If the name Vanessa Bell (1879-1961) doesn’t ring a bell, then maybe her younger sister’s name, Virginia Woolf, does. Happily, my recent stay in London coincided with an exhibition of Vanessa’s art at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, and I also visited Charleston House, her charming rural bolthole in East Sussex. Combining these visits enabled me to better understand this artist who has been habitually overshadowed by her younger sister’s literary accomplishments and their notoriously unconventional life. Vanessa Bell played a pivotal role in twentieth-century British modernist art with her inventive visual language expressed through a fluidity of painterly technique, form and colour combinations.

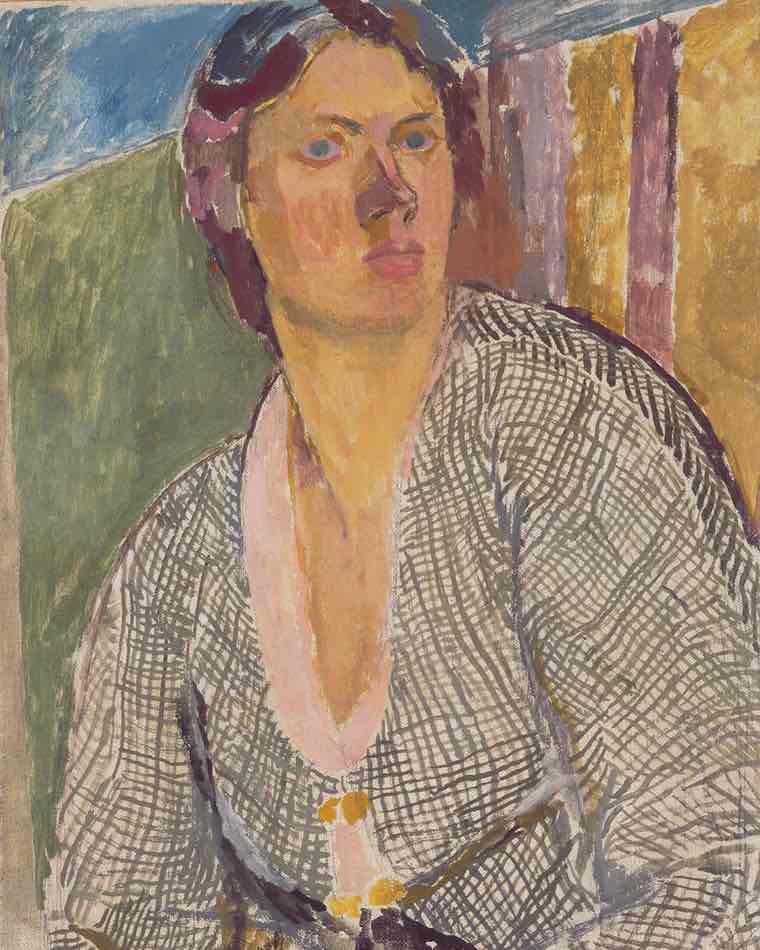

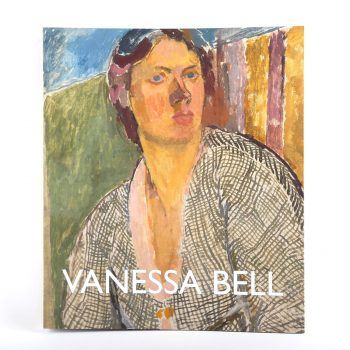

Vanessa Bell, ‘Self-Portrait’, c. 1915, oil on canvas laid on panel, 63.8 x 45.9 cm, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund, © The Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy of Henrietta Garnet

Born into a privileged family in Victorian London, Vanessa Stephen had a distinctive way of seeing the world around her, which was given free rein as a child. At the age of 22 she studied at the Royal Academy Schools, but her involvement with avant-garde artists and writers that formed the Bloomsbury Group a few years later consolidated her artistic trajectory. In 1907, she married fellow Bloomsbury member and art critic Clive Bell, with whom she had two boys, Quentin and Julian.

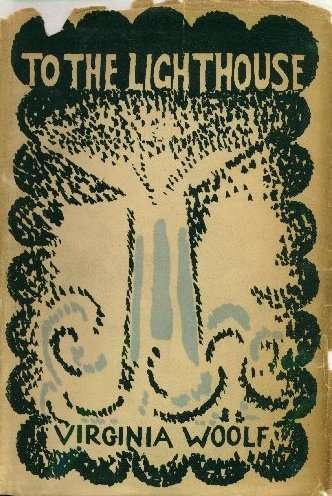

On Tuesday 30 May I travelled to Dulwich Picture Gallery, a few miles south of London, to view the first major monographic exhibition of Vanessa Bell’s work. This year DPG celebrates its 200th anniversary as the first purpose-built public gallery in Britain; it was designed by the acclaimed architect, Sir John Soane (1753-1837). The exhibition, Vanessa Bell: 1879-1961, has been applauded for embracing the many complexities of Vanessa Bell’s long artistic career, from her student works in 1905 to her last self-portraits before her death in 1961. Curated by Toronto writer and curator Sarah Milroy, and the (then) director of DPG, Ian Dejardin, Bell’s works were on loan from private lenders; London’s Tate and National Portrait Gallery; The Charleston Trust; the MET, New York; and the Yale Center for British Art, Connecticut. Arranged thematically, the exhibition revealed Bell’s inventive work in the genres of portraiture, still life, interiors and landscape. Approximately 100 oil paintings as well as fabrics, works on paper, photographs and related archival material showcased her bold experimentation with abstraction, colour and form inspired by the contemporary art of Picasso, Matisse and the Post-Impressionists such as Paul Cézanne. There was also an assortment of Vanessa’s dust jackets on display, which she designed for Virginia Woolf’s books.

Vanessa Bell, ‘To the Lighthouse’, 1927, dust jacket for Virginia Woolf’s book, 19.2 x 13.5 x 3.9 cm, University Library, Toronto

The first room in the exhibition displayed early-career portraits of Vanessa Bell’s many friends, mainly her Bloomsbury chums such as the writer Lytton Strachey, the poet Iris Tree, and Roger Fry, the acclaimed art critic, art historian and painter with whom she a three-year affair. Portraits of her much-loved sister, Virginia Woolf, and Bell’s remarkable 1915 self-portrait (above) are stand-outs. The portrait of fellow artist Duncan Grant reflected in a mirror (c. 1916) is telling: he said he realised she was in love with him when he noticed her staring at him as he shaved. Grant was charismatic and handsome, and it was a bold move to fall in love with this predominantly gay man, but their love endured for the rest of her life. With her ingenious choice of colour, sometimes bright, sometimes dull, and her varied brushwork, Vanessa played with traditional notions of portraiture, creating her own expressive interpretations of the sitter.

Vanessa travelled to Paris and other parts of Europe many times, but the Manet and the Post-Impressionists exhibition held at London’s Grafton Galleries in 1910, organised by Roger Fry (who coined the name Post-Impressionist), inspired her to pursue line and colour almost to the point of abstraction. In particular, Cézanne and Degas had a profound influence on Bell, as did Picasso and Matisse. In 1912, alongside Picasso and Matisse, Vanessa exhibited her work in the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition at the Grafton Galleries. “All was a sizzle of excitement, new relationships, new ideas, different and intense emotions seemed crowding into one’s life,” wrote Vanessa. She was liberated by Post-Impressionism and dared to have a fling with pure abstraction; ‘Abstract Painting’ (c.1914, image below) is one of only four non-representational paintings within Bell’s oeuvre. She sought more freedom of expression through figuration.

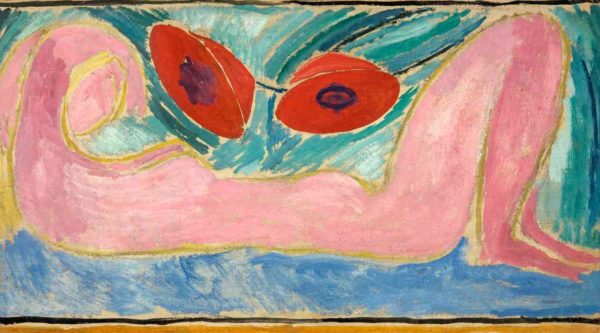

Two years later Vanessa painted ‘Nude with Poppies’ (featured painting, © The Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy of Henrietta Garnet). Believe it or not, this is a portrait of her husband Clive’s lover, Mary Hutchinson, a cousin of Lytton Strachey and high-society woman. Painted for Hutchinson’s bed-head, a pink reclining nude is overwhelmed by two giant red poppies. What was Vanessa thinking when she painted this nude of her husband’s lover? You may well ask: Vindictive? Tongue-in-cheek? Congratulatory? After all, affairs were ho-hum amongst the Bloomsbury chums. Vanessa had her own affairs: Roger Fry is believed to be the first, but the longest-lasting and all-consuming affair was with Duncan Grant. Her daughter Angelica believed Clive was her father until, at 17, she found out that Duncan was her biological father. Angelica ended up marrying David “Bunny” Garnett, the writer and publisher who had been Duncan’s long-time lover and was present when Angelica was born.

Vanessa Bell, ‘Oranges and Lemons’, 1914, oil on cardboard, 76 x 54 cm, private collection, © The Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy of Henrietta Garnet

In the middle room of the exhibition was a carefully selected group of still-life paintings: some sedate and dark, others light and ethereal, but my favourite was ‘Oranges and Lemons’ (left), an explosion of colour, shape and line—a celebration of Duncan Grant’s gift of oranges and lemons sent from Tunis in January 1914. Vanessa wrote to Duncan, “They were so lovely that against all modern theories I stuck some into my yellow Italian pot and at once began to paint them. I mean one isn’t supposed nowadays to paint what one thinks beautiful. But the colour was so exciting that I couldn’t resist it.”

Invariably, Vanessa Bell’s art is grounded in her life shared with others, and the environment in which she lived. This exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery introduced me to her art and life; a few days later, her East Sussex farmhouse gave me a greater sense of the essence of this artist as a woman: mother, wife, sister, lover, friend, gardener, decorator. In October 1916 Vanessa Bell moved to Charleston near Firle in Sussex with her sons; Duncan Grant and his current lover David Garnett; Duncan’s dog Henry; and various domestic help. In a letter to Roger Fry in 1916, she wrote:

It’s most lovely, very solid & simple, with flat walls in that lovely mixture of brick & flint that they use about here, & perfectly flat windows in the walls & wonderful tiled roofs. The pond is most beautiful with a willow at one side & a stone – or flint – wall edging it all round the garden part, & a little lawn sloping down to it, with formal bushes on it. Then there’s a small orchard & the walled garden . . . & another lawn or bit of field railed in beyond. There’s a wall of trees – one single line of elms all round two sides which shelters us from west winds.

After living at Charleston for three years, Vanessa painted ‘View of the Pond at Charleston’ (image below) as she stood before an upstairs window looking at clouds reflected on the surface of the pond. Her grandson Julian Bell writes with great insight about the painting in the DPG exhibition catalogue: “. . . the clouds seem to cancel its [the pond’s] depth, yet in the midst of the water’s expanse there is an abrupt plunge, where we are drawn into the interior of a jug that stands on the window ledge. The cast shadow on the jug’s inner lip is the hinge where the scene’s summery warmth points beyond itself, towards an unseen – though no less inviting – darkness.” The view is intensified due to the sight-angle being skewed and recession into the distance being denied. Although the forms and patches of colours mimic Cézanne, the Post-Impressionist hero for modernist painters, and the decorative marks suggest Matisse, Bell has created her own innovative composition that is harmonious in both colour and form.

Vanessa Bell, View of the Pond at Charleston, c 1919, oil on canvas, 61.5 x 65.9 cm, Museums Sheffield

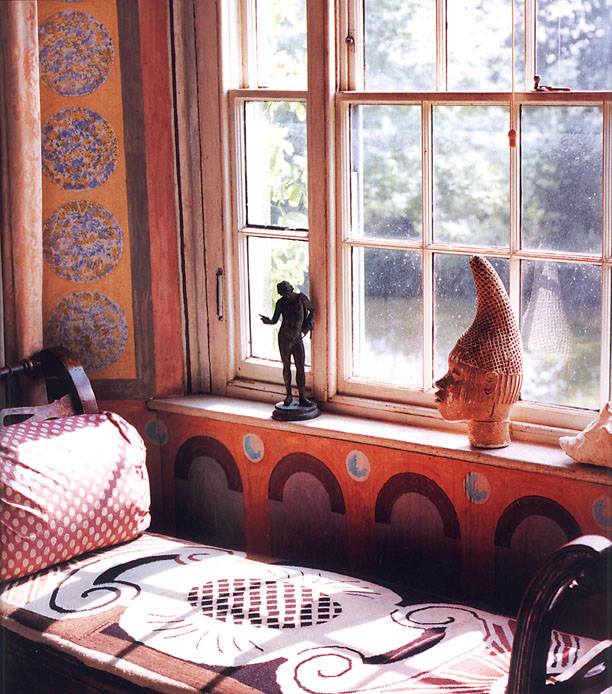

The painted furnishings and objects inhabiting Charleston House not only reflect Vanessa Bells’ Post-impressionist and Cubist aesthetic but the unfettered artistic life within its boundaries; everything begs to be handled. Her designs helped define the output of the Omega Workshops, the artists’ co-operative for decorative arts founded by Duncan Grant and Roger Fry, and which operated between 1913 and 1919. Vanessa, Duncan and Roger created simple abstract designs for textiles, furniture and ceramics. The DPG exhibition displayed fabric samples of her bold designs, but here at Charleston it was as if Vanessa and Duncan had just finished another creative collaboration and left the room: abstract and figurative patterns stencilled on walls; motifs painted on furniture, doors, curtains, fireplace surrounds, fabrics and pottery. I was reminded of William Morris’ Red House—both houses are a testament to the informal co-operative venture by a group of artist friends who saw art as a way of life in every way.

Vanessa Bell’s designs reflect the simplicity of life that she craved from her bohemian bolthole, enabling her to break free of repressive values. Her farmhouse in East Sussex represented freedom. This is Roger Fry’s perceptive appraisal of Charleston’s residents: “It really is an almost ideal family, based as it is on adultery and mutual forbearance and with Clive the deceived husband and me the abandoned lover. It really is rather a triumph of reasonableness over the conventions.”

Charleston was Vanessa’s permanent home during the Second World War as her pacifist family fled the bombing of London. She continued to live there most of the time until her death in 1961. Her life was tragically punctuated by the death of her son Julian at the age of 29, who for a short time was an ambulance driver in the Spanish Civil War (1937); and by Virginia’s suicide by drowning in the river Ouse (1941). Her late self-portraits attest to Vanessa’s gradual withdrawal and self-reflection, but she never stopped painting—patterns, shadows and the effects of light on colour.

Vanessa Bell, ‘Self-Portrait’, 1958, oil on canvas, 45 x 37 cm, The Charleston Trust, © The Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy of Henrietta Garnet

A final word from Sarah Milroy:

Unconventional in her approach to both art and life, Bell’s art embodies many of the progressive ideas that we still are grappling with today, expressing new ideas about gender roles, sexuality, personal freedom, pacifism, social and class mores and the open embrace of non-British cultures.

I was delighted to be gifted this impressive exhibition catalogue with essays by Vanessa Bell scholars.

Post Script:

After experiencing Charleston, I couldn’t return to London without visiting Virginia Woolf’s bolthole, a long walk or short bicycle ride from Charleston across the South Downs. Monk’s House is much more modest and rustic than Charleston, but equally atmospheric with, of course, furniture painted by Vanessa and Duncan.

Fascinating. I never knew she painted!

Thank you for bringing her work to light.

nita

I was lucky to find out so much more about Vanessa. In the past her light has been dimmed by others in the Bloomsbury Group, and Virginia.

Thank you Nita.