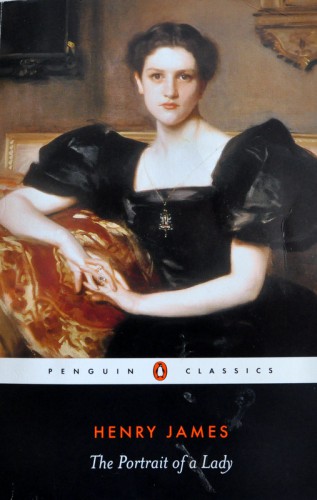

Isabel Archer is a mesmerising character . . . her creator, Henry James, made her so by allowing the reader access to Isabel’s conscious thoughts. A paragraph in ‘The Portrait of a Lady’ (1881) is frequently longer than a page, but how can there be white space on a page if a setting needs visual detail, or if Isabel hasn’t finished a thought process? At least James adhered to a well-formed narrative prose; there’s nothing erratic about his writing. Virginia Woolf preferred a ceaseless, unbroken flow of ideas, feelings, memories that form a fluid stream-of-consciousness. The result is an art form that belies Virginia’s habitual practice of editing and rewriting. Flick through her novel, ‘To the Lighthouse’ (1927), and you’ll be confronted with meandering paragraphs that set out to capture the interiority of the characters; then read the first couple of pages of chapter 42 in Henry James’ ‘The Portrait of a Lady’. For the sake of mere mortals: a paragraph with three to four sentences is considered ideal, followed by a visual rest.

Last week I heard a long-standing academic at The University of Melbourne implore a group of students: “Respect the paragraph”. I detected an internal sigh and perhaps frustration at continually having to read poorly constructed paragraphs. This wonderful teacher also stressed the importance of a well-formed opening sentence that sets up the content of the paragraph. In essay writing this is the topic sentence as it introduces the main theme or idea of the paragraph as a whole. I often look at a paragraph as a mini-essay: the topic sentence is the introduction, the body of the content (or associated detail) comes next, which could be a few sentences, then the final or concluding sentence sums up and provides a link to the next idea in the following paragraph.

The perfect paragraph has a rhythm that carries the reader, best achieved by combining long and short sentences. Too many short sentences, one after the other, can be jarring, and abrupt; too many long sentences can be tiring, and annoying. Of course writers control the pace with their choice of punctuation within sentences … more of that in the next couple of posts.

Coherence and precision are essential elements for a 10/10 paragraph; every sentence and every word should be meaningful. Editing often involves cutting out superfluous words and content, even paragraphs. Each time I rewrite I am determined to make the content tighter— that often means trimming paragraphs. It’s easier for me to edit other writers’ work because I don’t have my ego invested in the writing, and I seem to be able to see superfluous details more clearly! It is often the case that an editor (or the objective eye) who is not familiar with the subject can offer suggestions as to how the first sentence of a paragraph can introduce the idea or theme more clearly.

To finish, a few words from Virginia Woolf (‘Modern Fiction’ essay):

“Let us record the atoms as they fall upon the mind in the order in which they fall … Let us trace the pattern, however disconnected in appearance, which each sight or incident scores upon the consciousness”.

Most of us don’t have that creative luxury in our day-to-day writing, so . . . “Respect the paragraph!”

Next: