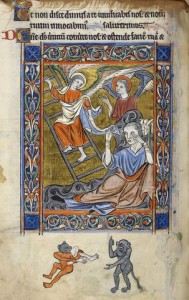

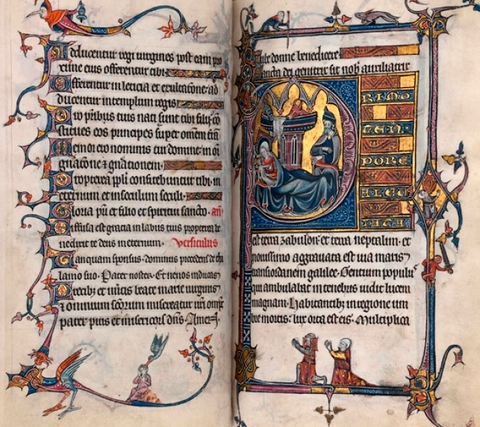

Rutland Psalter (England, c.1260, Latin, Add. MS 62925, British Library), miniature of Jacob’s Ladder, before Psalm 80; bas-de-page scene of cannibal hybrids, f. 83v.

What are those rabbits doing in the border of that medieval prayer book? Is that a snail jousting with a dog? Why is a naked man riding a many-legged ‘dragon’ in the lower margin? No, your eyes are not deceiving you. This profusion of humans, animals, fantastical plants and grotesques painted in the margins of thirteenth and early fourteenth-century Europe manuscripts was common. Collectively, this is called ‘marginalia’ (the Latin word for ‘things in the margin’). Animated border decoration frames the Latin text and larger illustrations on most pages (folios) of Gothic illuminated books. It goes without saying that the frequently humorous marginal scenes are at times confusing and ambiguous. In some cases, the lively marginalia supplements the theme or topic covered in the text or main illustration. In other cases, the relationship between word and image is less obvious. Secular subjects are often depicted in the margins of religious books making fun of the activities of nobility and the clergy, but more broadly, at human weaknesses. Knights, nuns, devils, patrons, saints, dogs, birds, snails, rabbits and monsters colonise the borders with varying degrees of parody and seriousness. In his book, Image on the Edge: the Margins of Medieval Art (2003), Michael Camille writes that, by the end of the thirteenth century, “no text was spared the irreverent explosion of marginal mayhem”.

A Gothic illuminated book of Psalms called the Rutland Psalter* (England, c.1260, Latin, Add. MS 62925, British Library) includes many full- and partial-page illustrations with a fascinating variety of marginalia. The manuscript was purchased by the British Library in 1983 from the estate of the ninth Duke of Rutland, whose family had owned the manuscript since at least 1825. Figures and creatures populate the borders of virtually every folio. Grotesque forms appear on letter and initial extensions, line-endings, and often inhabit the lower margins (bas-de-page). Although the images in the ‘Rutland’ margins appear to be pure fantasy, such as naked or near-naked men or half-men looking up at an ape in a tree, or riding on hybrids and dragons (featured image), they may be symbolic for the medieval reader. However, it is difficult to envisage the book being conducive to private, contemplative devotion because, in most cases, the marginalia of the Rutland Psalter has little or no connection with the Psalm, or reality. The artists’ work in the margins has all the indications of ‘poetic licence’.

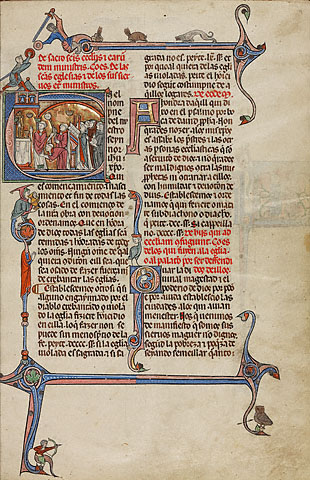

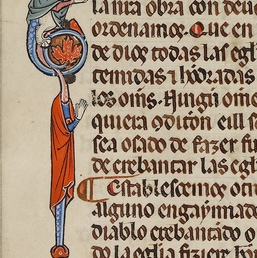

The J. Paul Getty Museum owns an anonymous Spanish manuscript (MS Ludwig XIV, c. 1290-1310) in which folio 9 (image to the left) has an illustration of Mass being solemnly celebrated by a priest and monks within a large initial ‘E’. In the margins, a headless figure is praying (see detail below) and a court jester is drinking; there are bird-men, a dog chasing a rabbit, an archer shooting an arrow at an owl across the page. These absurd ‘drolleries’ add a questionable humour to the page yet there appears to be a strict dividing line between the pious and mad-cap ‘fun’; they never merge.

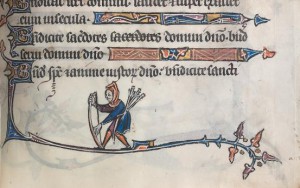

The two-volume Aspremont-Kievraing Psalter-‘Hours’ **(Lorraine, France, c. 1300, Latin, MS Felton 1254-3, National Gallery of Victoria) abounds with lively marginalia that not only provide important cultural indicators of everyday life for men and women, but also the usual array of fantastical creatures. The manuscript is now divided into two parts: the psalter is in the Bodleian Library, Oxford (MS Douce 118), and the volume containing the series of Offices in honour of the Virgin was acquired by the National Gallery of Victoria in 1922. The original patron was the French knight, Joffrey d’Aspremont (who succeeded to the title Aspremont between 1278 and 1282), and his wife, Isabelle de Kievraing. Numerous Aspremont-Kievraing heraldic insignia appear throughout the border decoration, and the knight and his lady are seen at regular intervals in prayer (f. 11; image below) and attending jousting events. The way the patrons have been depicted reflects social conventions, decorum and gender differences during late thirteenth and early fourteenth-century France. Joffrey is frequently portrayed in the margins as a distinguished knight indulging in masculine and aggressive pursuits, such as jousting and hunting. In one border decoration he is seen attending a chapel service, his shield hangs beside him and he is accompanied by his horse! In another margin, a hybrid ape-man ‘knight’ (the ape is popular in Gothic marginalia as a means of exposing human pretentiousness) rides a dog as he jousts with a spindle towards a runaway snail (the snail as a symbol of cowardice was popular). As you can see, parody of nobility and knightly combat is common in medieval manuscripts! Joffrey’s wife, Isabelle is depicted in the domestic sphere, praying and reading, accompanied by amusing animals, birds and grotesques. It appears that the juxtaposition of fantasy and people going about their normal activities in the margins of prayer books was fashionable during this period. Certainly a distraction for the prayerful reader!

Aspremont-Kievraing Psalter-‘Hours’ (Lorraine, France, c. 1300, Latin, MS Felton 1254-3, National Gallery of Victoria), volume II, Nativity scene, ff. 10v-11

Marginalia in medieval illuminated books resonates with a multiplicity of meaning. It is not always completely clear what function these marginal images served, particularly when the misbehaviour of misfits co-exist with religious text. I have only written about art in the margins of these manuscripts; however, marginalia also includes notes, scribblings and comments, something I am guilty of today. In 1844 Edgar Allan Poe wrote: “In getting my books, I have always been solicitous of an ample margin; this is not so much through any love of the thing in itself, however agreeable, as for the facility it affords me of penciling in suggested thoughts, agreements, and differences of opinion, or brief critical comments in general.” Maybe that was the aim of medieval marginalia artists: some sort of symbolic comment based on social and religious conventions but transformed into a carnival world.

*the psalter is the book of the 150 Psalms in the Bible.

**the psalter-hours is a devotional book which is usually a combination of a psalter and a book of hours (a prayer book which takes its name from short offices or hours that were times set aside for religious or business duties).

Professor Margaret Manion introduced me to the world of medieval illuminated books. This article has been written in appreciation of the knowledge she has so freely imparted to her students at The University of Melbourne. I have had access to many wonderful medieval books and manuscripts held in Melbourne at the Baillieu Library, the State Library of Victoria and the National Gallery of Victoria.