This is my second article about words that have been used in the wrong context by writers whose manuscripts I have assessed, edited or proofread. Was it a historic or historical event? Was it a continual or continuous noise? Is someone illusive or elusive? The confusion can occur because these words are spelt similarly or sound similar, or both, so it’s understandable that they are often misused.

historic or historical?

You might think that these two words mean the same thing, but they convey two separate ideas about how something relates to history. The word historic means ‘famous or important in human history’, whereas historical means ‘concerning history’. Hence, something that has happened in the past is historical, but something momentous, which is a landmark in history, is historic. A building can be historic (Westminster Abbey); so can a speech (Martin Luther King: “I have a dream …”) or a battle (the Battle of Waterloo) or a natural disaster (the eruption of Mount Vesuvius and destruction of Pompeii in CE 79).

The middens hold clues to historic environmental conditions.

They must salvage historic buildings damaged in the earthquake.

Many stones with historic markings were placed in the museum.

If you’re writing about something from the past, the reference is historical.

The set designers of the play, ‘Great Expectations’, recreated rooms with historical accuracy, making them look just like they would have in the early nineteenth century.

What are the historical details of your ancestors’ immigration to Australia?

Our knowledge of the events that were yet to transpire when this image was painted makes it a personal and historical document.

By the way, to clarify: writers often use the indefinite article an in front of these two words, but if you pronounce the h- in either historic or historical (which is what we do today), you should use a rather than an before them.

continual or continuous?

For many, it doesn’t really matter, and the distinction is not strictly observed because the words have not always been differentiated. But to be correct, continual refers to things that happen repeatedly, or frequently, but not constantly; for example, his continual lateness. The continual action doesn’t happen ceaselessly, but it does happen regularly, with intervals between.

The continual street repair disrupted traffic for nearly two years.

“I’m fed up with these continual interruptions,” said Dr Brydon as he resumed his lecture.

Continual restlessness pervades his life.

The word continuous should only be used to describe something that goes on and on without stopping: an uninterrupted sequence; for example, the drone of a plane engine, the flow of a river, the motion of the planets around the sun, and the heartbeat are continuous because they never stop.

There was a sound of light regular breathing and a continuous murmur, as of very faint voices remotely whispering. (Brave New World)

That furious brown water, swirling, foaming, leaping and thundering, represented for Romantics the continuous force of thought.

Indigenous Australians represent one of the oldest continuous populations in the world.

elusive or illusive?

‘Elusive’ is the most commonly used of these two words, and in most cases used correctly when the writer means that something or someone is hard to find, pin down, or define.

Happiness is an elusive concept, rather like love.

Her ideal life always seemed elusive to her.

He proved an elusive foe for law enforcement.

However, if something misleads or deceives you, it is illusive. If you think you see a leprechaun in your back yard, but it seems to vanish into thin air then you can describe the vision as illusive because it was never there at all. It was just an illusion! So if something or someone is described as illusive, then it/he/she is not real—non-existent. The word comes from illusion, originally meaning “to mock, to jest”.

There were no shadows under the trees but everywhere a pearly stillness, so that what was real seemed illusive and without definition. (Lord of the Flies)

The plane crashed into the building as if controlled by some illusive invisible evil.

The illusive quality of privacy is a recurring theme of literature.

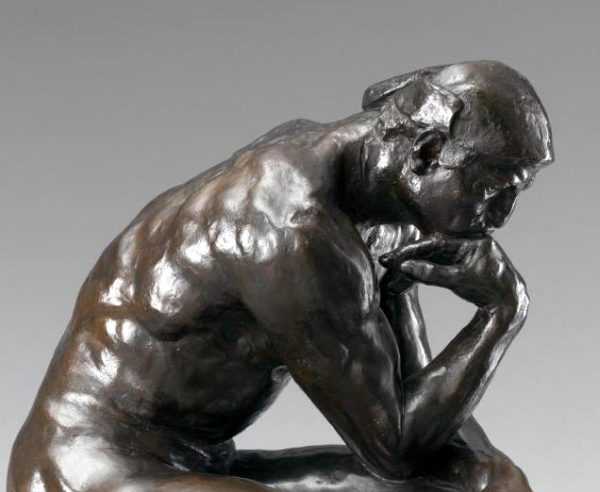

Featured image: Auguste Rodin, The thinker, (Le Penseur), detail, 1881-1882 (cast 1884), National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne