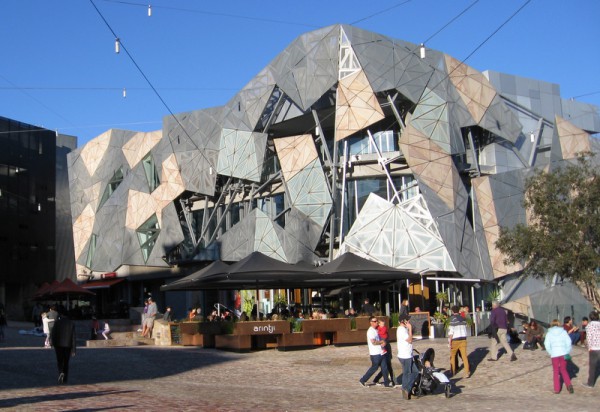

Melburnian notable, Barry Humphries, always gives his honest opinion—often through the sharp tongue of his alter ego, Dame Edna Everage. He was less than flattering when he described the bold geometric façade of Melbourne’s Federation Square (built to commemorate Australia’s centenary in 2001) as “getting used to leprosy”. Others consider Fed Square to be a dynamic meeting place on the banks of the Yarra River, enlivened by contemporary architecture and design.

On June 8th 1835, John Batman ‘purchased’ land from the local Australian Aborigines (the Wurundjeri clan) with the intention of building a village in the new British colony of Victoria. He wrote: “The boat went up the large river I have spoken of … and I am glad to state about six miles up … This will be the place for a village.” No, no, Mr Batman! I think you meant ‘the site for a village’. A site (on a map) will become a ‘place’ once it accumulates an aesthetic dimension through cultural building blocks, social interaction and art (such as architecture, street art, public gardens) contained within its visual ‘boundaries’. The “large river” Batman described was eventually called the Yarra River and in 1837 the “village” was named Melbourne.

Of course in 1835 this site on the banks of the Yarra River at the head of Port Phillip Bay was already an established place of deep spiritual, physical and psychological meaning for the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation. They called the river ‘Birrarung’ (place of mists and shadows). Aboriginals have a firm attachment to the place where their ancestral spirits dwell. Associated ancestral narratives or ‘Dreamings’, and particular clan-based imagery, are manifested in the artistry of key artists. Art historian, Paul Carter, calls this conception of ‘place’ as placedness in which geography, history, political and social organisation are woven into a singular metaphysics of individual and collective identity. The art of these places (or sacred sites) is traditionally in the form of body painting, sand art, rock and bark paintings using crushed rock (ochre). Contemporary Aboriginal artists still paint their Dreaming narratives (Tjukurrpa) and their ancestral places, but mainly with brightly coloured acrylic paints on canvas.

So when we think of ‘place’ we don’t have to think of inert bricks-and-mortar. A garden is ‘built’ and shaped out of a wilderness into a place of art. Andre Le Notre’s baroque masterpiece at Versailles is a supreme example, Vita Sackville-West’s colour coordinated garden rooms at Sissinghurst are enchanting, and my backyard greenery may not be a work of art but it is a place of beauty and special meaning for me. Someone who regularly walks down a well-worn beach track which opens to an expanse of sea in all its moods, with gnarled trees bending to frame the view, may consider this vista as a place of art.

A church built in a city urban space will transform that space into a place of communal importance, and the interior of the church will become a place of worship and art. Ancient Greek temples and theatres such as the Delphi theatre (pictured left) were built for the same reason and integrated into an urban context using the terrain to assist in the creation of the structure. The result is striking, primarily due to the dramatic positions of the theatres, usually on hillsides. The Delphi theatre looks down on the temple and the valley beyond, a perfect example of performance and audience interacting with nature and a sacred landscape. This is a place of beauty and great spiritual significance to the people—a fusion of human and natural order.

Walk into a cavernous Counter-Reformation church in Rome such as Il Gesu and you won’t need to be Catholic to be completely overwhelmed by the interior and mesmerised by the art. Can you imagine being present during a liturgical service in the 17th century with the combined visual and auditory power of baroque art and music? Parishioners would lift their eyes to the illusionistic trompe l’oeil painted ceiling (pictured below) with its view of heaven. The art of this place is an engine of religious devotion which has inspired, and will continue to inspire, not only a devout Catholic congregation but also strident non-believers.

Note-worthy eye witness writers such as Charles Dickens, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, William Wordsworth and Mary Wollstonecraft have given us wonderful travel letters, poetry and journals which effectively transport us to the places they have visited. American writer, Henry James (1843-1916), attended a service in Il Gesu on New Year’s Eve, 1873, and he related his impressions and observations in his travelogue, Italian Hours:

The church is gorgeous … There is a vast dome, filled with a florid concave fresco of tumbling foreshortened angels, and all over the ceilings and cornices a wonderful outlay of dusky gildings and mouldings. There are various Bernini saints and seraphs in stucco-sculpture … The high altar a great screen of twinkling chandeliers … Near me sat a handsome, opulent-looking nun … Can a holy woman of such a complexion listen to a fine operatic baritone in a sumptuous temple and receive none but ascetic impressions? What a cross-fire of influences does Catholicism provide!

Giovanni Battista Gaulli, ‘The Triumph of the Name of Jesus’, fresco ceiling, 1672-85, Church of Il Gesu, Rome

If you think about the art of ‘place’ and the place of art in a local, national and global context, there has been a gradual transition from temple and church, to gallery, to gardens and to the streets of everyday life. So in recent years it’s not only the place but also the authority of art that has been transformed. Walk down Hosier Lane in Melbourne and consider the graffiti which has made this place so lively. Many would consider this street art as unsanctioned expressions of the artist which defaces the architecture. What do you think?

I’ve only scratched the surface of what it means when we talk about ‘place’ and its associated art – public, private, spiritual, sacred, man-made, wild, tamed, sweeping vistas … and so on. Art in public places can be controversial, yet it engages with humans and brings people together from all walks of life and from all over the world. How exciting! A place is infused with symbolic meaning and there is often a sense of universal belonging and shared identities—or just a personal attachment.