Spanning one long white wall, painted cross-form stars crowd vertical rectangles of bark after bark, giving the effect of twinkling stars moving across the night sky; on the opposite wall, shimmering cross-hatched lines painted on barks using earth ochres, mimic the ancient rippling of land in one of the driest areas of Australia, hardened by the sun, but saved by the eternal presence of water. These bark paintings on display at the TarraWarra Museum of Art (TWMA) exhibition ‘Earth and Sky’ were created by two artists from Arnhem Land in northern Australia. The surface vibrancy of their paintings not only reflects the energy of ancestral forces that pervade the artists’ ‘country’, but also the artists’ Dreamings and philosophies about spirituality that extends to all humanity.

At the opening of this exhibition, on a brilliant autumn day at the end of March, Hetti Perkins, renowned curator of Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander arts, author of the book ‘art+soul’ (and presenter of the associated television series), sits cross-legged on a chair next to Victoria Lynn, TWMA’s director. Lynn asks questions of Perkins, who has curated this show, and they chat about the art on display. It is apparent that the two women are not only colleagues, but friends, easy in conversation with each other. Consequently, the subject moves seamlessly from art to politics—in fact, Hetti insists that the two are intertwined. We are reminded that it’s fifty years since her father, Charles Perkins, led the legendary Freedom Ride to expose racism in Australia; now, his feisty daughter encourages Indigenous artists to be cultural ambassadors for their people. Kuninjku artist, John Mawurndjul, born in 1952 in the freshwater country of western Arnhem Land, sits in the front row facing Hetti, listening intently to what she is saying, and nodding when she asks him to clarify aspects that relate to his family and art.

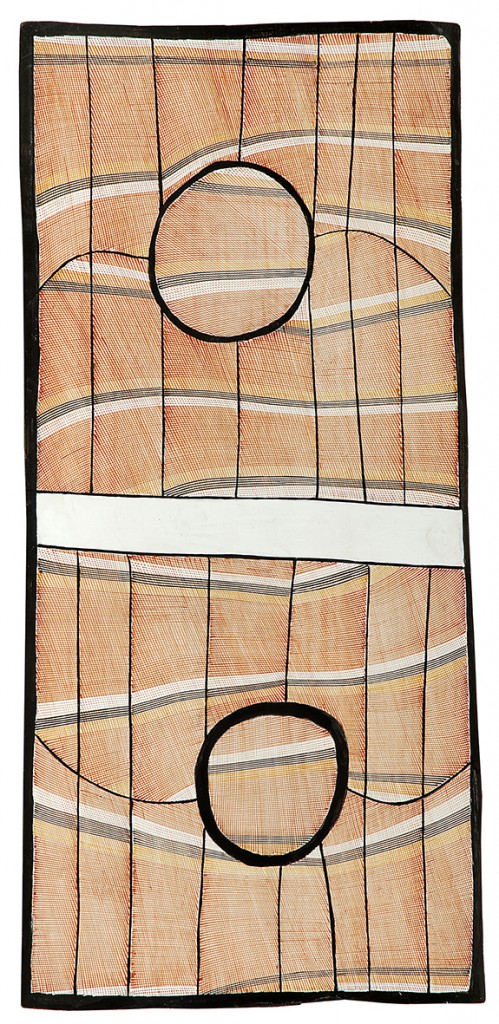

John Mawurndjul, ‘Billabong at Milmilngkan, 2007, natural ochres on eucalyptus tetradonta, 126 x 58 cm, Casper Wald Collection, Melbourne, © John Mawurndjul.

As I listen to Victoria Lynn and Hetti Perkins, I peruse Mawurndjul’s bark paintings hanging on the wall behind them. His art reveals his strong sense of ‘country’ as a sacred place that does not look to the horizon and beyond, but to the earth and waters coursing through the land traversed by his ancestors. The optical effect of his cross-hatching (‘rarrk’) suggests the presence of different djang (beings that created the artist’s land and whose spirits remain today) and Ngalyod, the rainbow serpent, who exist beneath the surface and continue to act as a conduit between the past and the present.

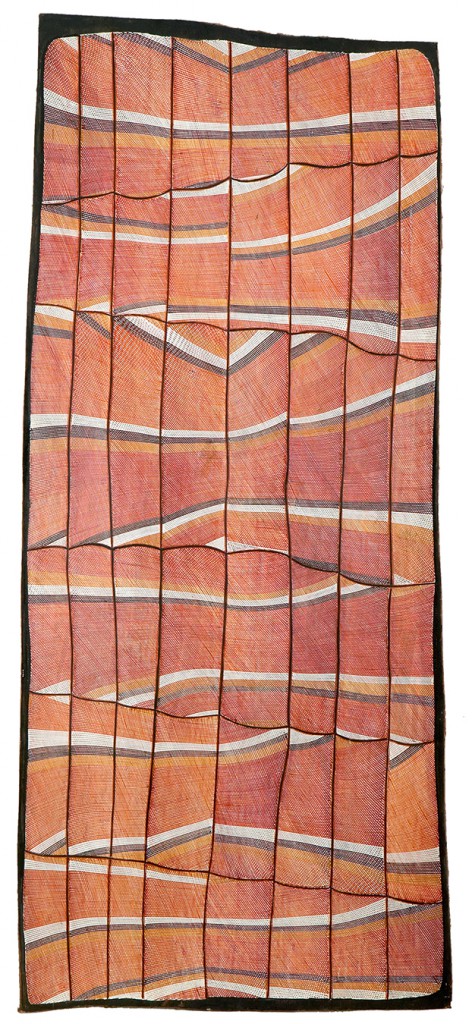

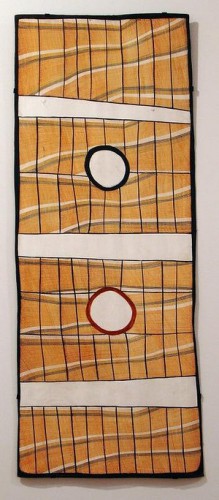

In my opinion, context adds to the visual interest of any art work; if the viewer has an idea or a perception of the artist’s intention, which may or may not connect with his or her life story, viewing becomes a more rounded and satisfying experience. When art represents the significance of a place for the artist then it has an even greater resonance with the spectator. Billabong at Milmilngkan (2007) and Milmilngkan (2006) represent significant sites in Mawurndjul’s homeland at Milmilngkan: the circular motifs indicate waterholes, and the grids and lines can be interpreted as water courses or even underground tunnels created by Ngalyod, linking the different waters. The cross-hatched infill in warm red and yellow ochres spreads across the bark, not only conveying a dynamic impression of the shimmering expanse of Mawurndjul’s country, but also of his sacred Dreamings, or ancestral stories. The white and grey cross-hatched lines are described by Perkins “as the essence of ancestral spirits”. These ‘abstract’ bark paintings also represent body painting for the sacred Mardayin ceremonies.

John Mawurndjul, ‘Milmilngkan’, 2006, natural earth pigments on bark, 160 x 70 cm, Courtesy of the artist and Annadale Galleries, Sydney, © John Mawurndjul.

There is no doubt that Mawurndjul’s bark compositions reflect and celebrate the spiritual essence and power of his land; yet within the animation, which pervades every inch of the surface, there is an undercurrent of absolute stillness. As I stood fairly close to the paintings and concentrated on the network of fine lines vibrating with energy, some sort of silent force took hold of me, suspending me in front of it, out of time. In fact, for me, Mawurndjul’s works inhabit a domain beyond animation and beyond stillness: the strength of the grid seems utterly indestructible, a density that is impenetrable, and a timelessness assured.

Gulumbu Yunupingu, ‘Ganyu’, 2009, natural pigments on bark, 113 x 67 cm, purchased with funds provided by the Aboriginal Collection Benefactors’ Group 2010, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Photo: AGNSW © Estate of the artist, Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala.

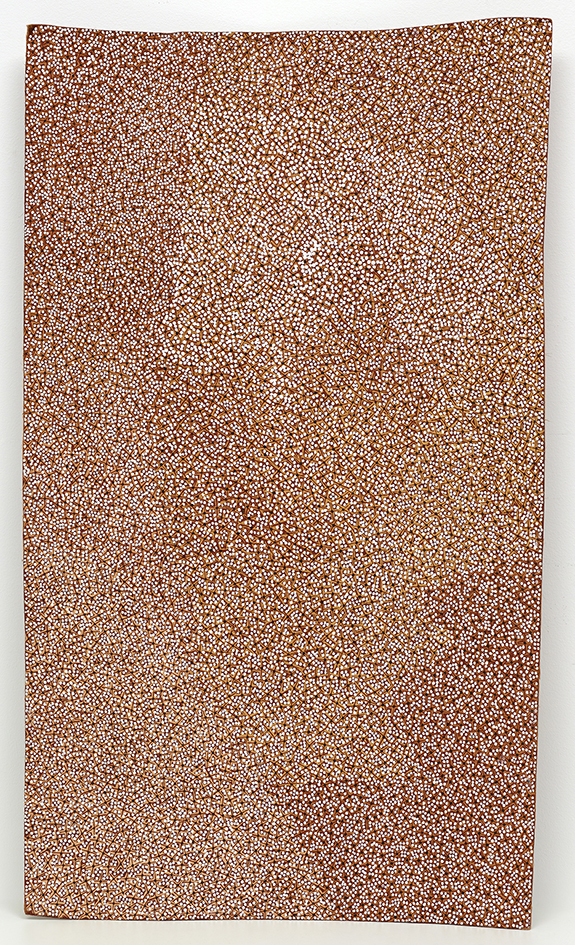

Expressing a similar timelessness are the bark paintings of the late Gulumbu Yunupingu (1945–2012) hanging on the opposite wall. They were inspired by sacred songs which her father used to sing about the stars: traditional Gumatj stories of the Pleiades and other constellations. She has painted Garak (the universe) and the Ganyu (stars) and galaxies, using a template of dynamic marks and dots that is unique, yet varied, within every bark painting. Hetti Perkins explains how “the countless stars in deep space that cannot be seen by the human eye [are] represented in Yunupingu’s paintings by the floating scrim of dots that underlie the crossform stars.” Perkins also relates how Mrs Yunupingu painted these incredibly beautiful stars: “she would begin each star motif with a cruciform ‘body’ upon which the spirit was delicately traced in an alternate colour and completed by the placement of the ‘eye’ at its centre.” These bark paintings are the artist’s expression of the mysterious celestial realm, which reaches out beyond the twinkling stars in the night sky of her beloved ancestral country, devoid of urban lights.

Gulumbu YunupinguGarak, The Universe 2008, natural earth pigments on eucalyptus bark, 137 x 77 cm, Purchased 2009, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, © Estate of the artist, Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala

Yunupingu’s paintings not only reveal a depth of Yolngu knowledge of her ‘country’ and its magical night sky, but they express her desire to represent the vast cosmos, and in doing so, embrace humanity, connecting us all across the globe whenever and wherever our gaze lifts to the sky. This expansive view can perhaps, in part, be explained by her distinguished family history, which consists of a diverse range of people and interests. Hetti Perkins writes in the catalogue:

The names of her sisters and brothers, Galarrwuy [former Northern Land Council Chair and Australian of the Year], Mandawuy [lead singer of Yothu Yindi and former Australian of the Year], Nyapanyapa and Barrupu are well known in Australian politics and the arts. Yunupingu’s father was a signatory to the historic Yirrkala Bark Petitions protesting mining on Yolngu land, now on permanent display in Parliament House, Canberra, and, along with her husband Mutitjpuy Munungurr, was among the artists who contributed to the Yirrkala Church Panels (1963). Yunupingu’s first solo exhibition, at Melbourne’s Alcaston Gallery in 2004, was held in the same year she was awarded first prize in the 21st Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award for her installation of three larrakitj (hollow log memorial poles). Many people also knew of Yunupingu as a healer, well versed in the traditional knowledge of her people, which she shared with other women at Dilthan Ngapakinha: The Healing Place, in north east Arnhem Land.

Although the legitimacy of aboriginal bark paintings as belonging within the domain of contemporary art practice has been debated, Perkins is convinced that these bark paintings by Mawurndjul and the late Gulumbu Yunupingu “not only reveal their singular vision, they herald the emergence of bark painting as a vital form of contemporary art practice that eloquently asserts their people’s enduring connection to country – the earth and sky and all in between.”

I always enjoy the TWMA Vista Walk Gallery, not only because it provides amazing views down the valley, but also because it allows daylight to penetrate the space through the narrow, vertical windows facing west and the large window facing north. But it was empty when I was at the opening of this exhibition. If these barks, painted with natural earth pigments, were hung in this light-filled space, I imagine them ‘singing’ with the landscape. One thing pure daylight does, even when it’s fading, is to bring out an inner glow in paintings. In my opinion, this would have added an even greater depth and vibrancy to these bark paintings. However, due to the number of barks on display, and perhaps a clever curatorial decision to face-off sky with earth, they have been hung in the cavernous central gallery where electricity has to be used. And at TWMA they know how to use it—with care, so not to destroy the integrity of the works. The positioning and strength of the lights illuminating the barks hanging on white walls have been sensitively thought-out: subtle, yet highlighting the natural qualities of the works.

As usual, I walked away from the TarraWarra Museum of Art, not only with a lighter step, but also with a feeling of enlightenment. These organic bark paintings, created by two extraordinary aboriginal artists from Arnhem Land, reinforce the urgency to protect and respect the earth we walk upon, and to treasure the sparkling celestial bodies that we see, and perceive, in the night sky.

JOHN MAWURNDJUL AND GULUMBU YUNUPINGU: Earth and Sky

until 8 June 2015

(Featured image: John Mawurndjul, ‘Billabong at Milmilngkan’, 2009, natural earth pigments on bark, 183.5 x 77 cm)

‘Earth and Sky’ connects through to the North Gallery and ‘Phase Change’, a working design laboratory led by design academics and students from RMIT focused on the changing nature of the environment in relation to TarraWarra Museum of Art and the TarraWarra Estate and Yarra Valley. The public is invited to engage with the participants, and there will be a feedback system, of the students’ invention, that will invite comments. The laboratory will culminate in a public forum on Sunday 31 May from 12 noon to 5 pm, where the participants and invited speakers from the fields of sustainable design, economics and Indigenous knowledge will debate issues highlighted by the project.

There is another exhibition—An-Li: A Chinese Ghost Tale—in the first TWMA gallery space, which follows through with a shared, if thinly disguised, aquatic theme across the three exhibitions. Anthony Fitzpatrick has intelligently curated a new body of work by artist Kate Benyon (Hong Kong born, Melbourne-based; third on the left in the photo above) inspired by the supernatural Chinese story of two young lovers who inhabit both aquatic and earthly realms. The visitor is invited into an ethereal domain featuring an exquisite series of works on paper in watercolour and gouache, paintings in acrylic on linen, and a large-scale suspended sculptural installation made up of 99 cotton calico objects (hands, skulls, fish, oranges, buds, leaves, hearts and eyes). There is also an animated multi-channel video projection of the art works playing in a dark room to the side.

KATE BEYNON: An-Li: A Chinese Ghost Tale

until 8 June 2015

I did enjoy your comments on the Yunupingu,Mawurndjul paintings. They give a good sense of the essence of these works: achieved by how they are painted and how they are informed by their context and so, how important this is in understanding and appreciating them. They are such fabulous paintings. I have an early print by Yunupingu, so direct conceptually and also beautiful and unlike many artworks, still ‘holds me’ in its power after about 10 years having it on my wall.

Thanks.

Thank you Liz. Yes, fabulous bark paintings. How lovely for you to have a Yunupingu print on your wall to admire for so long.