Barbara Hepworth’s garden in St Ives, Cornwall, is small and walled, but there are foregrounds and views which are framed by the ‘holes’ that pierce most of her sculptures. This place of art echoes Hepworth’s philosophy as an artist: “to infuse the formal perfection of geometry with the vital grace of nature”. A bird’s-eye view of Barbara’s ‘back-yard’ would be unsatisfactory; you have to experience this garden at ground-level.

English sculptor, Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975), was inspired by nature and the human form. In August 1939, just before the outbreak of war, Barbara moved to Cornwall from London with her husband and painter, Ben Nicholson, and their triplets. The day after she bought Trewyn Studio in St Ives at a public auction in September 1949, Barbara wrote to a friend: “it will be a joy to carve in such a perfect place, both serene & secluded – the courtyard & garden protected by tall trees & roof tops so that I can work out of doors most of the year”. Between 1949 and 1975 Hepworth integrated her sculptures into the garden with considerable energy and vitality; her work resounds with contemplative labour that belies her small frame.

I visited Barbara’s garden on 26 October 2012, an autumn day when an unseasonal arctic wind seemed to pierce right through me; I bonded with many of the pierced humanoid sculptures in this near-deserted garden. Everywhere I turned there were organic sculptural forms with holes through which I could see trees, bamboo, shrubs, flowers and rooftops— abstract sculpture and nature in perfect harmony. One was big enough for me to enter. Inside, I looked up at the sky through a gaping hole as drizzle spattered down onto the bronze floor. These holes or openings are like eyes … caves … windows.

The main photo for this article features Sphere with Inner Form (1963), a bronze cast from a plaster sculpture: one small form encircled by another larger one (common in Hepworth’s work from the 1930s). Barbara was drawn to the ‘nature-nurture’ concept evoked by a protective seashell, a seed pod or a baby growing inside a woman’s uterus. The rose was one of Barbara’s favourite flowers and although the rose bush planted beside Sphere with Inner Form had finished flowering, the unpruned bush with its scarlet seed pods framed the sculpture. A garden undergoes constant change in form and colour, its growth and maintenance requiring physical labour, a perfect backdrop for Barbara Hepworth’s static yet organic sculptures.

Many of Hepworth’s stone, plaster and wood ‘carvings’ have elements of rock-pool, sea caves, sand dunes, curved headlands and bays. She was ‘romantic’ in her emotional response to nature, yet she was fascinated with the ‘forces’ which mould the landscape. Her description of the rugged coastal landscape of Cornwall as “barbaric and magical” is emulated in her 1958 painted plaster model, Sea Form (Porthmeor). I can see waves curling over ancient wind-hewn rocks, perforated by the sea. Barbara spent time at nearby Porthmeor beach watching the waves and the observing nature in all its moods. Seven bronzes have been cast from this Sea Form model.

Born in Yorkshire in 1903, Hepworth trained as a sculptor at Leeds School of Art then at the Royal College of Art, London, between 1920 and 1923. She was closely associated with other artists from Leeds, including Henry Moore. They were recognised as the new breed of abstract artists in England, rediscovering sculpture as manual labour. The art of direct, physical carving was revived, thus allowing the qualities of stone or wood to play a significant role in the creative process. During the 1930s Barbara visited a number of artists in Europe, including Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.

Later in her career Hepworth experimented with the oval shape and the opening of form to light, colour and space. River Form (1965, cast in bronze 1973) is an oval bronze cast from a wood carving. Rain had pooled water into the shallow ‘basin’ which gave the work an ethereal dimension, especially as the interior was painted in an aqua blue with broken brushstrokes. Three holes in the rear of the sculpture allowed a play of light to infiltrate the interior, and again, my vision was drawn through to view the garden beyond. I recalled the 1970s when the idea of sculpture as an intensely carved and crafted object was being questioned by the ‘new breed’ of sculptors. Can anyone remember Gilbert and George when they first performed The Singing Sculpture, posing as self-styled ‘living statues’ and singing ‘Underneath the Arches’?

Peering through the window of her ghostly studio, which stands in the garden, sent a chill through me which had nothing to do with the freezing atmosphere and the drizzling rain. You can see the tools she loved to use: all her chisels, saws and hammers, as well as her white work apron and a set of unfinished pieces. There is a sense of purity; this is a shrine to physical work. It’s hard to believe that the story of Barbara Hepworth’s studio is so tragic: this sculptor, recognised as one of the most significant British artists of the 20th century, died in a fire here in 1975. Although she never lost her deep connection with her birthplace, Wakefield in Yorkshire, Barbara called St Ives: “my spiritual home”. Her garden in St. Ives remains as a fitting memorial to a worker-artist, a craftswoman whose vision was in her hands.

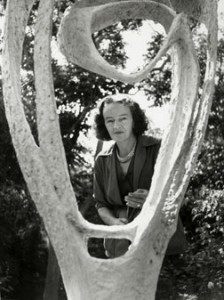

Barbara Hepworth with the plaster of ‘Garden Sculpture’ (Model for Meridian), BH 246, 1958, in her St Ives garden, June 1960; sourced from http://barbarahepworth.org.uk/biography/.

Today, I think of my father who died on 1 June 2006. He was 20 years younger than Barbara Hepworth but he also loved gardening and the outdoors . . . and he wasn’t afraid of manual labour.