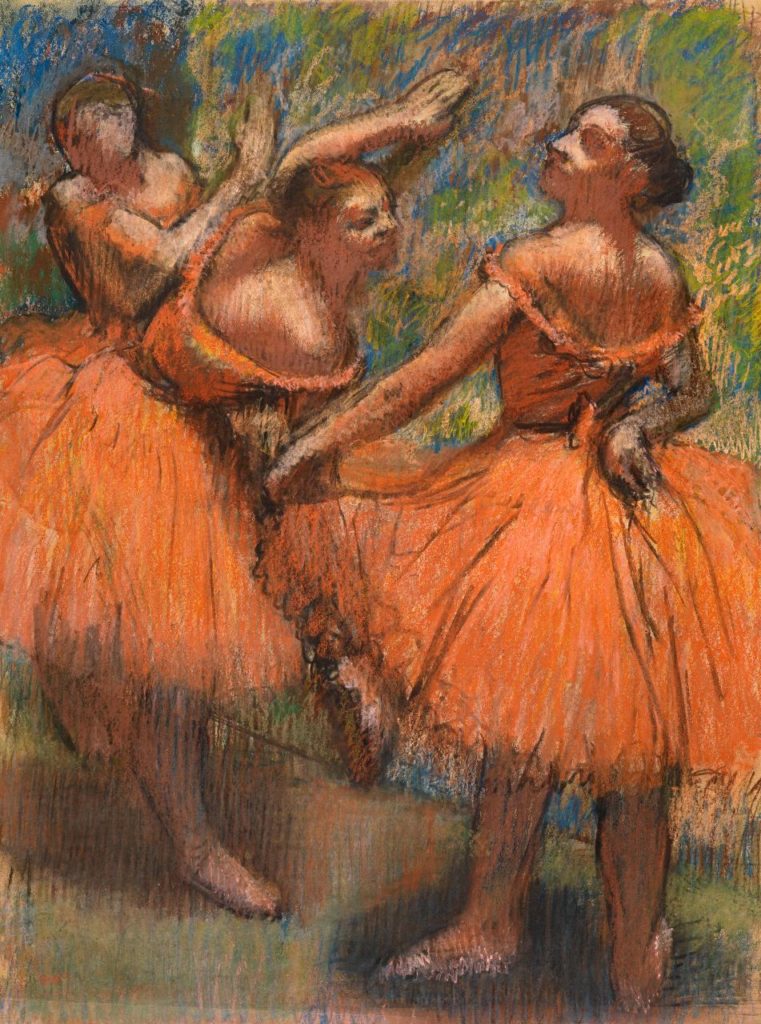

If you think Edgar Degas (1834-1917) just painted pretty ballerinas in soft pastels, then you’ll know otherwise once you’ve visited the National Gallery of Victoria exhibition featuring works spanning more than five decades of the French artist’s career. You’ll find out that this enigmatic man depicted modern Parisian life—warts and all—in many intriguing ways. Some pigeon-hole Degas as an Impressionist, but although he exhibited with artists associated with the Impressionist movement, such as Manet, Monet, Morisset, Cezanne and Pissarro, he refused to be called an Impressionist. Degas believed that an artist’s imagination should be “freed of the tyranny of nature . . . the air that we see in a painting by a master is never air that can be breathed”. He worked on dozens of preparatory drawings and painted sketches in his studio before completing a finished work—a far cry from any concept of an ‘impression’.

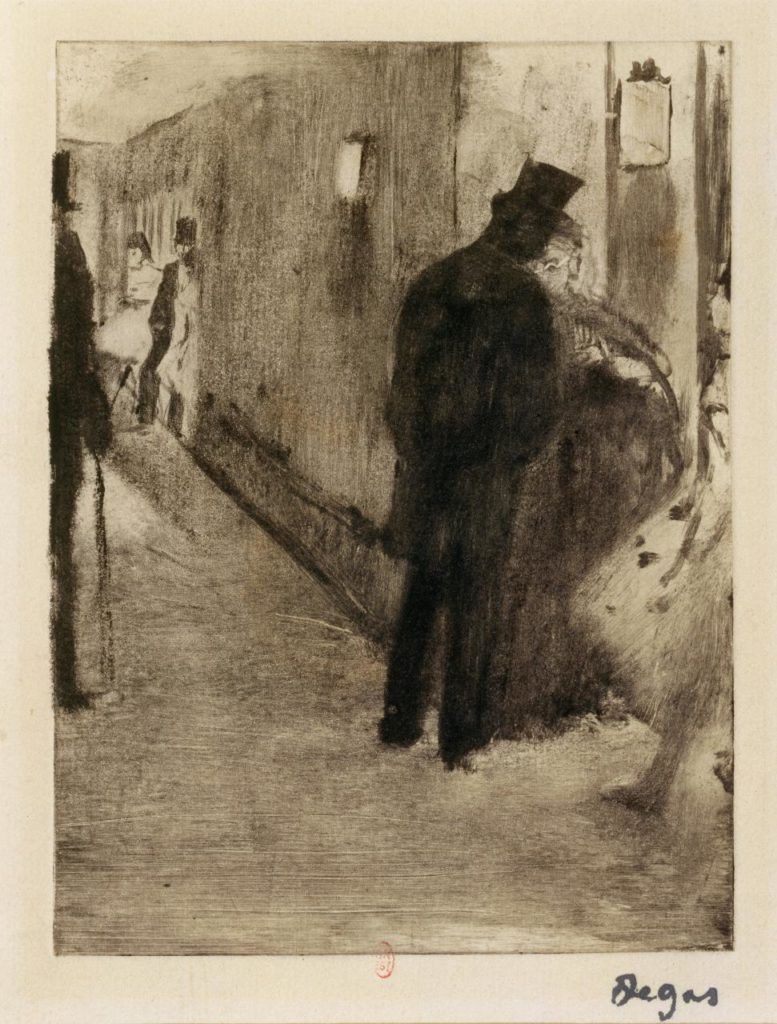

Why is this exhibition ‘a new vision’ of Degas? Well, because Henri Loyrette, former director of the Louvre and of the Musee d’Orsay, and a world authority on Degas, assures us that there is always something new to discover about Degas and his art. Luckily, the NGV has contracted Loyrette to curate this panoramic survey of the artist, which includes an array of his paintings, sculpture, drawings, prints and photographs.

Edgar Degas, ‘Nude woman standing, drying herself’, 1891–92, lithograph, fourth of six states, 33.1 x 24.8 cm (stone), 44.8 x 36.2 cm (sheet), Sterling and Francine Clark Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts.

On entering the first gallery space, which isn’t large, a self-portrait of Degas (1857) is displayed alongside outlines of female bodies in various poses; a central display case exhibits a sculpture of a female nude’s curvaceous contours (Woman taken unawares, c. 1892, cast 1919-32, bronze). Degas regarded his sculptures as stages in the progress of his research into the nature of movement and musculature. This room introduces the visitor to the artist and his life-long obsession with “the silent eloquence of limbs in motion”.

The influence on Degas of the Flemish and Italian masters, whose work he studied and copied in the Louvre, and also his admiration for the Neo-Classical and Realist French painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), is well documented and can be identified in the room to the right. The Roman beggar woman (below), which Degas painted in 1857 during his study tour of Italy, is a fine example of these influences and what took his fancy as subject matter in his early career. He was only 23 years old but he has mastered a mature psychological portrait of this Italian woman. The brown tones effectively evoke poverty and aging. One of Degas’ enduring aims was to be a classical painter of modern life: “My art has nothing spontaneous about it, it is all reflection”.

Edgar Degas, ‘Roman beggar woman’, 1857, oil on canvas, 100.3 x 75.2 cm, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery.

The young, eager painter took Ingres’ advice to focus on drawing lines, not directly from nature, but “always from memory”. This principle stayed with Degas throughout his career, even though it was at odds with the Impressionists, who painted en plein air, capturing the effects of light and atmospheric conditions. There are a handful of interesting landscapes in this show; but as Degas matured, he preferred to depict the sweatshops and reality of everyday living in Paris featuring lower-class working women.

Born into the wealthy Franco-Italian-Creole De Gas family in 1834, first-son Hilaire-Germain-Edgar (his surname was later condensed to Degas) left Paris 22 years later, thanks to his father’s wealth, and travelled to Naples to visit his paternal grandfather, Hilaire, who had fled the French Revolution. Degas studied at the Villa Medici in Rome before moving to Florence late in 1858 where he stayed with his father’s sister Laure Bellelli and her family. Degas painted a ‘dark’, psychological portrait of this family between 1858 and 1867, which can be viewed in the next exhibition space. It is well-documented that Laure and Edgar were fond of each other. Degas was aware of her unhappy marriage to Gennaro, and he conveys this marital discord in Family portrait, also called The Bellelli family, painted in an enlarged history-painting format.

Edgar Degas, ‘Family portrait , also called The Bellelli family’, 1867, oil on canvas, 201.0 x 249.5 cm, © Musée d’Orsay.

Laure looks into the distance while Gennaro Bellelli is seated with his back to the viewer. The unconventional composition combines classical serenity with psychological tension, giving the work an unsettling atmosphere. Placement of the figures is suggestive of the parents’ alienation from one another, and perhaps of the divided loyalties of their children. Laure stands, as if for an official portrait, her expression indicative of her unhappiness, one hand resting protectively on Giovanna’s shoulder as the elder sister looks at the viewer. Giulia sits on one leg facing her father with her hands on her hips as if in defiance. Hilaire Degas, who had just died, is seen in the drawing on the wall. The family dog, glimpsed at the lower right corner, is sensibly sneaking out of the picture. Laure’s note to Degas after he had returned to Paris is revealing: “You must be very happy to be with your family again, instead of being in the presence of a sad face like mine and a disagreeable one like my husband’s”.

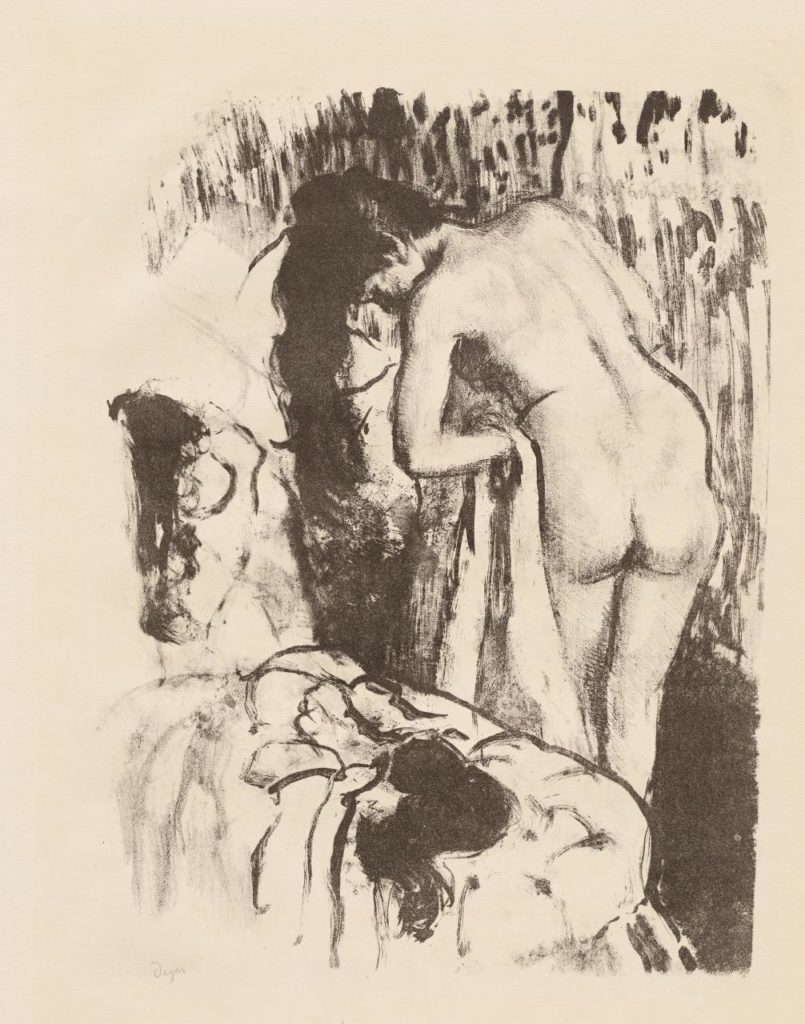

Edgar Degas, ‘Edmondo and Thérèse Morbilli’, c. 1865, oil on canvas, 116.5 x 88.3 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

In 1863 Degas’ sister Thérèse married their first cousin Edmondo Morbilli, who lived in Naples. This portrait of the married couple was probably painted in 1865 during the couple’s visit to Paris following the tragic loss of a child, expected in early 1864. Thérèse sits, literally and figuratively, in the shadow of her husband, and Degas contrasted her anxious expression with Edmondo’s aloof look of self-assurance. The subdued greys and blacks of their clothing are set off against the drapery behind them and contrast with the richly embroidered Islamic textile on the table. This painting recalls portraits from the Italian Renaissance. The fact that Degas never married, or had a lasting relationship with a woman, is often attributed to the loss of his mother at the age of 13, and the unhappy marriages of his beloved sister and aunt.

In January 1862, while copying a Velázquez at the Louvre, Degas met the artist Edouard Manet, two years older than him, and he introduced Degas to the circle of Impressionist painters. It was in part due to Manet’s influence that Degas turned to subjects from contemporary Parisian life, including café scenes, the theatre and dance. There are two portraits of Manet (one black chalk and the other an etching) by Degas in the show.

The exhibition design is thoughtful and directs visitors through this substantial survey of Degas’ art. Walking past the Manet portraits, I spied a bronze statue of a young ballerina through a slit in the wall—an ingenious intervention. I turned the corner and there were his painted ballet dancers of the 1870s, marking Degas’ move from Realist portraits towards a looser, more painterly style evoking his lifelong enchantment with ballerinas and the theatre. Degas’ ballet pictures—dancers at the barre in the rehearsal studio, sometimes under the watchful gaze of the ballet master—are among the defining images of Degas’ art.

Edgar Degas, ‘The little fourteen-year-old dancer’, 1879–81, cast 1922–37, bronze with cotton skirt and satin ribbon, 99.0 x 35.2 x 24.5 cm, Museu de Arte de São Paulo, Assis Chateaubriand.

One of the stars of this show is The Little Fourteen-year-old Dancer, a statue of a bronze girl about two-thirds life-size with her hands locked behind her back, dressed in a tutu, and real hair tied with a ribbon. The flesh-toned waxen ballerina (cast in bronze in 1922 after Degas’ death) was modelled on Belgian dancer, Marie Van Goethem, and caused a sensation at the sixth Impressionist exhibition in 1881. Reviewers suggested that it should be placed in a museum of zoology or anthropology; it was seen as an ethnological specimen, rather than a work of art.

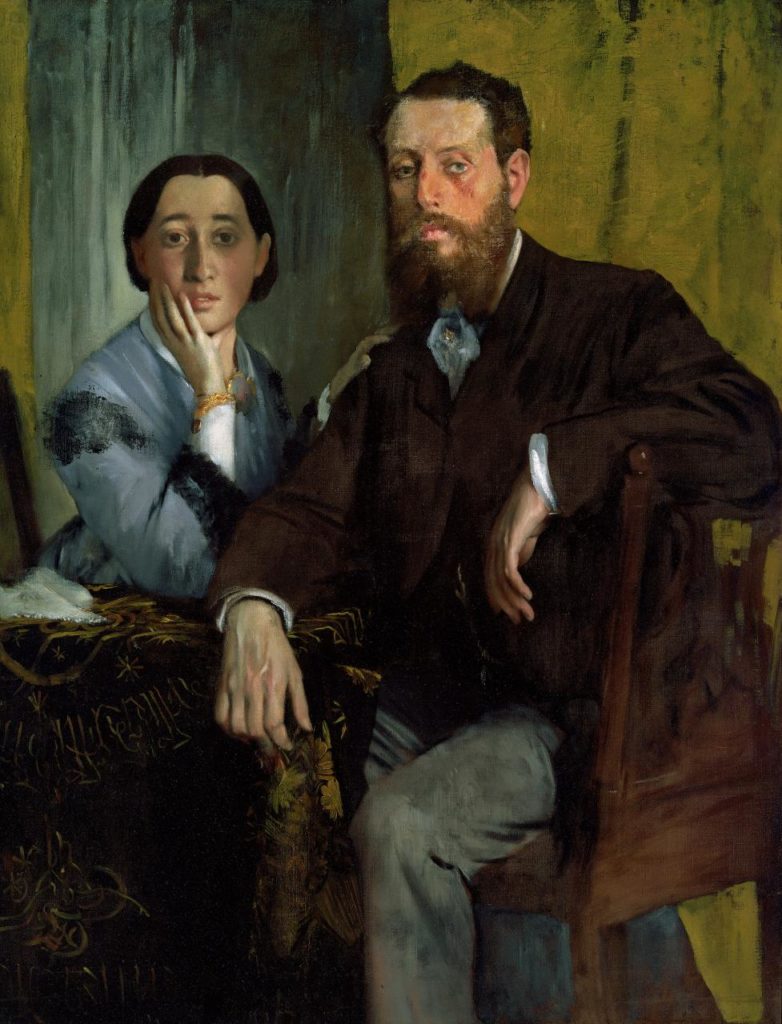

Edgar Degas, ‘Ludovic Halévy talking to Madame Cardinal’, 1880–83, monotype, 15.8 x 11.8 cm (plate), Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Degas loved to experiment, and this is most apparent in his monotypes. Inky shapes and shadowy atmospheres materialise from murky blackness due to his technique of drawing in ink directly onto a metal plate using incising tools, rags, and his fingers. Then he would lay a sheet of damp paper on the plate and run it through a press. His monotypes allowed him to renew himself by partially abandoning the classicism he had first practiced. These works, particularly those created between 1876 and 1885, are suited to the subject matter depicting the seedy underbelly of Paris in the mid- to late-nineteenth century: crude brothel scenes and images of men dressed in black with top hats lurking around the wings and dressing rooms of the theatre seeking sexual favours. They were wealthy male subscription holders, called abonnés, who preyed on young, low-paid ballet dancers. Degas sought the help of these influential friends to slip him into the ballerinas’ private world.

Edgar Degas, ‘In a café (The Absinthe drinker)’, c. 1875–76, oil on canvas, 92.0 x 68.5 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

As the exhibition advances there are more contemporary images of the realities of modern living behind closed doors in Paris: laundresses labouring, women bathing, dancers . . . and a striking oil painting of a man and a woman sitting side-by-side in a Parisian café, locked in silent isolation with eyes empty with rounded shoulders. The Absinthe drinker illuminates the dangers of consuming the liquor called absinthe. Although this looks like a snapshot taken by an onlooker at a nearby table, this is deceptive because, in fact, the real life effect is manipulated by Degas in his studio and not in the café. Degas enlisted friends to pose for him: Ellen André, an actress, and Marcellin Desboutin, an engraver and artist, who liked to dress up as a tramp.

Edgar Degas, Woman at her toilette, c. 1894, charcoal and pastel on paper, 95.6 x 109.9 cm, Tate, London.

The physicality of Degas’ oils, charcoals and pastels seemed to burst across the composition with vibrant colour from the 1890s. A faceless young woman combs her long hair in the painting, Woman at her toilette, loaned from the Tate Gallery in London. It borders on abstraction, enlivened through his inventive technique and materials. By now it’s quite obvious that Edgar Degas liked to watch women, but the women that we see in his art—women ironing, bathing, towelling off, combing their hair, performing on the stage—seem oblivious to his presence. Nude women are frequently depicted in unflattering poses. For twenty-first-century viewers this may get a little creepy—particularly for female viewers—and as the exhibition unfolds, feelings of this kind may hinder any aesthetic appreciation of Degas’ artistry. The fin de siècle decadent writer J. K. Huysmans wrote that Degas regarded women with “an attentive cruelty, a patient hatred”. Loyrette rejects this claim. Some would conclude that Degas had a lofty indifference to women; others could view his labouring laundresses and intimate scenes of dancers and women bathing as sympathetic. On the other hand, the brothel monotypes depict prostitutes with (cruelly) caricatured faces. Julian Barnes, in his essay on Degas, reminds us that “we all import our prejudices.” (‘Keeping an Eye Open’, p. 122). Degas was a brilliant artist, but also a baffling one.

Walking through a ‘forest’ of sculptures of female bodies I turn the final corner and see a smallish sculpture of a horse displayed in a glass cabinet. On the surrounding walls there are more paintings of racehorses at the starting line, revealing Degas’ lifelong interest in horse musculature, colour and movement. The Degas sculptures displayed throughout this exhibition embody a Rodinesque, hands-on expressionism, but with a unique Degas ‘touch’.

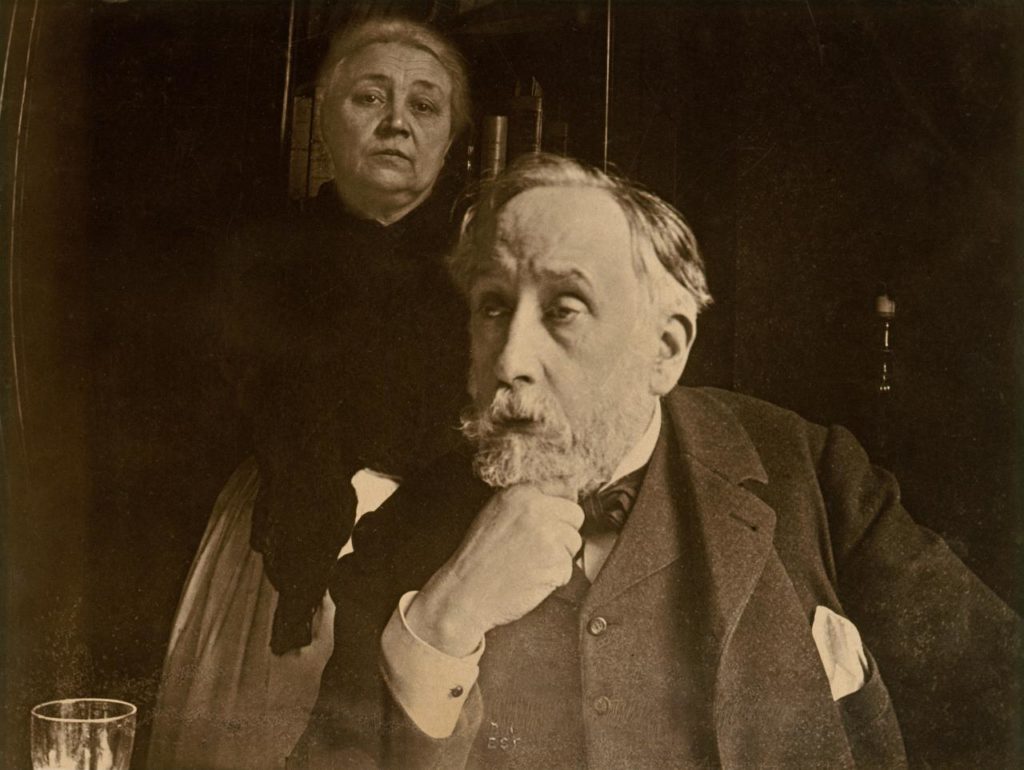

Edgar Degas, ‘Self-portrait with Zoé Closier probably autumn’, 1895, gelatin silver print, 18.2 x 24.2 cm (image and sheet), Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

The second last room displays a small collection of Degas photographs. In 1895, when Degas was in his 60s, he took up photography. If you take a good look at his self-portrait (above), you can imagine a grumpy man ordering about his housekeeper, Zoé Closier. Degas poses with his bearded chin resting on his fist as Zoé stands behind him in the shadows. This is a good place to reflect upon Degas’ long life, and how much he achieved.

Edgar Degas, ‘Dancers on the stage’, c. 1899, oil on canvas 76.0 x 82.0 cm, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon.

In the works of his final years, one is struck by Degas’ obsession with certain poses and angles of long-limbed female dancers. He seemed more interested in groups of weary ballerinas waiting in the wings, stretching, adjusting a strap, massaging sore ankles and feet. Degas made use of every medium at his disposal: charcoal, pastel, oil paint, paper, canvas, board; and he experimented with technique, such as layering and adding pastel to wet paint.

Edgar Degas stopped working in 1912. In hermit-like isolation, he survived until 1917, dying at the age of eighty-three. He had no will, so his works were never housed in their own gallery; instead, they were auctioned off and ended up all over the world. The NGV has loaned many of them for this ‘solid’, cleverly designed and curated exhibition. Degas was a paradoxical man, a solitary soul, and an ingenious artist who pushed the boundaries of conventional art in his drive to convey the reality of life in late-nineteenth-century Paris.

‘Degas: A new Vision’ runs until 18 September.

The excellent exhibition catalogue includes a substantial scholarly essay on Degas by Henri Loyrette.