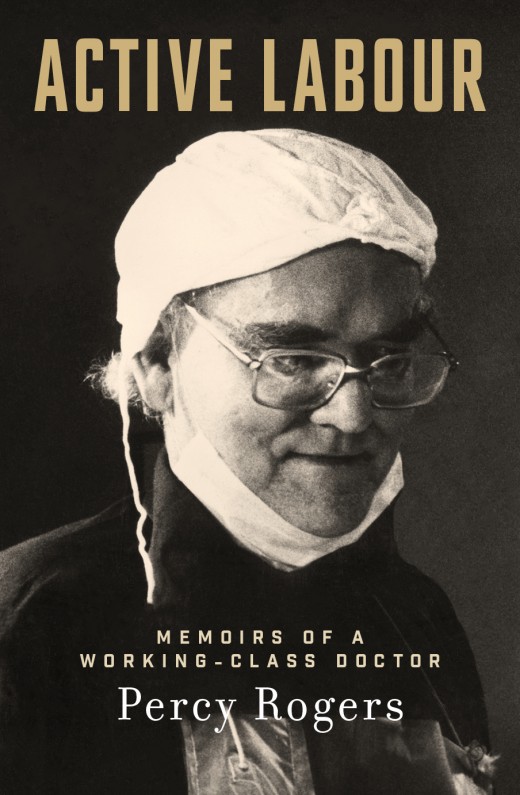

Face masks of dough, wire and the Australian flag; portraits of royalty dripping with black paint; veils, dots and paper cut-outs masking memory and identity; videos hinting at masked abuses in Australia’s history—these are a few of the contemporary art works by approximately 20 Australian artists on display at the TarraWarra Museum of Art (TWMA) Biennial 2014 exhibition, ‘Whisper in my Mask’—a clever take on a line from Grace Jones’ 1981 song ‘Art Groupie’:

Touch Me in a Picture,

Wrap Me in a Cast,

Kiss Me in a Sculpture,

Whisper in My Mask

As Deborah Cheetham AO pointed out in her remarks at the opening of the exhibition on August 15th, the mist that most of us encountered across the indigenous landscape of the Yarra Valley on our way to TWMA was a fitting prelude for the exploration of masks that we were about to experience. What lies behind the mask? In consideration of the bigger picture, Deborah suggested that our nation has many masks that prevent us from fully knowing each other: a smokescreen perhaps?

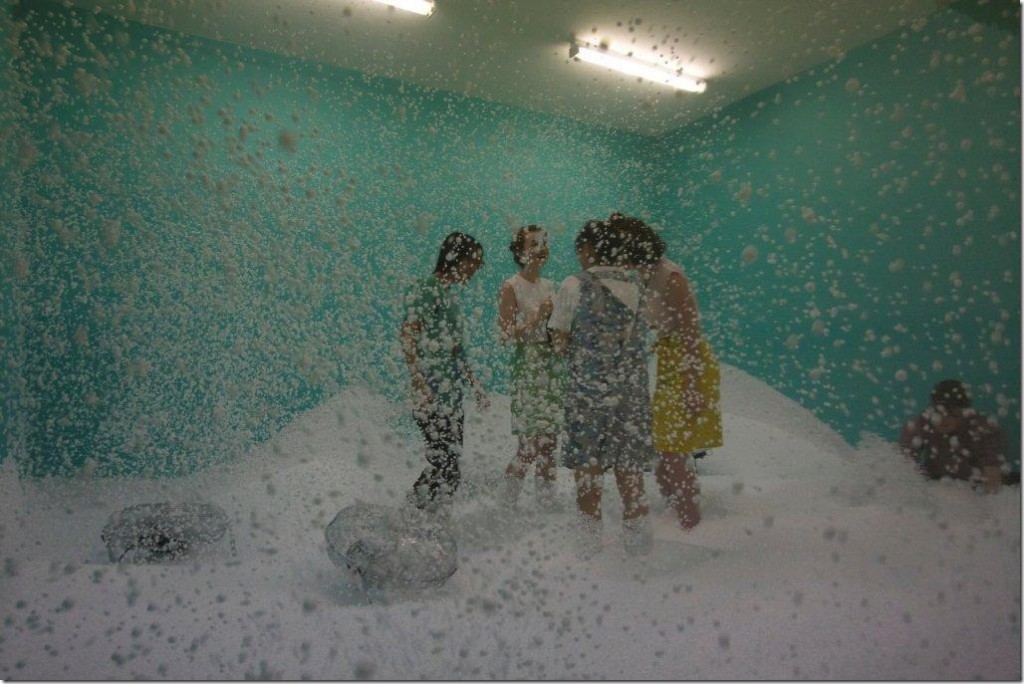

Elizabeth Pedler, ‘Smokescreen’, 2013-14, styrofoam beans, fans, paint, electricity supply, wood, PVC plastic, construction materials, dimensions variable, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Elizabeth Pedler.

The first room of this exhibition is exciting because it immediately stimulates the visitors’ senses and their thinking about masks and masking. Elizabeth Pedler (born 1988) is an emerging Western Australian artist, and her playful experiential installation, ‘Smokescreen’ (2013-2014), with its 3,500 litres of beanbag beans, is installed in an enclosed corner with windows to view the fan-forced beans swirling around those who choose to enter. This interactive work of escapist fun can also be linked to more sinister issues of conscious and sub-conscious, national and personal cover-ups: the intangible mask.

‘Whisper in Your Mask’ is a collaborative curatorial effort between non-Indigenous curator Natalie King and acclaimed Aboriginal curator Djon Mundine, both of whom have enviable CVs and well qualified to ensure that this Biennial has snared cutting edge works by emerging and established Australian artists. King and Mundine wrote in the catalogue that “the mask in its multifarious forms and functions can both reveal and conceal personalities”—this is immediately evident in the first room.

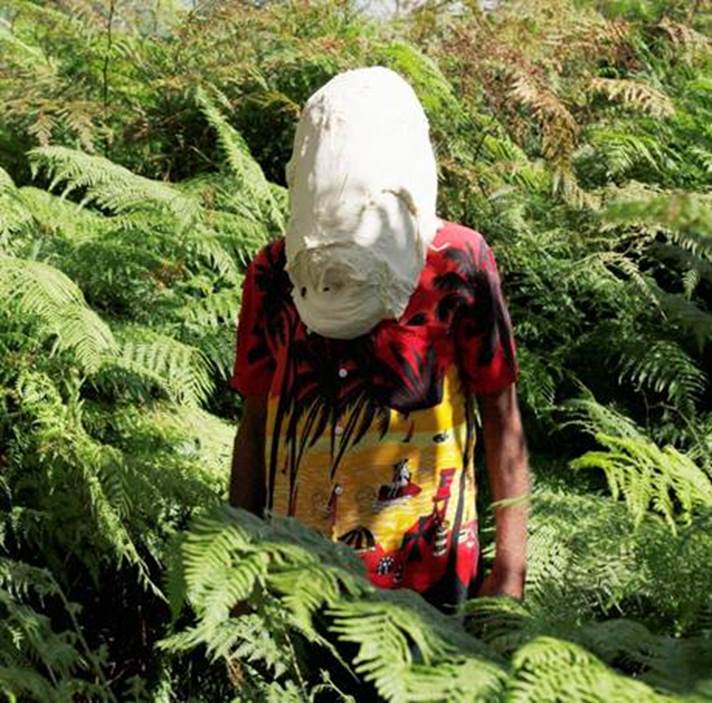

The concept of the cover-up can be applied to the series of ‘Dough Portraits’ (2014) by artist Søren Dahlgaard (born Copenhagen, Denmark, 1973; now lives in Melbourne). The curators explain that the bread dough placed on the head of the sitter is “both a gesture of obliteration and a sculptural cast that is completely absurd”. These ‘portraits’ explore the notion of concealment, giving new meaning to portraiture. The large photograph shown above is hanging adjacent to a wall covered with smaller photographs of these ‘dough’ portraits, all attached to the wall with dressmaking pins.

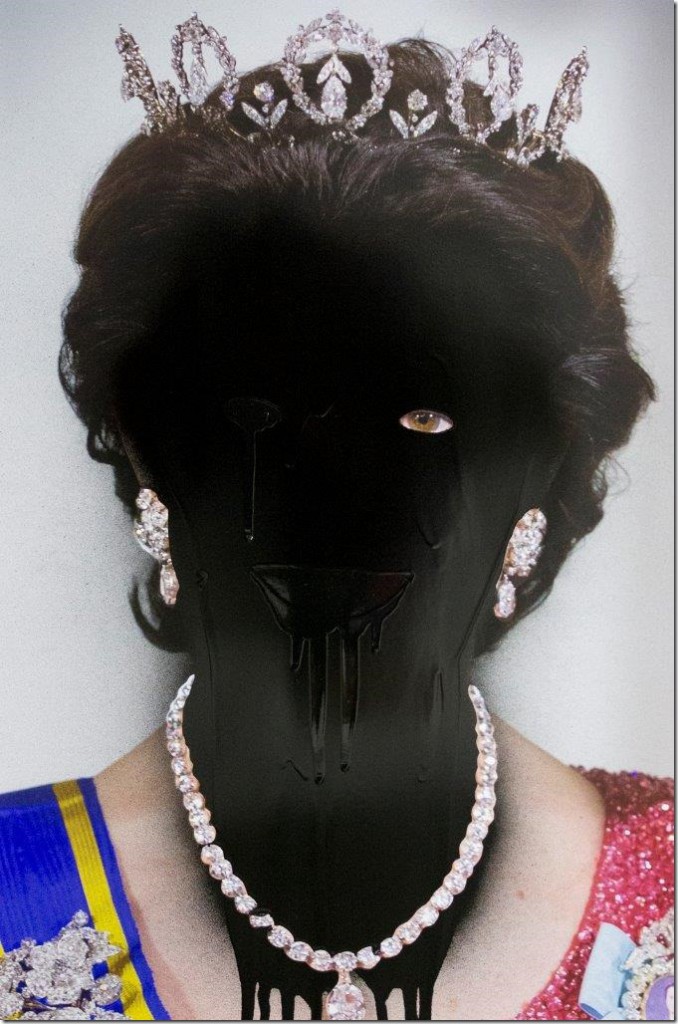

Further along the wall in the first room is Tony Garfalakis’ confronting series of portraits, ‘Bloodlines’ (2014), hung horizontally along a strip of flocked wallpaper: black paint masks most of the faces and identities of European royalty. Many may find these ‘portraits’ amusing, but on a deeper level they reference the ‘invisible’ masks that crowned queens and kings wear to hide long histories of corrupt power. Garfalakis’ art practice brings to our attention the invasive nature of institutions. On the opposite wall are fabric banners by Garfalakis (born 1964), ‘The Hills Have Eyes’ (featured image: Tony Garifalakis, The Hills Have Eyes (detail), 2012, fabric collage, courtesy of the artist) and are well described in the catalogue as “camouflage wall hangings with ominous eyes”. The eyes engage the viewer directly with secret narratives that relate to “military and government surveillance”.

Tony Garifalakis, ‘Untitled’, the ‘Bloodline’ series, 2014, enamel on C type print, 60 x 40 cm, courtesy of the artist.

In a dark room next to Pedler’s ‘Smokescreen’ installation, a 13 minute digital video Vexed, 2013, by Aboriginal artist Fiona Foley (born 1964) reflects upon the masking of the reprehensible theft of Aboriginal women by white men during Australia’s colonisation and how this destructive practice interfered with traditional kinship structures. This film resonates with melancholy and the silence is only broken by the narrator and the screeching of black cockatoos. The breath of masked social histories is felt throughout this exhibition.

Standing in this first room, the viewer’s eye is drawn right through the Museum to the large window at the end, which overlooks the fertile Yarra Valley. TWMA curators often make use of the natural light that streams through this window to enhance specific works, but in this exhibition the window is used to magnify and emulate an element of Daniel Boyd’s signature motif in his paintings: pixilated dots.

Standing in this first room, the viewer’s eye is drawn right through the Museum to the large window at the end, which overlooks the fertile Yarra Valley. TWMA curators often make use of the natural light that streams through this window to enhance specific works, but in this exhibition the window is used to magnify and emulate an element of Daniel Boyd’s signature motif in his paintings: pixilated dots.

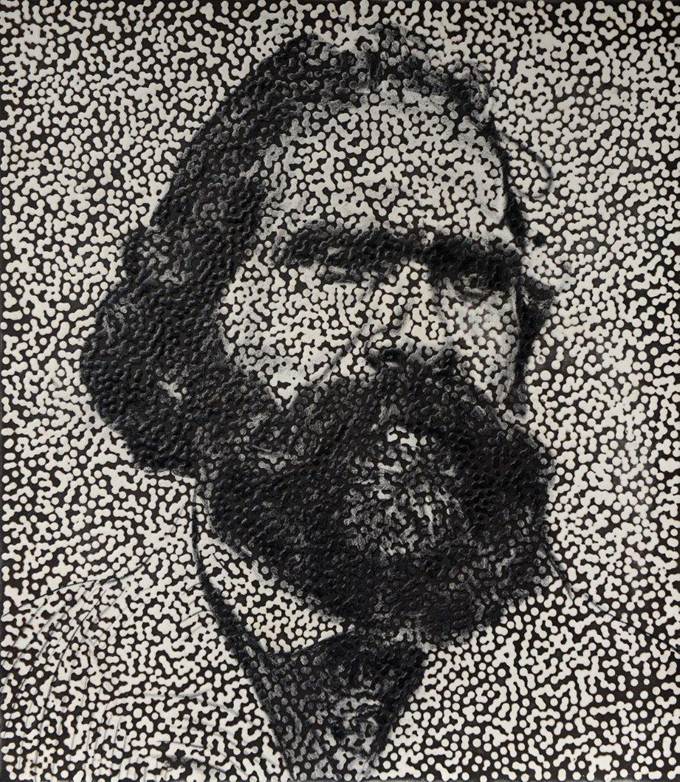

Holes cut out of a black background cover the window, effectively distorting the view of the landscape and challenging the viewer to ‘see’ beyond the visible. Boyd (born 1982) is an Aboriginal artist whose works are overlaid with clear resin dots, intended to confuse, or mask, any attempt at identifying the image or narrative that often explores the veiled history of Indigenous Australians following white settlement and the difficulties associated with assimilation. In many of his paintings he incorporates photographs of his own family. The ‘pixilated’ painting below, which masks the identity of the person, is a fine example of Boyd’s evocative work.

Daniel Boyd, ‘Untitled’, 2014, oil, charcoal and archival glue on canvas, 81.5 x 71 cm, courtesy of STATION, Melbourne.

In this sunlit room at the end of the gallery, woven works by the Tjanpi Desert Weavers collective (formed in 1995 by Indigenous women from Central Australia) are scattered across the floor space. Delightful sculptural forms of Australian animals currently threatened with extinction (such as the rufous hare wallaby, bilby, numbat, western quoll and echidna) have been woven from grass (tjanpi) and emu feathers. There are also bodily forms of introduced species that have had a devastating effect on native animals (such as feral cats). This project was commissioned for the TarraWarra Biennial and partnered by Australian artist, Fiona Hall (born 1953), who worked alongside 12 women from the collective in June this year at a desert camp near Pilakatilyuru about 30kms from the community of Wingellina in Western Australia, just over the border from South Australia in the Ngaanyatjarra Lands. They produced these woven works that demonstrate the positive and negative aspects of disguise and camouflage.

Fiona Hall and the Tjanpi artists with their work at the end of camp, 2014, Photo: Jo Foster, © Tjanpi Desert Weavers, NPY Women’s Council.

The large central room is dominated by sculpted letters forming two words, BLACK VELVET. Positioned on the floor, the wood and metal artwork was created this year by Fiona Foley in association with Urban Art Projects; the sexist and racist connotations relate to the ongoing reality of Indigenous dispossession and displacement. By contrast, the striking colours and high definition photographs of Polixeni Papapetrou’s creepy clowns in various costumes and poses (seven large photographs, which are intended to convey seven stages of grieving) dominate the long wall. Papapetrou (born 1960) is interested in the image of “the clown as mask” and the concealing and revealing of emotion. These photographs reinforce my perception that clowns mask a menacing melancholy, which goes some way to explain my lifelong aversion to clowns.

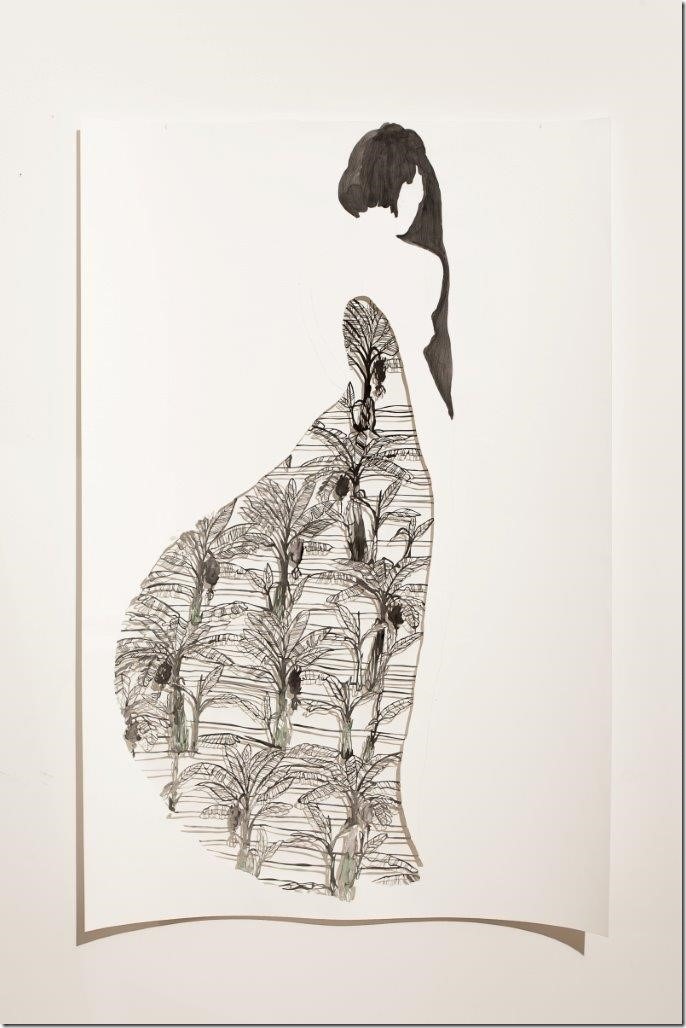

Sangeeta Sandrasegar, ‘I listen for you 9’, 2014, cut paper and watercolour, approx. 150 x 100 cm each, Photo: Ari Hatzis, courtesy of the artist and Murray White Room, Melbourne.

Sangeeta Sandrasegar (born 1977; Malaysian/Australian parents) explores memory and questions identity in her series of delicate paper works, ‘I listen for you’. Her cut-outs, featuring female ghosts, create shadows suggesting alternate personas and lingering memories that ‘whisper’ haunting narratives and folklores to the viewer. As King and Mundine write in the catalogue: “There are a myriad of masks and disguises that sneak up on us, to whisper to us seductively.”

This gem of a museum is not only a shrine to modern and contemporary art made by Australians, but it is a shining beacon that beams out its strong spirit of collaboration with the local area and its people. In other words, it is a museum that sits comfortably within its environment, committed to presenting exhibitions and public programs with themes that challenge the public.

The TWMA Biennial 2014, Whisper in My Mask, runs until November 16.

On October 19 the Museum will hold a special day of events curated for Melbourne Festival, Whisper in My Mask: A day in the valley, featuring Søren Dahlgaard; The Telepathy Project libretto Reading Solaris to the Great Moorool; artists of the TarraWarra Biennial 2014 in conversation with curator Natalie King; poetry readings by Romaine Moreton and A Special Conversation: Henry Reynolds, Djon Mundine & Fiona Foley.

My thanks to Dr Katrina Grant, editor of Melbourne Art Network, for posting this review on the MAN site.