This ingenious exhibition, ‘Edward Steichen & Art Deco Fashion’, combining the innovative photography of Edward Steichen (1879-1973) and a stunning selection of 1920s and 1930s garments and accessories from the National Gallery of Victoria’s collection, is sure to impress. Behind the camera, Steichen captured the personalities of Hollywood and the elegance of the modern woman dressed to reflect post-war exuberance. According to fashion curator, Paola Di Trocchio, this was the only time in fashion history when women led the major fashion houses of Europe; consequently, women were liberated from bustles and corsets. It is perhaps no exaggeration that modern fashion photography began with Edward Steichen—and that the template for the modern wardrobe was established in the Art Deco period.

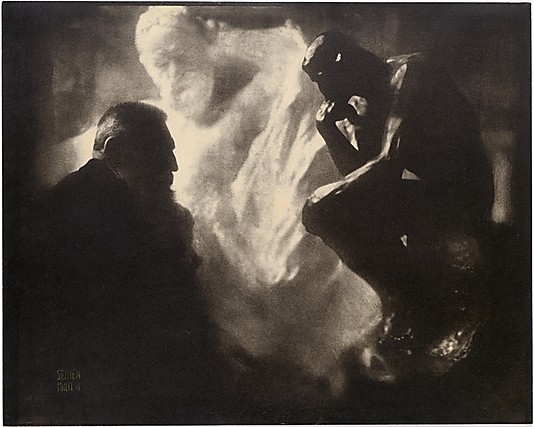

First, some background on Edward Steichen: born in Luxembourg in 1879, his family moved to Michigan in the U.S. when he was two; as young man, Steichen honed his craft as a photographer, lithographer and painter. In 1900 Steichen sailed to Europe and developed an innovative style that drew fire from purists in the photographic community in Paris and London. Steichen’s invention is attributed to his command of light and shade, which at first, prior to WW1, was soft and atmospheric. His 1902 photograph, Rodin—The Thinker, is Steichen’s tribute to the genius of avant-garde French sculptor, Auguste Rodin (1840-1917). The image is suggestive of the joining of brush and lens into a seamless pictorial language: Rodin sits before his famous sculpture, ‘The Thinker’, with the white monument of French writer and poet, Victor Hugo, in the background.

Returning to New York in 1902, Steichen joined Alfred Stieglitz’s band of Pictorialists (photography beyond the realm of pure documentation) and Photo-Secessionists (photography as a creative non-commercial practice); they argued that photography should be regarded as fine art. Steiglitz’s circle was the international coterie of artists and writers who made up the West’s intellectual counterculture. Between 1903 and 1917 Steichen became the most frequently featured photographer in Stieglitz’s ground-breaking photography magazine, Camera Work. Following WW1, Steichen painted and experimented with photography focussing on a hard-edge style, abstracting his subjects and working with stark tonal contrasts. Between 1923 and 1938, Steichen was chief photographer for New York’s most influential and glamorous magazines: Vanity Fair and Vogue. Condé Montrose Nast, dress-pattern tycoon and owner of the magazines, assigned fashion to Vogue and Vanity Fair featured screen idol portraits. During Steichen’s 13 years with Condé Nast he also created advertising images for the J. Walter Thompson agency. Steichen’s innovative work secured his future as one of the most highly paid fashion photographers in the world (Steiglitz called him a “sell-out”).

Gabrielle Chanel (designer), ‘Dress’, 1924, silk, glass beads, National Gallery of Victoria curators Paola Di Trocchio (right) and Susan Van Wyk. Photo: Simon Schluter.

And so the exhibition begins . . . with ‘Coco’ Chanel’s ‘little black dress’. Although French designer, Gabrielle Chanel (1883-1971) did not champion feminism, she liberated women’s fashion in the 1920s and 30s by discarding the corset and raising the hemline. In other words, Chanel designed clothing that allowed women to move more freely. The Chanel ‘little black dress’ (1924) is the first costume on display as one enters the exhibition. The black silk art-deco dress decorated with glass beads and ribbon was acquired by the NGV through a London auctioneer in January this year. This simple dress that slipped over the head made black chic, transforming its traditional association with grief and mourning into a symbol of independence and power for women. As Di Trocchio tells us, Chanel’s ‘little black dress’ was “emblematic for its simplicity, seduction, practicality, and modernity”.

There are two 1924 Steichen photographs of Chanel dresses on the wall across from the ‘little black dress’, one with actress turned model, and Steichen’s muse for many years, Marion Morehouse, wearing a Chanel evening gown. The soft focus of Steichen’s early photographs can be seen here. Already I was hoping (alas) that visitors could see at least one enlarged Steichen photograph. However, between the two exhibition rooms, there is a wonderful silent film of a temperamental Steichen conducting a photo shoot—a chance to sit and gain some understanding of this creative man.

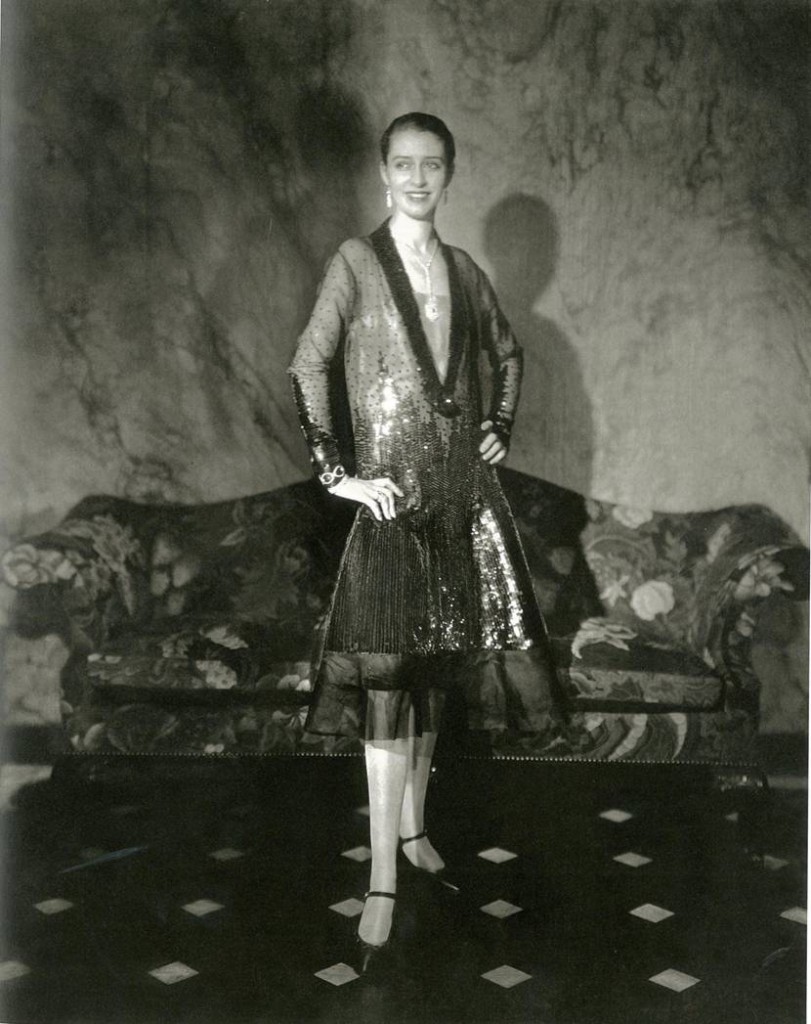

The flat, stylised motifs and geometric angles synonymous with the Art Deco style of the 1920s and 30s transformed fashion, and Steichen developed a sharper focus from about 1927. His new style not only reflected the machine age and art deco architecture, but also signified the increasing confidence of the new woman to express her individuality. As such, Steichen is credited with introducing this modern woman through his photographs. One of these most memorable images is that of Marion Morehouse wearing a daring sequined ‘flapper’ dress, posing with hands on hips and reflecting her vibrant personality. In Steichen’s spotlight, Morehouse’s natural, broad smile shines with as much intensity as the glitter on her frock (1927; image below).

Paolo Di Trocchio describes the ‘flapper’ in the exhibition catalogue as:

a term used to describe highly social, reckless, carefree and independent young women of the era … these dresses, with their artfully applied sequins, their reflective surfaces and their adoption for dances such as the Charleston and the Black Bottom, encouraged the impression of freedom and flight.

The short 1927 black dance dress (French, image left) on display near the photograph of Morehouse is similar to the flapper dress she is wearing. Stylised flowers are sewn on the hipline and one can imagine the sequined skirt enlivened by movement and light during dancing. Nearby, the tangerine-coloured 1924 Evening Dress by French designer, Madeleine Vionnet (1876-1975) is longer but still perfect for dancing. The tear-shaped scallops (each scallop features a stylised rose in metallic thread) increase in size down the dress resulting in greater fullness towards the hem; a wide neckline frees the dress from buttons and hooks, and the separate lining allowed the silk tulle dress to move independently.

Loose-fitting coats by French designers, Jeanne Lanvin and Jeanne Paquin, reflect the influence of the Russian Ballet Russes and the Orient: Japanese kimonos and the flat forms of ukiyo-e woodblock prints, and Chinese ceremonial robes with elaborate embroidery. Lanvin’s Coat (1926) has the shape of a kimono, with rounded shoulders, a collarless neckline, an open front and loose sleeves.

Don’t miss the accessories for the 1920s woman on the go: the head-hugging cloche hats that suited women with cropped hair (the ‘bob’), the shoes that set off the short flapper dress, and the jazzy bags to complement the outfit.

Edward Steichen excelled in the field of portraiture for Vanity Fair (established in New York one hundred years ago) due to his direct engagement with the sitter, and being able to capture the personalities and essence of his celebrity models. He photographed filmmakers such as Cecil B. De Mille and Josef von Sternberg; suave actors such as Gary Cooper (looking like the prototype for Jon Hamm’s Don Draper in the hit TV series, Mad Men); writers W.B. Yeats and Colette; dancers Martha Graham and Fred Astaire; musicians such as George Gershwin. Steichen’s photograph of pale-eyed actress Gloria Swanson makes use of a black lace veil—she looks like a “tiger moth in a lace cage” or, as Steichen reminisced: “a leopardess lurking behind leafy shrubbery, watching her prey”. Most of the models stare directly at the camera.

During the Art Deco era outdoor leisure activities became popular and women were more involved in sports such as swimming, golf and tennis. Physical fitness and sunbathing became fashionable and tourism boomed. This exhibition displays one of those daring 1920s one-piece tank-style top bathing suits with elasticated ribbed knits. Steichen captured the sportswoman in action.

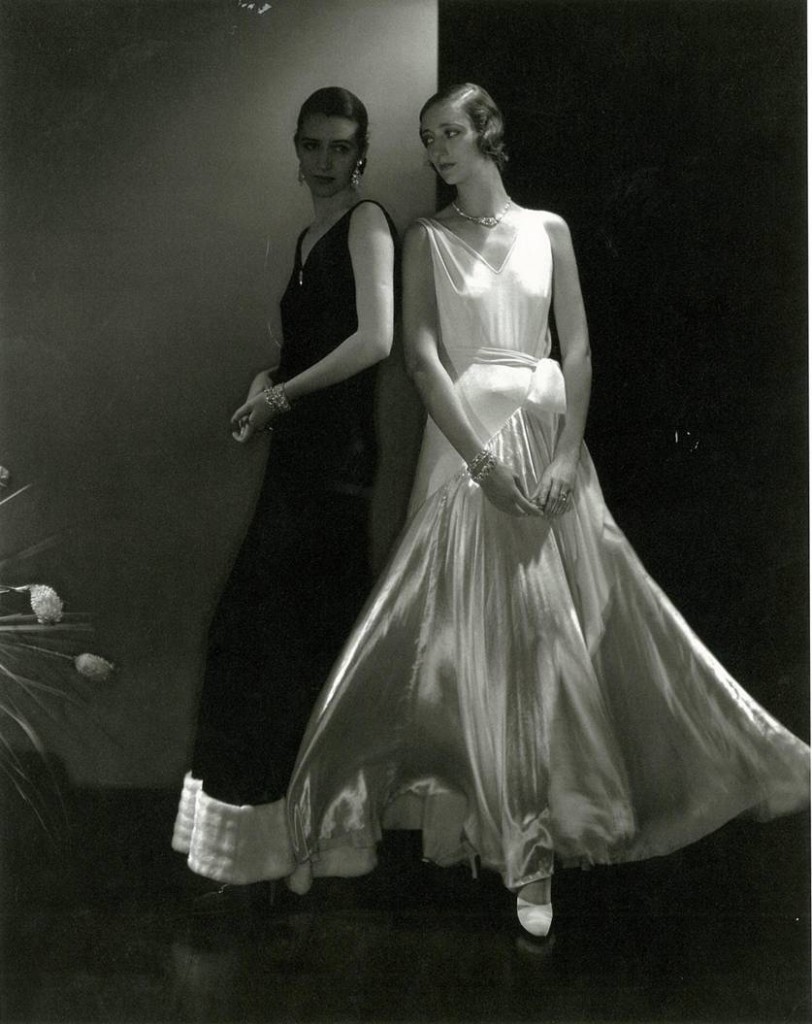

After the Wall Street stock market crash in 1929, the ‘flapper’ look quickly disappeared and hems came down to reflect the downturn in the economy. Fashion reverted to a more feminine figure-hugging silhouette, and backless evening dresses satisfied the Hay censorship code. Comfort was still an essential design element, but there were less geometric motifs; instead, stripes, soft frills and florals became popular. Using light as his brush, Steichen accentuated the drapery and shimmering effects of the silk, satin and velvet gowns created by designers such as Vionnet, who was labelled the ‘queen of the bias-cut’ (bias-cut: fabric cut diagonal to the grain to enhance its stretch and allows the fabric to cling to the body while moving with the wearer). Vionnet the fashion designer and Morehouse the model were Steichen favourites; the Vionnet 1930 bias-cut evening dresses and the brilliance of Steichen the photographer come together in the striking photograph below (Morehouse is in shadow wearing black).

As soon as the visitor walks into the first of the two rooms of this exhibition the seductiveness of the Art Deco style comes to life: chevron mirrors, softly ruched curtains, models with attitude. The NGV has an exquisite fashion and textiles collection and this idea of combining Steichen’s photographs of high profile personalities with garments and accessories from the Art Deco era in one exhibition is inspirational. But this exhibition is not just about fashion and photographs: it reveals the underbelly of American and European culture between two world wars, when glamour and modernity dovetailed to light a torch for women’s liberation, pave the way for leisure pursuits, and a more exotic way of life.

Until 2 March 2014

NGV International, 180 St Kilda Road, Melbourne

Ground level

Daily except Tuesdays: 10am-5pm

Guided tours: Wednesdays and Sundays at 1.30 pm (free)

Photography:

Edward Steichen fashion photographs are courtesy Condé Nast Archive © Condé Nast Publications

NGV photographs of garments: Narelle Wilson