Paris during October 2012 was grey most of the time; the train to Avignon, Provence, delivered us from rain into blue skies, sun and heat. In February 1888 Dutch painter, Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), also travelled to the south of France in search of light and “the future of new Art”. He voluntarily entered the asylum, Saint-Paul de Mausole on the outskirts of Saint-Rémy, in May 1889. Vincent remained there until 16 May 1890 when he moved to Auvers-sur-Oise to be closer to his brother, Theo, who lived in Paris. On 27 July 1890 Vincent shot himself in the chest in a wheat field and died two days later.

Following Van Gogh’s quarrelsome time in Arles with fellow artist Paul Gauguin, and the infamous incident of cutting off his own ear lobe, Saint-Paul was a safe refuge from a world that constantly disappointed him; here he continued to struggle with inner demons yet he pursued his art with as much vigour as he could muster. I visited this old monastery (which has been called a lunatic asylum and a madhouse) just before closing on a mild autumnal day. An eerie peace pervades the ancient cloisters and tiny rooms (or cells) of this place; a place in which a multitude of troubled souls have bravely confronted (and continue to confront) mental illness. Sitting under one of the Romanesque arches that surround the inner garden I contemplated the expressive colour of Vincent van Gogh’s art in the last couple of years of his short, tormented life.

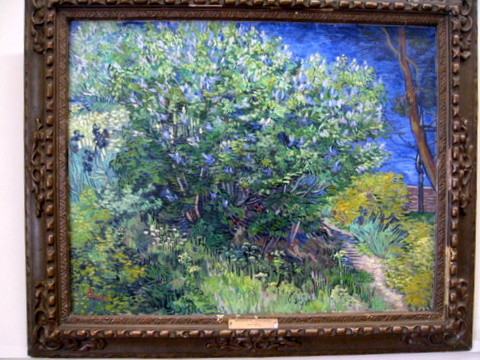

Van Gogh’s bedroom was on the first floor and it is just how he left it, nearly 124 years ago; a small window has a view over the domestic garden and, beyond the walls, gnarled olive trees and erect cypresses emerge; I imagine wild red poppies, lavender, and vivid blue irises under the yellow summer sun. Wandering through the large walled garden to the east of the monastery, we stop at intervals to view prints of Vincent’s artwork hanging on an ancient stone wall (painted during his time at Saint-Paul)—images of swirling skies, twisted trees, wavy grasses, static bushes, butterflies, workers in the fields, stars in an inky night sky, the distant grey horizon of Les Alpilles hills—all showing the distinctive brushstrokes of the artist’s hand seeking perfection, salvation and ultimately, truth to nature. Through Van Gogh’s eyes we see a turbulent heaven and earth; a field of colour and energy. He wrote detailed visual descriptions of what he saw in his many letters; the following is a letter written by Vincent to his friend and fellow artist, Emile Bernard (1868-1941), on 20 November, 1889:

Here’s a description of a canvas I have in front of me at the moment. A view of the garden at the asylum I’m staying in: on the right, a grey terrace, a wall of the building. A few denuded rose bushes; on the left, the ochre-red of the garden soil, the ground scorched by the sun, covered in fallen pine and needles. The edge of the garden is planted with tall pine trees with ochre-red trunks and branches and green foliage made dark by mixing black. These tall trees stand out against an evening sky streaked with violet on a yellow background, the yellow turning pink higher up, and to green. A wall—again painted ochre-red—closes off the view with only a violet and ochre-yellow hill rising above it … Under the trees, vacant stone benches, gloomy box, the sky reflected—yellow—in a puddle after the rain. A ray of sunlight, the last glimmer of day, lifts the sombre ochre almost to orange. Small black figures wander about among the tree trunks.

Such a lucid visual analysis of a view from a small window! Van Gogh didn’t need a camera—his informal study of Japanese ukiyo-e woodblockprints encouraged him to shed the burden of photographic realism and move towards a more decorative, stylistic representation of subject matter. He copied the Japanese technique of using colour and suppressing shadow to intensify emotional effect, regarding this as important in eliminating impressionist naturalism. Vincent wrote to Theo on 5 June 1888 (Arles): “. . . you view things with a more Japanese eye, and you get a different feel of colour”. Applying thick paint with jabbing brushstrokes added intensity to Van Gogh’s colours, an important component of his expressive style, intensified by his state of mind. In many ways Vincent was one of the first Expressionists, paving the way for Modernists such as Henri Matisse and Edvard Munch.

Emphasis was made of man’s relationship with nature by the Romantic painters and poets such as William Wordsworth, Caspar David Friedrich and John Constable. J.M.W. Turner painted sublime scenes of storms, mountains, steam-spewing trains carving up the countryside; Constable painted local landscapes of working people in sync with nature. Towards the end of the 19th century there was a move by artists to modify the urge to paint awe-inspiring, panoramic landscapes and explore inner responses to nature. Artists moved out of the studio to paint directly before nature. Whenever Van Gogh was well enough he set up an easel in the garden of Saint-Paul or went under supervision into the surrounding fields. It’s amazing that anyone can see so much colour and life in a tough Provencal bush . . . but Vincent did . . . nature absorbed him.

Van Gogh’s episodes of epilepsy, manic depression and hallucinations at Saint-Paul were frequent, but in between these periods he painted and painted, forging a new vision of artistic representation and expression. I visited Saint-Paul on 14 October 2012 and stood in the room where Vincent van Gogh slept for a year; a room facing east with a view of nature towards the rolling hills of Les Alpilles . . . a place where art and illness interacted with triumphant results.