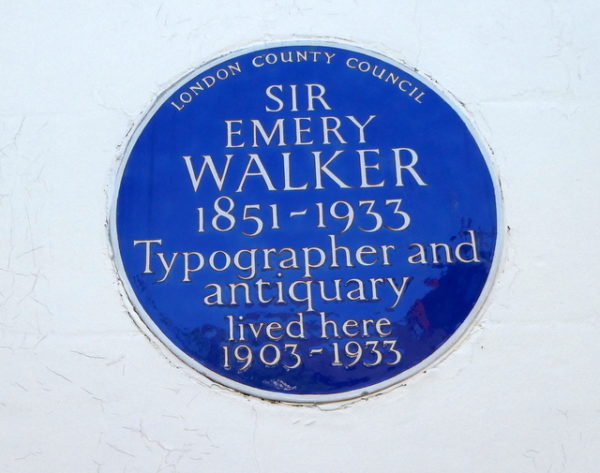

The handmade book and the manual craft of printing are brought into sharp focus in an Arts and Crafts house situated along a short stretch of the Thames River in Hammersmith, just a half-hour train journey from central London. I visited 7 Hammersmith Terrace on a sunny spring day on the 17th of May this year. Between 1903 and 1933, this was the home of Emery Walker (1851-1933), one of the key members of the Arts andCrafts movement. Walker was a distinguished typographer, printer and antiquary, and played a crucial part in the two most famous private printing presses in England at the turn of the twentieth century: William Morris’ Kelmscott Press, and Walker’s Doves Press. Owned and cared for by the Emery Walker Trust, the house has been touted as the best preserved Arts and Crafts home in Britain since it reopened in April this year following a three-month closure for conservation work. It was even shortlisted for a prestigious international award for ‘best museum opening of the year’ by the Apollo mag.

Public access to the house is by appointment due to small rooms being crammed with furniture, artefacts and decorative items (around 6,000 items were removed and catalogued during the renovations); only groups with a maximum of eight per group are admitted. Three upper floors are accessed by narrow stairs and there are steps down to the riverside garden. Understandably, the house is only open for three tours twice a week, and only during spring and summer (there is no electric lighting in the upper floors).Thankfully, I was in London for four days at the right time, but I booked online months before.

En route to the house, as is often the case in London, there was an obstruction on the Tube line causing major delays, so we had to reroute, adding time to our journey. Out-of-breath, but with hopeful anticipation, I knocked on the green Georgian door, at number 7 Hammersmith Terrace, a few minutes late for our 11 am tour. The door opened, and all was calm. I couldn’t help noticing that the original linoleum on the hallway floor looked like a Morris & Co. design (I found out later that it is).

We joined the group in the dining room. Sun was streaming through the window, and for a frozen moment of delight, I was drawn to the new spring growth in the garden and the Thames River beyond. Birdsong turned my attention to the William Morris-designed, wool-woven ‘bird’ hanging, which, we are told, had originally adorned the entire length of William Morris’ drawing room at Kelmscott House (now the headquarters of the William Morris Society just a few minutes away at 26 Upper Mall), Morris’ London home for the last eighteen years of his life; the hanging has been cleaned and now adorns the wall, complementing the Morris ‘Willow’ wallpaper. Apparently, Walker’s house has one of the largest in-situ collections of Morris & Co wallpapers in the world.

We climbed the stairs and I caught my breath as the curator whipped off a sheet from the Barnsley bed (which had been on loan to the V&A until after the conservation) to reveal an exquisitely embroidered coverlet by May Morris (William Morris’ daughter), who lived at number 8 until 1923 and made it for Emery’s wife, Mary Grace. This was Dorothy Walker’s bedroom, which still has an original William Morris carpet and his 17th-century chair with a cushion embroidered with ‘MM to EW’ (May Morris to Emery Walker) donated to Walker by May Morris after her father’s death. The Morris ‘Tulip’ wallpaper has been cleaned, but curatorial inspiration has left a small square of original wallpaper uncleaned, showing the surface grime of a century. Our group is told that Dorothy (1878-1963), Walker’s daughter, and her nurse-companion Elizabeth de Haas (1918-1999), deliberately kept the house as it was when Emery Walker died (only the bathroom and kitchen were modernised in the 1960s), and that it therefore “constitutes an almost intact survival of an Arts and Crafts interior with no museological intervention”.

The house’s contents and furniture (architect-designer Philip Webb, who held Walker in high esteem, bequeathed all his possessions to him on his death in 1915, including his Arts and Crafts-designed bookcases, display cabinets and chests) were created, or collected, by Walker and his friends, including T E Lawrence, Rudyard Kipling and George Bernard Shaw.

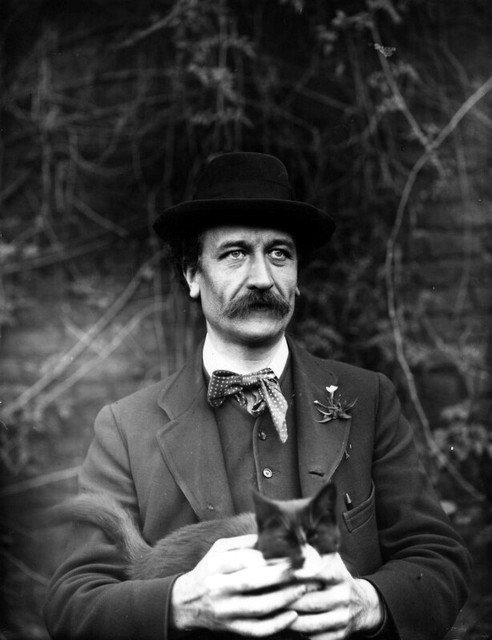

Sir Emery Walker by Unknown photographer, modern bromide print, circa 1890, © National Portrait Gallery, London

I came across Emery Walker (who was knighted in 1930) a few years ago via William Morris (1834-1896; English designer, poet and craftsman). Walker was Morris’ master printer, having first met each other in 1883 at the Metropolitan Railway Station on their way back to Hammersmith after a socialist meeting at Bethnal Green (Walker moved into number 7 with his wife and children in 1903, but they spent the previous 24 years living at 3 Hammersmith Terrace). From that time on they formed a close friendship and became active members of the Hammersmith Socialist League. Morris developed an interest in printing through the publication of his own writings, and Emery Walker. However, although Walker is best known for his fine printing and typography, he earned his living printing pictures and making photographs. In 1885 he founded the firm of Walker and Boutall, Automatic and Photographic Engravers with his friend Walter Boutall. The company developed a technique of engraving for illustrating books with photographs and artworks, which was considered the best in the business.

A lecture on the history of typography given by Walker in 1888 at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, London, inspired Morris’ printing activities and led to the establishment of the Kelmscott Press (1891), considered the beginning of the private press, or fine press, movement in England, in direct response to the impact of the Industrial Revolution. Mechanised printing had enabled the mass production and distribution of books to broader audiences, but at the same time often resulted in poor quality books. Morris was determined that his books would be finely crafted and made of the best materials. Walker, with his trade connections, was able to provide practical help throughout the seven years of the Kelmscott Press’ existence. Walker photographed and enlarged typefaces for Morris to study, and he also assisted with photographing the illustrations. Together they studied early printed books dating back to medieval times.

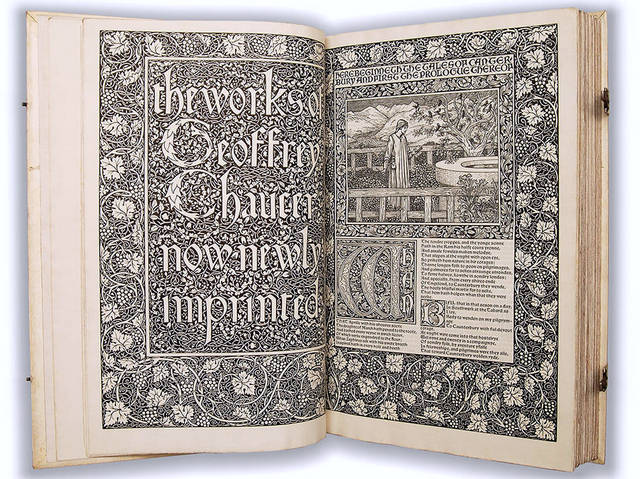

A page from ‘The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer’, 1896, Kelmscott Press, http://www.victorianweb.org/art/design/books/63.html, photographer: Peter Harrington

The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer published in 1896 by the Kelmscott Press was a triumph, the culmination of William Morris’ vision for an ideal book. It embodied his love of medieval literature and art, as well as his passion for beauty. Its 87 wood-cut illustrations are by Edward Burne-Jones, the celebrated Victorian artist, who was also Morris’ close friend (there is an exquisite portrait of May Morris by Burne-Jones hanging on the wall of the Walker house). The illustrations were engraved by William Harcourt Hooper and printed in black, with shoulder and side titles. Some lines were printed in red, using Chaucer type, with some titles in Troy type. The whole was printed on Batchelor handmade paper watermarked: Perch. (source: www.bl.uk/collection-items/the-kelmscott-chaucer)

“Indeed when the book is done, if we live to finish it, it will be like a pocket cathedral – so full of design and I think Morris the greatest master of ornament in the world.”

– Edward Burne-Jones, Letter to Charles Eliot Norton, 1894

The pair spent four years working on this “pocket cathedral”. Trial pages were printed in 1892, while final production began on 8 August, 1894. The first two copies of the book were delivered to Morris and Burne-Jones on 2 June, 1896. Morris died four months later on 3 October, 1896. 425 copies were eventually printed and sold for £20 each. This wonderful book will be a focus of my next art history course; we will visit Melbourne’s State Library of Victoria for a private viewing of the Library’s edition. William Morris and Emery Walker produced fifty-two works in sixty-six volumes until the Kelmscott Press closed following Morris’ death.

This was, however, only the beginning of a long career in private presses for Walker, who in 1900 founded the Doves Press (now The Dove Inn!) with Thomas Cobden-Sanderson (he was married to Annie Cobden, a socialist and suffragette, with the couple both taking the surname Cobden-Sanderson), until they went their separate ways in 1909 (a spiteful Cobden-Sanderson threw the Doves Press founts into the Thames from Hammersmith Bridge; some have been retrieved). Walker was also later associated with C.J. St John Hornby’s Ashendene Press. We were shown some of Walker’s original types of matrices, the basis of his printing processes, at the end of the tour. His complete collection of private press books are now in the Emery Walker Library at the Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museum.

Number 7 Hammersmith Terrace documents a life lived quietly by the Thames; Emery Walker “was always something of a back-room boy, happiest in the role of technical adviser.”* Leaving the house, we walked along the riverside promenade in the sun towards Hammersmith Bridge, dropping into Kelmscott House on the Upper Mall for a short visit. We imagined Walker taking the same route to his friend’s house almost on a daily basis.

My passion for ‘living’ house-museums that maintain the sensibility and treasures of the departed owner was well-and-truly satisfied in Emery Walker’s House, which embodies the Victorian Arts and Crafts aesthetic to perfection. However, I wonder if Walker and Morris would have approved of the fences that now separate the group of seventeen brick-row houses at Hammersmith Terrace, originally open at either side as a communal space for the private use of the owners and tenants. This open, back-yard arrangement would have been so conducive to Walker and Morris’ socialist philosophies and their creative enthusiasm for sharing ideas about the beauty of manual crafts.

*Alan Crawford, ‘Emery Walker: Printer of Pictures’, 2007, hand-printed, limited edition no. 19