Claude Monet, ‘The bridge over the waterlily pond’, 1900, oil on canvas, 89.8 x 101.0 cm, Art Institute Chicago, Illinois.

Claude Monet (1846-1926) painted water in its many forms and moods—a rough and animated sea, a misty and mysterious river, a still and reflective pond, and crisp, white snow. Monet began his water garden at his home in Giverny in 1893, and over time the plants in and around the pond grew and merged, softened and framed. In Monet’s painting, The bridge over the waterlily pond (1900), the water’s mirror-like surface reflects the bordering plants and weeping willows. Having stood on that rustic ‘Japanese’ bridge spanning the waterlily pond in his water garden, I can understand Monet’s extensive engagement with the mesmerising effect of peering into the depths of the water beyond the drifting waterlilies.

In April 1883, Monet’s family moved to the village of Giverny (approximately eighty kilometres north-west of Paris), which is situated on an ‘arm’ of the Seine river and surrounded by picturesque meadows, woods and low hills—an ideal environment for an Impressionist painter. Monet rented Le Pressoir (wine press-house), a large pink rough-cast house with grey shutters that were soon to be painted bright green. Standing in a clos normand (traditional walled garden) and comprising flowerbeds, orchards and a vegetable plot, this house was home for Monet and his family for the rest of their lives.

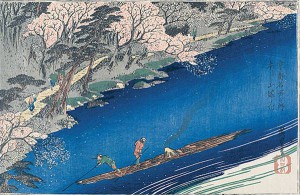

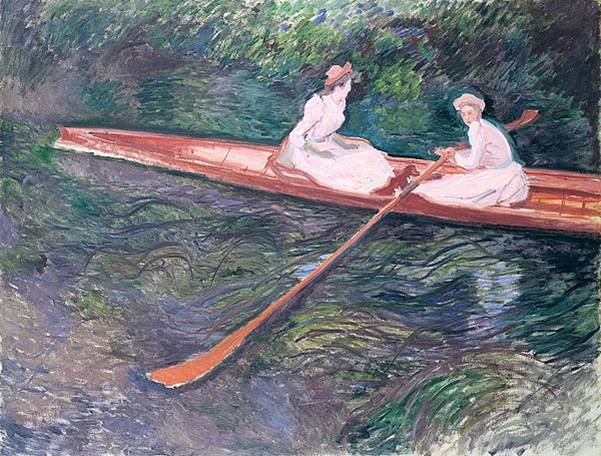

Monet collected Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints and hung them on the walls of his yellow dining room. He particularly liked the landscape prints of Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and his younger contemporary, Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858). Earlier this year, Bendigo Art Gallery’s exhibition, ‘Japanese Visions’, provided an insight into the aesthetics of nineteenth-century ukiyo-e prints and their influence on artists in the Western world. Although there are no ukiyo-e prints on display in the current exhibition, ‘Monet’s Garden’, at the National Gallery of Victoria, there are clear indications that Monet moved towards a more stylistic form of representation and innovative treatment of space through his study of ukiyo-e prints. For example, the high viewpoint and cropping in Hiroshige’s Full Blossom at Arashiyama (c 1834), were emulated in many of Monet’s paintings, such as Pink Skiff (1890), in which the oars project into the viewer’s space and the skiff is cropped. In June 1890 Monet wrote: “I have again taken up things impossible to do: water with grass waving in its depths . . .” Monet’s compositional strategies and dynamic brush marks sought to concentrate the view and express nature’s inner life. He rarely painted the human figure after 1890.

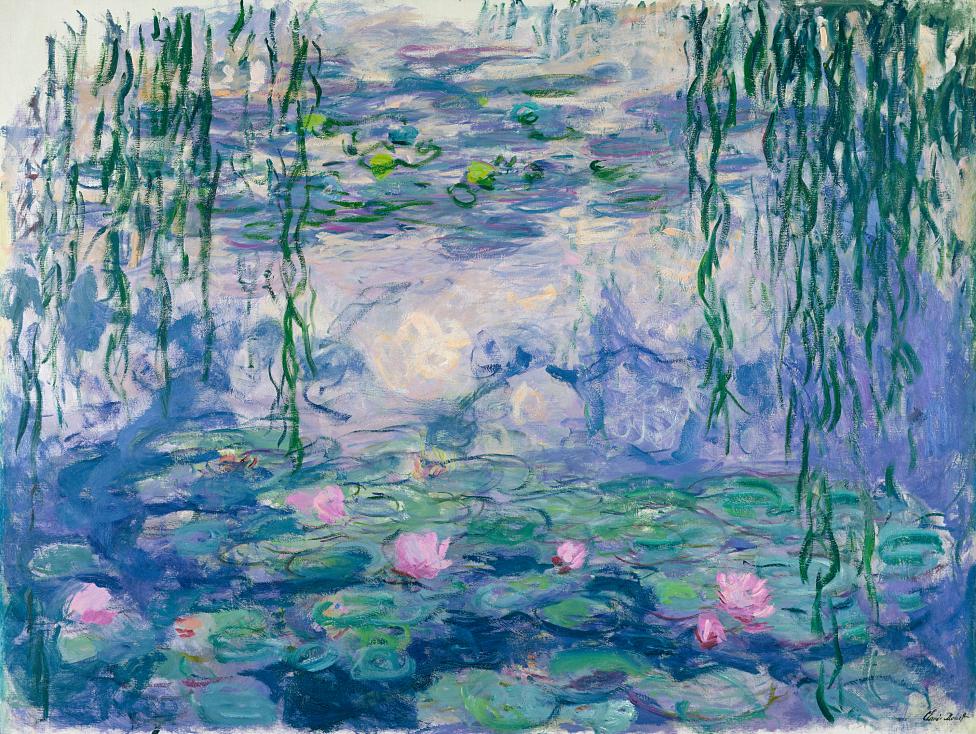

In his later years, Monet often used the Japanese technique of showing a fragment of nature in close-up with no obvious spatial organisation. His waterlily paintings seem to imitate the dynamic linearism and expressive empty space of Japanese screen painting: the eye moves across the horizontal surface using emptiness to suggest the infinite. Monet’s creation of a homogenous, consistent format with unifying brushstrokes makes it difficult to distinguish the expanse of water, the reflections of the surrounding garden, the sky, and the plants below the surface. The result is decorative due to the repetitive rhythms and extension of space. Waterlilies (Nymphéas) —painted between 1916 and 1919—not only signifies this dream-like image of weightless waterlilies floating upon still water, but also exemplifies the end result of the many years Monet spent nurturing his garden, his place of art.

Claude Monet, ‘Waterlilies’ (Nymphéas), 1916–19, oil on canvas, 150.0 x 197.0 cm, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris.

In Christian tradition, the waterlily represented purity and resurrection, opening each day, unaffected by the muddied waters in which it often grew. The waterlily is also connected with the female spirits of classical mythology: the beauty of the water nymphs entranced men to make them their captive in their stagnant watery domain. In Europe during the late nineteenth century, the waterlily became an emblem of the Symbolist movement, signifying femininity, desire and the occult.

In 1896 British artist, John William Waterhouse (1849-1917), painted Hylas and the Nymphs, which exemplifies the Pre-Raphaelite style and the frequent use of symbolism by Pre-Raphaelite artists. Hylas was one of the Argonauts who sailed with Jason in search of the Golden Fleece. During a brief stop on the island of Cios, Hylas’ task was to search for fresh water. He found a pond, and as he was filling his pitcher, the water nymphs emerged from the depths, luring him below the surface . . . Hylas was never seen again. The myth of Hylas drowning amongst the waterlilies came to represent the deadly allure of the femme fatale. In Giverny, Monet was more interested in painting nature as truthfully as he could; however, his waterlily paintings broke with traditional pictorial ideas.

In 1926, Claude Monet’s friend, George Clemenceau (Prime Minister of France 1906-1909/1917-1920), wrote of the beauty of Giverny:

Monet loved flowers . . . for the abundant shafts of soft or vivid colour that so defiantly flaunt themselves amid giant rose trees where those weary of a mundane existence can feast their eyes . . . Therein, to be precise, lies the miracle of the Waterlily paintings which portray things in a way that differs from our prior observation of them: in novel relationships and in a new light, as ever-changing aspects of a universe that is unaware of itself yet self-expressive by way of our own sensations”.

On 10 July 2007 I walked down the narrow walled street in Giverny and entered a gate into Claude Monet’s house and garden. I sat on the steps of his pink and green house soaking up the summer sun with the colours of the garden before me, just as Monet would have done one hundred years ago. Monet planned his garden with the eyes of an artist, and Giverny, his place of art, demands reflection. Today, 1 September 2013, is the first day of spring and new life is emerging throughout my garden: four weeping silver birches are tinged with green, fragile white blossom attach precariously to branches, and the camellia bushes are dropping their pink and white flowers to the ground . . . they look like waterlilies afloat upon a dark pond, but there is no reflection.

****

It is not the intention of this post to review the NGV exhibition, ‘Monet’s Garden’ (closes 8 September 2013); instead I invite you to read the following reviews:

Christopher Allen, ‘A World of Reflection’ (The Australian, 25 May 2013):

“the artist looks down into the water and there is no horizon or sky to relativise this world of reflections and consign it to a secondary status of reality”.

David R. Marshall’s review (Melbourne Art Network) triggers our thinking about “the symbiosis between place-making and art”.