Some people feel uncomfortable about abstract art; many would rather dive into a pool of mud than travel an hour by car to see an exhibition featuring art that has been reduced to abstraction with the purpose of conveying ideas and emotion. However, there is nothing muddy about the illuminating abstract art in the current exhibition, ‘Vibrant Matter’, at TarraWarra Museum of Art. This exhibition draws together 56 paintings and sculptures by 35 Australian artists (past and present) who incline towards form, colour and texture as a means of interpreting the world around them. I was invited to the opening last Saturday night, and I can confidently say to both lovers of abstract art and to those who are more skeptical: this exhibition is a wonderful opportunity to experience a diverse cross-section of Australian abstract art that will stimulate discussion about abstraction as an art form.

For me, there are two tests for a good exhibition: quality and coherence. Thanks to the quality of the paintings collected by TWMA, the careful selection of other works to complement the collection, and the praise-worthy curatorial management by Anthony Fitzpatrick, ‘Vibrant Matter’ is an enlightening experience. Words such as ‘metaphysical’, ‘non-figurative’, ‘transformative’, ‘ethereal’ and ‘mimetic’ were bandied around during the opening, but everyone who visits this exhibition should just relax and engage with the works on a personal level; the only requirement is a willingness to reach beyond the confines of one’s mind to be able to connect with art created by another human mind.

Ralph Balson, ‘Constructive painting’, 1953, oil on composition board, 107 x 70 cm, TarraWarra Museum of Art collection. Image reproduced courtesy of Ralph Balson Estate

The first room in the exhibition—which acts like an ante-room before one enters the cavernous central gallery—contains an eclectic array of artworks by a diverse group of Australian abstract artists whose works somehow connect. The first painting I see is by Ralph Balson (1890-1964), Constructive painting (1953), the ‘oldest’ work in the exhibition by an artist who was arguably Australia’s first purely abstract painter. Originally a house painter, Sydney-based Balson first exhibited in 1932. The harmonious composition of Constructive painting incorporates colourful overlapping geometric forms within a cubist space; a perfect example of non-objective art that directly engages the senses. Later in his career, Balson developed a more painterly style (seen in his 1958 Non objective painting on display) which reflected his interest in energy fields of movement and the philosophy of Theosophy that speculates about the nature of the soul based on mystical insight into the nature of God.

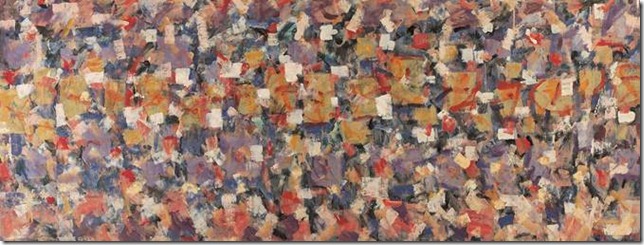

On the adjacent wall to Balson’s Constructive painting is a painting by Melbourne artist, Roger Kemp (1908-1987), Movement in colour (c.1975-76). Kemp was captivated by the dynamic and mysterious forces of our universe and from the 1960s onwards developed his transcendental abstraction that expressed a spiritual universality through his painterly style; he also connected abstract art with Theosophy. In the main, Kemp expressed his love of music through his art: “My inspiration comes from the unseen activity behind all . . . including music”. Wassily Kandinski (1866-1944), credited as the first known abstract painter in Europe, professed that: “Generally speaking, colour directly influences the soul”, equating colour and music with abstract art. As early as 1846, art critic and poet, Charles Baudelaire, explained how colour could enhance the ‘harmony’ and the ‘melody’ of a picture: “The best way of ascertaining whether a picture is melodious is to see it from a distance, so that you cannot grasp the subject nor see the lines”. Viewing Kemp’s Movement in colour from a distance certainly gave me the impression of a rhythmically moving body of tonal colour denoting different melodies. The performance quality is reminiscent of Jackson Pollock’s gestural abstract expressionism.

Roger Kemp, ‘Movement in colour’, c.1975-76, acrylic on canvas, 129.2 x 344.5 cm, TarraWarra Museum of Art collection

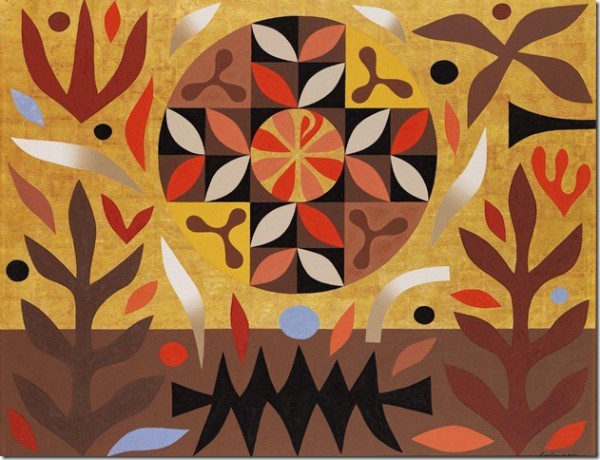

You will discover when reading Anthony Fitzpatrick’s catalogue essay that other artists (such as Yvonne Audette, Godfrey Miller, Robert Owen) in this first room are connected in some way, whether through music, sound, a belief in Theosophy or in Eastern and Western cosmologies, or in the application of the principles of science and mathematics in abstract art. It may be that one artist taught or influenced another. Fitzpatrick tells me that one of his aims when curating this exhibition was for viewers to engage with abstract art on a personal level without inflicting controlled viewing by way of a chronological display or didactic labels. Instead, he has organised the hang in interesting ways—sometimes thematically and, as I noticed when the crowd had dispelled, sometimes tonally, even sometimes according to shapes. For example, the predominantly pink organic lines of Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s Kame Colour IV (1995) blends perfectly with Ildiko Kovacs’ painting, Bloody Mary (2012), hanging next to it; the themes, bold shapes and strong gold and brown tones in Leonard French’s two large 1961 paintings (The Tower and The Creation) harmonise with the featured painting of this review, John Coburn’s Death and Transfiguration (1979).

And so to John Coburn (1925-2006) who often pointed out that the purpose of his abstract art was not to make people see but to make them feel—he described his style as “precise, clear and deliberate” based on simple shapes, flat signs and silhouettes against glowing fields of radiant colour. This fluent and decorative style with spiritual resonances (Coburn was a religious man , born an Anglican and converted to Catholicism) is clearly reflected in his 1979 painting, Death & Transfiguration (featured image; oil and gold leaf on canvas, 150 x 190 cm. Private collection. Image reproduced courtesy of the Estate of John Coburn), which evokes traditional Christian iconography alongside abstracted shapes suggestive of the natural world. Coburn was unfazed by occasional criticisms that his abstract art was repetitive or “merely” decorative.

The Utopia region of the Northern Territory (270kms north-east of Alice Springs) was home for Indigenous artist, Emily Kame Kngwarray (1910-96), her art deeply rooted in the land of her ancestors. Emily painted Kame Colour IV in 1995, a year before she died at the age of 85, and this painting ‘speaks’ of her affinity with her birthplace, Alhalker, an important yam site: “My name is Kam [meaning yam seed or yam flower]and is from that food. When you dig the yam the cracks from the seeds are there”. The colourful and tangled organic lines of this painting bring to mind the many ‘Yam Dreamings’ that Emily painted in this monumental and abstract way to signify the underground network of branching tubers of the yams, and the cracks in the ground that form when the pencil yam ripens. Drawn in continuous lines, the composition has an abstract gestural freedom that resonates with the artist’s intuitive sense of pattern. Emily would have sat cross-legged on the ground, the canvas before her and, starting at the edges, apply the paint, passing the brush from one hand to the other. Which way is up? It doesn’t matter; the rhythmical design can be likened to the veins, cracks and contours of the land seen from an aerial view.

Inge King, ‘Dance around the moon’, 2011, stainless steel, 80 x 94 x 65 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Australian Galleries, Melbourne and Sydney

Whereas Emily Kame Kngwarray’s abstract paintings evoke her spiritual connection with her ancestral land, the luminous stainless steel sculpture, Dance around the moon (2011), by one of Australia’s treasured artists, Inge King, is inspired by her interest in outer space and cosmic forces. Inge was born in Berlin in 1918 and arrived in Melbourne in 1951 at a time when modern sculpture was unheard of; today, her monumental abstract sculptures grace many public buildings, places and plazas. In 1953, along with sculptors Julius Kane, Clifford Last and Norma Redpath (there is a Redpath sculpture in this exhibition: Maquette for a screen 1968), Inge founded the ‘Group of Four’ and in 1961 she was a foundation member of the ‘Centre Five Group’ which fostered “greater public awareness of contemporary sculpture in Australia” by the promotion of abstract sculpture using industrial materials and geometric shapes. Dance around the moon is not on a grand scale but it is breathtaking in its ability to reflect light and, in turn, evoke rotational movement. I first saw this sculpture at the end of Vista Walk, a narrow corridor space that runs along the western wall of the gallery—a set of windows invites visitors to gaze at the rural landscape towards the horizon. As the autumnal sun gradually disappeared, a golden glow filtered into Vista Walk before darkness descended and the gallery lights beamed across King’s sculpture. The surfaces of the two angled rings and the solid central disc shimmered as the scoring created by grinding caught the light; so much so that one can imagine this perfectly balanced artwork reflecting light from the stars and the moon, if it could spin through space.

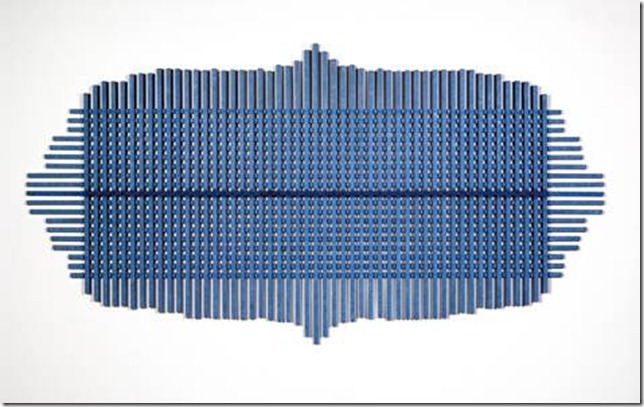

Hilarie Mais, ‘Bay’, 2001, painted wood, 127.2 x 244.8 cm, TarraWarra Museum of Art collection. © The artist, Hilarie Mais

The end room beyond the central gallery provides an opportunity to ‘experience’ the grid in abstract art—artists such as Rosalie Gascoigne, Robert Hunter and Hilarie Mais have created optical effects in their grid-like art through what Fitzpatrick describes as “the potential of the grid to generate highly personal and experiential evocations of natural phenomena in ways which transcend the more rigid, impersonal qualities associated with geometry.” In Mais’ Bay (2001), the grid, with its irregular outline, conveys the curve of a coastline; the blue colour evokes the sea or sky, and the distance between the work and the wall allows shadows to shift across the wall as the viewer walks past—a flickering optical effect transforms this otherwise static grid into vibrant matter.

In the end, the way we see and experience art, whether we’re looking at a Cattapan painting dripping with vivid colour or Michelangelo’s ‘David’, is profoundly personal. What is certain is that our relationship with art is far more than visual; it is social, cultural, emotional, philosophical and spiritual. In every exhibition there will probably be a work that you won’t be able to push out of your mind; it’s not you who takes in the art, but the art that takes over you. For me, abstract art has the ability to reshape the world around us imaginatively, inviting us to inhabit an alternative world and gain another insight into the experience of life itself. It’s all about having an open mind and seeing beyond the visual.

My thanks to Victoria Lynn and the organisers for inviting me to the opening night of this splendid TarraWarra Museum of Art exhibition, and for providing me with material and images for this article. ‘Vibrant Matter’ is a wonderful opportunity for Australians and overseas visitors to gain valuable insight into Australian abstract art within such a delightful setting.

Vibrant Matter

Until 16 June 2013

TarraWarra Museum of Art is about an hour’s drive east of Melbourne.

Opening hours: Tuesday to Sunday 11am – 5pm

Denise, It was lovely to meet you here the other night for the launch of ‘Vibrant Matter’, I hope you enjoyed the evening. Thank you so much for your considered and generous review of the exhibition. It was great to read your thoughts on the show and particularly your response to the selection of works in the article, which were beautifully articulated.

(Anthony Fitzpatrick, curator, TarraWarra Museum of Art) April 2013

My God Denise, you can write about art! Such brilliance – your style shimmers with it. Love the detailed descriptions of the works, and the perceptive curatorial comments. Move over Christopher Allen!