As I wing over to London I think back on the whirlwind that was New York. For 10 days I criss-crossed Manhattan, visiting different areas each day, observing the art that is unique to each area: Greenwich Village, SoHo, Little Italy, Chelsea, Battery Park, Central Park, Uptown, Midtown, Downtown, East Side and West Side . . . I have already written about memorials; this time I reflect upon four museums/exhibitions that stick in my mind . . .

1. Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

Hats off to MoMA! This is a thoroughly modern art museum in every sense. The flat, clean façade integrates almost seamlessly with the glass-fronted commercial buildings sharing space along Manhattan’s West 53rd Street (just south of Central Park near the Rockefeller Centre). This is a welcome change from those temple-like neo-classical museum buildings of yester-year, such as the Met, with their steep ascending stone steps leading up to porticos and doors that open into a cavernous, imposing foyer. Yes, MoMA (completed in 1939 and renovated a few times since) maintains the venerable, oft-criticised ‘white cube’ exhibition space, but why not stick to a good thing if it works—and it does here because white neutrality emphasises the essential formal qualities of modern painting and sculpture. The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum breaks the pure elements of the white cube by using a continuous white ramp to display the majority of its art. This architectural innovation is distracting, and, by the time you get to the top of the spiral, it all becomes one big yawn. On the other hand, MoMA’s paintings are hung at spacious intervals—nothing distracts attention from the works of art, providing a more focussed, and personal, viewing experience. Vistas within MoMA add a lightness and open feeling as visitors can view other galleries and the ground floor from various openings and balconies.

Hats off to MoMA! This is a thoroughly modern art museum in every sense. The flat, clean façade integrates almost seamlessly with the glass-fronted commercial buildings sharing space along Manhattan’s West 53rd Street (just south of Central Park near the Rockefeller Centre). This is a welcome change from those temple-like neo-classical museum buildings of yester-year, such as the Met, with their steep ascending stone steps leading up to porticos and doors that open into a cavernous, imposing foyer. Yes, MoMA (completed in 1939 and renovated a few times since) maintains the venerable, oft-criticised ‘white cube’ exhibition space, but why not stick to a good thing if it works—and it does here because white neutrality emphasises the essential formal qualities of modern painting and sculpture. The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum breaks the pure elements of the white cube by using a continuous white ramp to display the majority of its art. This architectural innovation is distracting, and, by the time you get to the top of the spiral, it all becomes one big yawn. On the other hand, MoMA’s paintings are hung at spacious intervals—nothing distracts attention from the works of art, providing a more focussed, and personal, viewing experience. Vistas within MoMA add a lightness and open feeling as visitors can view other galleries and the ground floor from various openings and balconies.

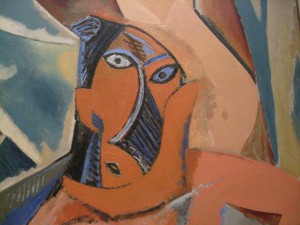

If I had to pick one art work that was a highlight for me at MoMA it would be Pablo Picasso’s fragmented nudes in his ground-breaking painting, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907; detail shown). At the time it was painted, this large work of art challenged traditional, representational painting. Perfectly illuminated, it hangs majestically on a white wall.

2. ‘City as Canvas’, Museum of the City of New York

The 1970s in New York was a time when teenagers, armed with aerosol spray paints and indelible markers, engaged in a new form of graffiti writing in the streets and subways: one that emphasised the aesthetics and visibility of their creations. This became a new artistic movement that faced concerted efforts to eradicate the graffiti from public areas as it was considered to be a form of vandalism. In 1973, Elizabeth Baker, editor of Art in America, wrote: “Vandalism? How can you possibly vandalise the subways? Anything those kids do is a great big plus.” I agree!

The 1970s in New York was a time when teenagers, armed with aerosol spray paints and indelible markers, engaged in a new form of graffiti writing in the streets and subways: one that emphasised the aesthetics and visibility of their creations. This became a new artistic movement that faced concerted efforts to eradicate the graffiti from public areas as it was considered to be a form of vandalism. In 1973, Elizabeth Baker, editor of Art in America, wrote: “Vandalism? How can you possibly vandalise the subways? Anything those kids do is a great big plus.” I agree!

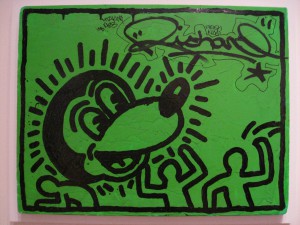

Interestingly, the graffiti art on display in this exhibition, City as Canvas, is owned by the Museum of the City of New York, thanks to the bequest of Martin Wong (1946-1999), who collected these young graffiti artists’ work and helped support them. Keith Haring’s graffiti features in the exhibition including the one shown here (Untitled, 1982). Haring became interested in the graffiti writing movement when he came to New York City in 1978 and began working with the teenager artists. More than any other graffiti artist, Haring enjoyed both national and international recognition; he died from an AIDS-related illness in 1990. Wong succumbed to the same illness in 1999.

Wong requested that his collection be kept intact. Thankfully the Museum recognised the value of this powerful—albeit illicit—form of urban self-expression. This exhibition celebrates the generosity of Wong through the works on display, a variety of sketchbooks and works on canvases and other media created between 1971 and 1992: a lively and interesting window into the evolution of the graffiti writing movement in New York City.

3. The Pre-Raphaelite Legacy: British Art and Design, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This small exhibition at the Met brings together around thirty objects from various departments in the Museum, and from local private collections, to highlight the art of the so-called second generation of the British Pre-Raphaelite artists led by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1822-1889). This bohemian artist and poet mentored other key artists including Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris during the mid to late nineteenth century. Their focus moved away from naturalism towards aestheticism, and poetic and mythical themes.

This small exhibition at the Met brings together around thirty objects from various departments in the Museum, and from local private collections, to highlight the art of the so-called second generation of the British Pre-Raphaelite artists led by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1822-1889). This bohemian artist and poet mentored other key artists including Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris during the mid to late nineteenth century. Their focus moved away from naturalism towards aestheticism, and poetic and mythical themes.

One of the featured paintings by Burne-Jones, The Love Song, (1868-77), shows the early Pre-Raphaelite interest in medievalism merging into the softly glowing world of a Venetian Renaissance painting. The result is a dreamy scene of a knight enraptured by the women draped in Botticelli-like garments (one of them is shown here in the detail), and the song they are performing with the accompaniment of a harp; music, chivalry and mythical beings in an idyllic landscape. Later, Rossetti moved away from narrative and became more interested in aestheticism and painting portraits of beautiful women.

As can be seen in this exhibition, the art of the Rossetti circle extended across a range of media including paintings, drawings, furniture, ceramics, stained glass, textiles, and book illustrations. The enduring impact of Pre-Raphaelite ideals were adapted by different artists and designers such as William de Morgan (1839-1917), who began his career painting stained glass for William Morris’ company. The earthernware charger on display, with its fish swimming through a leafy pond, is enhanced by the red and yellow lustered glaze. Although the design is known to be influenced by fifteenth-century Hispano-Moresque wares, this surely was inspired by William Morris’ unique and intricate decorative designs that culminated in the Arts and Crafts movement.

4. Body Worlds: Pulse, Discovery Centre, Times Square.

Gunther von Hagens’ human anatomy exhibition, Body Worlds: Pulse, now in New York, is advertised as an “exhibit about you and the beat of life”. On entry, the visitor views an animated video about the pace of life and its ill-effects on our health; then the first dead body, set in an active pose, is displayed in a glass case. It is made clear that these models are “real”, and that they have all “freely” bequeathed their bodies to be plastinated and used in this exhibition.

Gunther von Hagens’ human anatomy exhibition, Body Worlds: Pulse, now in New York, is advertised as an “exhibit about you and the beat of life”. On entry, the visitor views an animated video about the pace of life and its ill-effects on our health; then the first dead body, set in an active pose, is displayed in a glass case. It is made clear that these models are “real”, and that they have all “freely” bequeathed their bodies to be plastinated and used in this exhibition.

These dead, inorganic human bodies ‘come alive’ as visitors circle around them and navigate between them—they are a work of art. There is science to consider too: body ‘bits’ are displayed showing the effects of diseases and unhealthy lifestyles such as smoking. Interesting? Educational? Maybe, but to my mind, the workings of the body are explained much better with digitally enhanced artificial models.

As you can imagine, Body Worlds has generated much discussion about how human remains should be treated. Who displays the dead, and should they be contorted into various poses? This complex, philosophical issue extends to the display of human remains removed from ancient Egyptian tombs, ignoring the burial wishes of those entombed. And what about the display of the Iron Age Lindow ‘bog man’, who has been dug up from his grave? There arises a range of overlapping and often conflicting concerns, but as long as the curiosity of the visiting public continues, from the detached scientific type to the morbid through to the fascinated, it is likely that museums will justify the display of these dead bodies. Indeed, Body Worlds has attracted in excess of 25 million visits worldwide across more than 40 cities since its inauguration in 1995. Those who support this display of dead people argue that exhibits of human remains are just exhibits of humans, shown to be mortal: it is simply Death.

***

The featured image is Jasper John’s iconic artwork, Flag (1954-55, MoMA), a collage on fabric that includes newspaper scraps under the surface of paint. The picture complicates the representation of the American flag.