Letters written by British suffragettes imprisoned in London’s Holloway Prison in the early twentieth century, and the Holloway brooch awarded to these women for their bravery on their release, send shivers down my spine. The Holloway brooch succinctly symbolises the militant struggle of the suffragettes as they fought tirelessly for the right of women to vote in political elections. Designed by Sylvia Pankhurst in 1909, its form is a metal grid with pointed ends adapted from the United Kingdom’s House of Commons portcullis gate symbol (a portcullis is a heavy gate typically found in medieval fortifications consisting of a latticed grille, which closes down vertically). The hanging chains symbolise prison restraints. The broad arrow, representing arrows on government-owned inmate garments, is enamelled with purple, green and white—colours associated with women’s suffrage (white: purity; green: hope; purple: courage).

The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU)—founded by Sylvia’s mother, Emmeline Pankhurst, in 1903—commissioned the Holloway brooch. First mentioned on 16 April 1909 in the WSPU paper, ‘Votes for Women’, the brooch was described as ‘the Victoria Cross of the Union’.

Currently, there is a small exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria (International) tucked away along a corridor on level 2 that caught my eye on a recent reconnaissance of the free exhibitions. The focus of the exhibition, as described by NGV curator Maria Quirk on Twitter (16 December 2019), is the ‘design material used in the women’s Suffrage movement’ (not sure why suffrage is capitalised in this context). I was looking for something to inspire me as 2020 looms—one of the Holloway brooches is on display.

Even though the exhibition focuses on women’s suffrage ‘design history’, I was drawn to the letters written by force-fed suffragettes in Holloway Prison, and the letters praising their bravery by suffragette leaders.

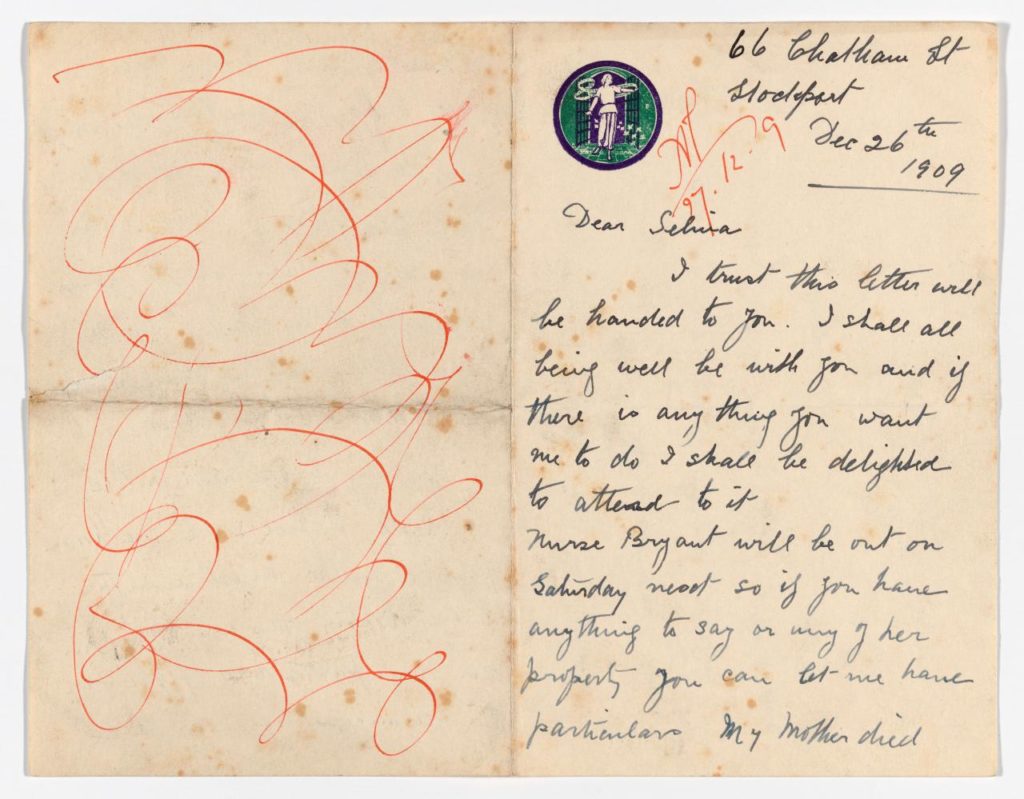

The image below is of a letter on display in the exhibition that was written in 1909 to Selina Martin (British suffragette arrested many times and force-fed in Holloway Prison. The NGV purchased her WSPU Hunger Strike Medal this year) by fellow British suffragette, Sarah Jane (Jennie) Baines, a feminist and WSPU activist. The letter ends: “keep your courage. No surrender. The mist will soon roll away and bring freedom and justice to our long neglected sex.” Following multiple incarcerations in prison due to her activism, Baines fled to Melbourne from London in 1913 with her family and worked tirelessly to support the Australian Women’s Political Association, which had links to the WSPU. The letter is handwritten on WSPU stationery featuring the WSPU logo designed by Sylvia Pankhurst. The logo, coloured with green, white and purple, depicts a woman stepping over broken chains as she walks through prison gates with doves, and a streamer with the words ’Votes for Women’, encircling her.

Jennie Baines (author), letter to Selina Martin, 26 December 1909, WSPU stationery. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

It’s disappointing that this exhibition is relegated to a walkway and overshadowed by the ticketed NGV blockbuster on the ground floor featuring (again) male artists. Why do the NGV’s winter and summer ‘blockbuster’ exhibitions continue to cough up a predominance of male artists, often two at a time, as a ‘compare-and-contrast’ (it seems to be a trendy trend) between contemporaneous male artists or the ‘old’ and the ‘new’? I acknowledge that many would view this as inspired curation and I’m sure (hope) the golden triangle of male NGV directors are pondering a future female artist-duo blockbuster as they dust off the last page of the decade and face the next decade of NGV exhibitions.

And so, back to those pioneering feminist suffragettes . . .

The global women’s suffrage movement grew out of a demand for women to be part of the electoral process and have the same rights to vote as men.

The word ‘suffrage’ has two meanings: a person’s right to vote in political elections; and, intercessory prayers for the souls of the dead taken from the Book of Common Prayer.

Women’s or woman suffrage is the right of women to vote in political elections.

Suffragette: a female supporter of the cause of women’s political enfranchisement, especially one working through organised (often militant) protest in Britain in the early 20th century. (Oxford English Dictionary)

Suffragist: an advocate of the extension of the political franchise, especially to women. (OED)

Australian non-Indigenous women were granted the Federal vote in 1902 and could stand as candidates in elections. In 1894, South Australian women gained the right to vote—the first women in the world to be able to stand as candidates in state elections. The state of Victoria finally passed a similar bill in November 1908, thanks to the work of suffragists Annie Lowe and Vida Goldstein, who co-founded the Victorian Women’s Suffrage Society 1884.

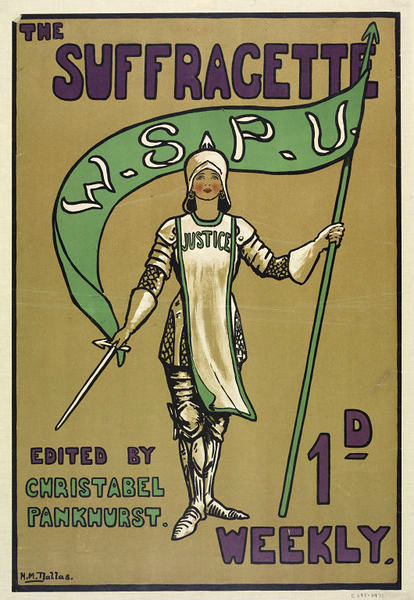

‘Votes for Women’ posters, banners and postcards were distributed in their thousands thanks to new technologies in printing. The rise of daily newspapers inspired the WSPU to produce its own weekly newspaper, ‘The Suffragette’, edited by Emmeline’s other activist daughter, Christabel Pankhurst. This woodblock printed poster (below) was designed by Hilda Dallas, an artist and member of London’s Suffrage Atelier, which produced pictorial publications for the WSPU. The poster features an image of Joan of Arc carrying the banner of the WSPU. As the British suffragettes became increasingly militant, Joan of Arc was adopted as their patron saint.

‘The Suffragette 1d Weekly’. Colour lithograph poster advertising the periodical edited by Christabel Pankhurst for the Women’s Social and Political Union. Hilda Dallas (designer). c.1914. 50.5 x 75.3 cm. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Emmeline Pankhurst was the heart and soul of the militant WSPU. Born in Manchester in 1858 into a radical political family, Emmeline married Dr Richard Pankhurst, a dedicated feminist barrister. Their daughters, Christabel and Sylvia, were also involved in the WSPU. By 1913, Emmeline had served three prison sentences, two for leading a deputation to Parliament on ‘Black Friday’ on 18 November 1910 and for inciting the public to ‘rush’ the House of Commons. In the wake of the window smashing of March 1912, she was sentenced to nine months in prison for conspiracy to commit damage.

On ‘Black Friday’, approximately 300 suffragettes marched to the House of Commons to protest at the failure of the first Conciliation Bill and the refusal of Prime Minister Asquith to meet with a WSPU deputation. The WSPU protesters endured violent aggression by the male police force, who physically abused the suffragettes, involving sexual assault.

William Monk, ‘Suffragette demonstration outside Houses of Parliament’, 1910, watercolour & pastel drawing; on the reverse in pencil reads: ‘Suffragettes sketched from actual scene’, © Museum of London

Suffragist campaigns, which included writing critical essays arguing for women’s legal and economic rights, and militant demonstrations, pushed forward women’s suffrage agenda. In 1918, the Representation of the People’s Act was passed in Britain entitling women over the age of 30, who met specific property requirements, the right to vote. On 2 July 1928, this act was extended to include women over the age of 21. Emmeline Pankhurst died on 14 June 1928.

On 15 May 2018, I visited the Museum of London to view the British women’s suffrage exhibition commemorating 100 years since the introduction of the Representation of the Peoples’ Act. The suffragettes’ militant actions and self-sacrifice as a united force was conveyed in a newly commissioned archival film that incorporated contemporary reflections of the relevance of the campaign. Objects on display in the exhibition included Emmeline Pankhurst’s Hunger Strike Medal and one of the Holloway brooches—potent symbols of the suffragettes’ determination to succeed, when words were not enough.

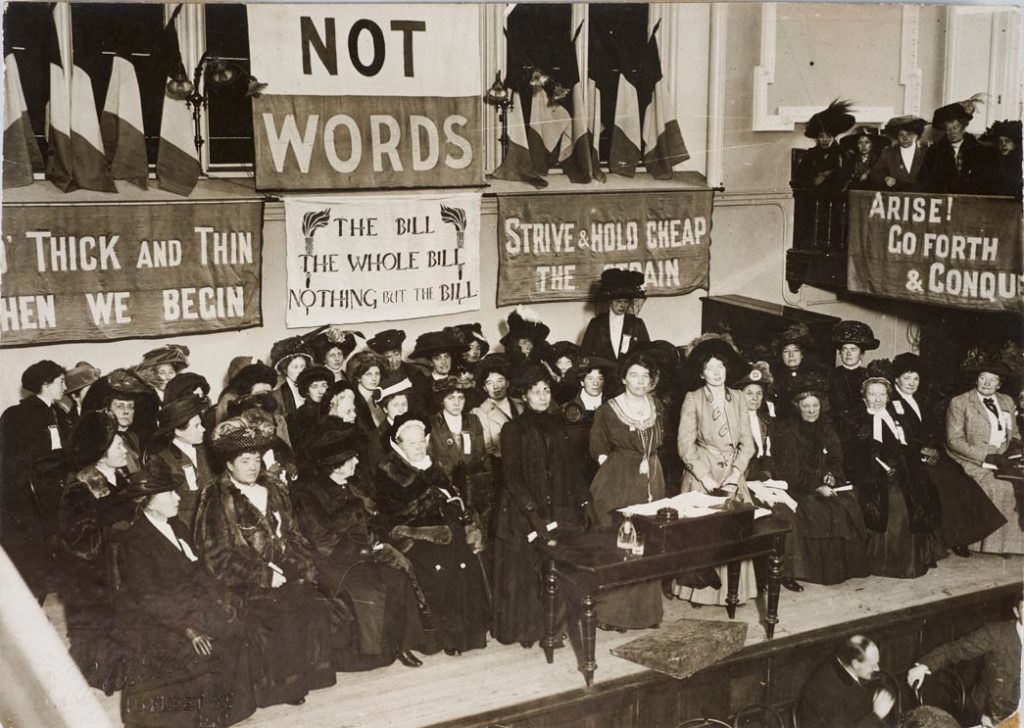

Emmeline, Sylvia and Christabel Pankhurst addressing supporters at a meeting held at Caxton Hall on ‘Black Friday’, November 1910. © Museum of London

References

Elizabeth Crawford, The Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928, London: Routledge, 2003

British Library/Black Friday pamphlet

National Gallery of Victoria, Krystyna Campbell-Pretty AM and Family Suffrage Research Collection

P.S. In 1921, Edith Cowan became the first woman member of an Australian parliament when she was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Western Australia. It wasn’t until 1962 that Indigenous Australian women were granted the right to vote.

Featured image: Holloway brooch, Sylvia Pankhurst (designer), Toye & Co., London (manufacturer), 1909, silver and enamel, 2.5 x 1.9 x 0.2 cm, National Gallery of Victoria