Titian (c. 1490 – 1576), who both used colour and oil paint to create sensuous portraits of women in various poses. Even though Lady Mary glosses over the shadowy suffering and immobility that often afflicted those Turkish women of less privileged circumstances, and has been criticised for using sentimental and aesthetic language, her reporting notes cultural differences without overlaying them with moral judgements.

Beginning in the late-sixteenth century and through to the mid-nineteenth century, British aristocrats, Germans, Scandinavians, and also Americans, travelled to Paris, Venice, Florence, Naples and Rome to experience first-hand the art and culture of France and Italy on the Grand Tour. Travel was arduous as most travelled over the Alps in a sedan chair to experience the beauty and sublimity of nature. It was mainly young men with means who partook of the Grand Tour, however, towards the end of the eighteenth century, British women began to seek the same adventure abroad.

Hester Thrale Piozzi, 1785-1786, unknown Italian artist, oil on canvas, National Portrait Gallery, London.

In 1789, English literary figure, Hester Thrale Piozzi (1741 – 1821) lived in the small Italian community of Lucca (between Pisa and Florence) with her Italian husband, Gabriel Piozzi. Hester Piozzi’s acclaimed journal, Observations and Reflections made in the Course of a Journey through France, Italy, and Germany, often mocked the British. In London, as Hester Thrale (her first husband was the wealthy English brewer, Henry Thrale), she had been embraced by the upper middle class literary ‘blue-stocking circle’ of women (‘blue-stocking’ refers to the dress of the men who were included in the celebrated salon, such as Samuel Johnson) who engaged in rational conversation and encouraged individual opinion. However, social exclusivity and snobbishness were inherent in her circles, and when Hester flouted convention by marrying an Italian Roman Catholic musician in 1784, at the age of forty-three, she was excluded. But she embraced the exhilaration of traversing the Alps and crossing into Italy: “every step gives a new impression to the mind . . . while the portion of terror excited either by real or fancied dangers in the way, is just sufficient to mingle with pleasure . . . makes one feel the full effect of sublimity”. The new sensory association with the dramatic and primitive features of more wild terrain owed much to the writings of Edmund Burke’s Inquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Beautiful and the Sublime (1756).

It is understandable that Hester sought a considerable degree of emotional as well as intellectual freedom that had been denied to her by the constraints of London. She referred to Lucca, which was passed over in most Grand Tour itineraries, as “this fairy commonwealth”, where “liberty is written up on every wall and door”. Her informal and eccentric style of writing enhances the foreign content, such as when she describes the colourful mode of dressing for church at Lucca: “the church at noon looked like a flower-garden, so gaily adorned were the priests.” Here, she emphasises difference from home, supporting her acceptance of variety.

Nearly ten years ago, during the northern summer of 2011, I drove past mile after mile of Scandinavian forest and roadside wildflowers. Silver birches grow wild in harmony with aspen, blanketed together under snow during the winter months. Mary Wollstonecraft (of ‘A Vindication of the Rights of Women’ fame, 1792) was intoxicated by this place when she travelled around Norway and Sweden in the summer of 1796, which she described in a letter as short, it is true; but ‘passing sweet’ (probably gleaned from William Cowper’s 1782 poem, Retirement, 1.737: ‘How sweet, how passing sweet is solitude!’). Mary had travelled from Paris to Sweden and Norway after witnessing the bloody streets of revolutionary Paris. The natural untamed beauty of Scandinavia would have seemed sweet indeed. In her letters (Letters Written during a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark) she wrote about these “rough” northern countries and the Nordic forest growing out of “iron-sinewed rocks”:

Sheltered from the north and eastern winds, nothing can exceed the salubrity, the soft freshness of the western gales. In the evening they also die away; the aspen leaves tremble into stillness, and reposing nature seems to be warmed by the moon, which here assumes a genial aspect: and if a light shower has chanced to fall with the sun, the juniper, the underwood of the forest, exhales a wild perfume, mixed with a thousand nameless sweets that, soothing the heart, leave images in the memory which the imagination will ever hold dear.

I remember being mesmerised by the shades of mauve, yellow, pink, white and grey streaking across the blue sky late into the evening and early morning. This is Mary Wollstonecraft’s sensory response to the northern night sky in summer:

Nothing in fact can equal the beauty of the northern summer’s evening and night: if night it may be called that only wants the glare of day, the full light, which frequently seems so impertinent.

Written in his male-centric, passionate and robust style, English-aristocrat-turned-revolutionary, Lord Byron (George Gordon Byron, 1788 – 1824) described the majesty of Rome’s Pantheon (“pride of Rome!”) in his lengthy narrative poem, ‘Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage’ (1812-1818):

Simple, erect, severe, austere, sublime—

Shrine of all saints and temple of all gods,

From Jove to Jesus—spared and blest by time;

Looking tranquility, while falls or nods

Arch, empire, each thing round thee, and man plods

His way through thorns to ashes—glorious dome!

Shalt thou not last? Time’s scythe and tyrants’ rods

Shiver upon thee— sanctuary and home

Of art and piety—Pantheon! —pride of Rome! (CXLVI)

For me, the Pantheon is Rome’s spiritual heart, infusing the immediate area with an energy that is both divine and human. The narrow streets and crooked cobblestone lanes that radiate out from this ancient temple (pan: to every god; theon: temple) provide a visual feast of art and architecture. I am eager to return.

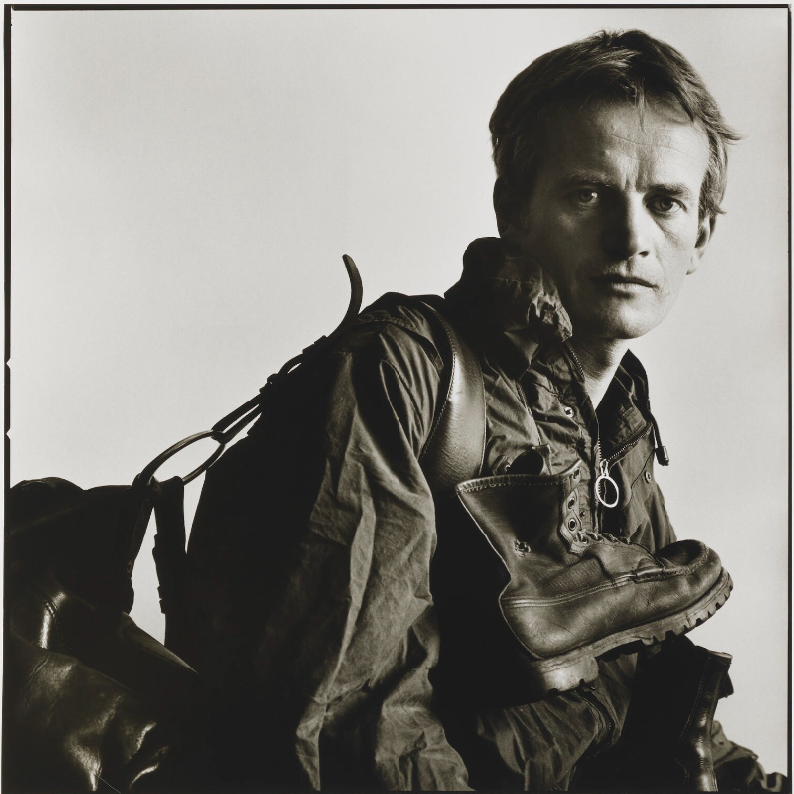

Bruce Chatwin (1940 – 1989,) was a British post-Vietnam-War traveller, content to travel alone and live in ‘native’ standards of comfort. He engages with the nature of human restlessness, which has been snuffled indefinitely by COVID-19.

Chatwin constantly shines an inquisitive light on ancient nomadic cultures, and espouses that freedom of the soul requires freedom from the vulgarity of modern culture. We find out in Chatwin’s ‘The Songlines’ (1987) that he quit his job in the ‘art world’ and went back to dry places: alone, travelling light.

This concept of travelling ‘light’ connects to Mary Kingsley (1862 – 1900), who travelled solo to West Africa in the 19th century with little baggage other than a long waterproof sack neatly closed at the top with a bar and handle. Her desire to seek out new territory as a lone, unencumbered traveller and escape a rigid Victorian society is the ultimate search for a balance between self and the world. Travelling ‘light’ brought Chatwin and Kingsley closer to the people among whom they travelled.

‘The Songlines’ is a reflection of Chatwin’s nomadic travels across Central Australia and the labyrinth of invisible pathways which meander all over Australia, known to Europeans as ‘Dreaming-tracks’ or ‘Songlines’; to the Aboriginals as the ‘Footprints of the Ancestors’ or the ‘Way of the Law’. Aboriginal Creation stories tell of ancestors wandering across the Australian continent in the Dreamtime creating songlines: singing out the names of the flora and fauna as they walked, and so singing the world into existence.

Bruce Chatwin didn’t believe in the ‘travel book’ full of facts. He was more interested in blending his ideas and travel experiences with fiction, history and myth. “To call it [Songlines] fiction isn’t strictly true, but to call it nonfiction is an absolute lie,” barked Chatwin.

On an even broader level, ‘The Songlines’ explores the nature of quests or pilgrimages that attempt to access sacred and ancient knowledge, linking travel, language and territory. Chatwin writes:

I have a vision of the Songlines stretching across the continents and ages; that wherever men have trodden they have left a trail of song (of which we may, now and then, catch an echo); and that these trails must reach back, in time and space . . .

If our ingrained ideas of how one should live one’s life can be left at home, then, as future, post-COVID-19 world travellers, we will be more like Chatwin, Piozzi, Montagu, Kingsley, Wollstonecraft and Harris, and less likely to import judgemental convictions as we encounter those who are different, or not so different. Like the nomad, we can travel ‘light’.

Writers can learn so much from these ‘early’ travel writers. If you’d like an assessment of your unpublished manuscript for reasons other than just an opinion regarding ‘place’, or an ‘edit with comments’ then I would love to ‘hear’ from you.

Manuscript Assessment? Editing?

If you are ready to have your writing edited, or you would like an assessment of your writing project, whether it is a complete manuscript or a work-in-progress, then please email me via my contact page with a brief overview. My editing is based on the Australian Style Manual (ASM) unless an author has been commissioned to write a book using the publishing house style guide.

Featured image:

Elephant carrying an obelisk, designed by the Gian Loenzo Bernini, unveiled in 1667 in the Piazza della Minerva, Rome, adjacent to the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva and behind the Pantheon.