The famous literary Brontë family lived in Haworth Parsonage, Yorkshire, between 1820 and 1861. Their austere grey-stone home, surrounded by dark-green trees, prickly hedges and bleak moors, is infused with gothic imaginations. Even though it is now the Brontë Parsonage Museum, and nothing can be touched, this is a place where astonishing art was created by three sisters. I imagine Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë telling stories and writing by a glowing peat-fire as the bone-chilling wind whipped around the Parsonage then roared back across the moors. It was here that Charlotte secretly created Jane Eyre, a “poor, obscure, plain, and little” orphan, who becomes a governess and finds her place in a ‘man’s world’. Charlotte published Jane Eyre in a novel of the same name in 1847, but under a pseudonym, Currer Bell, a man’s name. It was an instant success. Tragically, Charlotte died eight years later at the age of 39, Emily and Anne having already succumbed to illnesses before her.

‘Charlotte Brontë’ by George Richmond, 1850, chalk, 600 mm x 476 mm. Bequeathed by the sitter’s husband, Rev A.B. Nicholls, 1906. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Jane Eyre declares, surely on behalf of Charlotte, that “I am no bird; no net ensnares me; I am a free human being with an independent will.” A confession: I’ve never been able to empathise (or even sympathise) with Mr Rochester and his tedious, taunting courtship of Jane—how dare he call her “my good little girl”?

Above all, Jane’s denunciation of female servitude has always struck the right note for me. Women, she says, “need exercise for their faculties . . . they suffer from too rigid a restraint, too absolute a stagnation, precisely as men would suffer; and it is narrow-minded . . . to say they ought to confine themselves to making puddings.”

In 1916, one hundred years after Charlotte Brontë was born, Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary that the reader [of Jane Eyre] should imagine Charlotte living in:

a remote parsonage upon the wild Yorkshire moors. In that parsonage, and on those moors, unhappy and lonely, in her poverty and her exaltation, she remains for ever. These circumstances, as they affected her character, may have left their traces on her work. . . . As we open Jane Eyre once more we cannot stifle the suspicion that we shall find her world of imagination as antiquated, mid-Victorian, and out of date as the parsonage on the moor, a place only to be visited by the curious, only preserved by the pious. So we open Jane Eyre; and in two pages every doubt is swept clean from our minds. The writer has us by the hand, forces us along her road, makes us see what she sees, never leaves us for a moment or allows us to forget her. At the end we are steeped through and through with the genius, the vehemence, the indignation of Charlotte Brontë.

Every time I open Jane Eyre the story transports me to familiar places that never fail to stimulate my senses, and I can always imagine Charlotte being there with Jane, even though Jane Eyre is not Charlotte’s autobiography. There’s the young Jane hiding away in her own no-man’s land, a window seat where she sits “cross-legged, like a Turk”, immersing herself in the pages of Bewick’s History of British Birds. A red curtain conceals Jane from the rest of the room, while the glass protects her from “ceaseless rain sweeping away wildly from a long and lamentable blast”. The weather is not for the faint-hearted in Haworth, and it is used in the Brontë novels with great effect to reflect human states of emotion.

The windswept moors where the Brontë children played were full of wild places free of Victorian convention and their father’s dominance. In her preface to Emily’s poetry, Charlotte describes the harsh moors as a place where “imagination can find rest”:

“The scenery of these hills is not grand – it is not romantic; it is scarcely striking. Long low moors, dark with heath, shut in little valleys, where a stream waters, here and there, a fringe of stunted copse. Mills and scattered cottages chase romance from these valleys; it is only higher up, deep in amongst the ridges of the moors, that Imagination can find rest for the sole of her foot: and even if she finds it there, she must be a solitude-loving raven – no gentle dove. If she demand beauty to inspire her, she must bring it inborn: these moors are too stern to yield any product so delicate.”

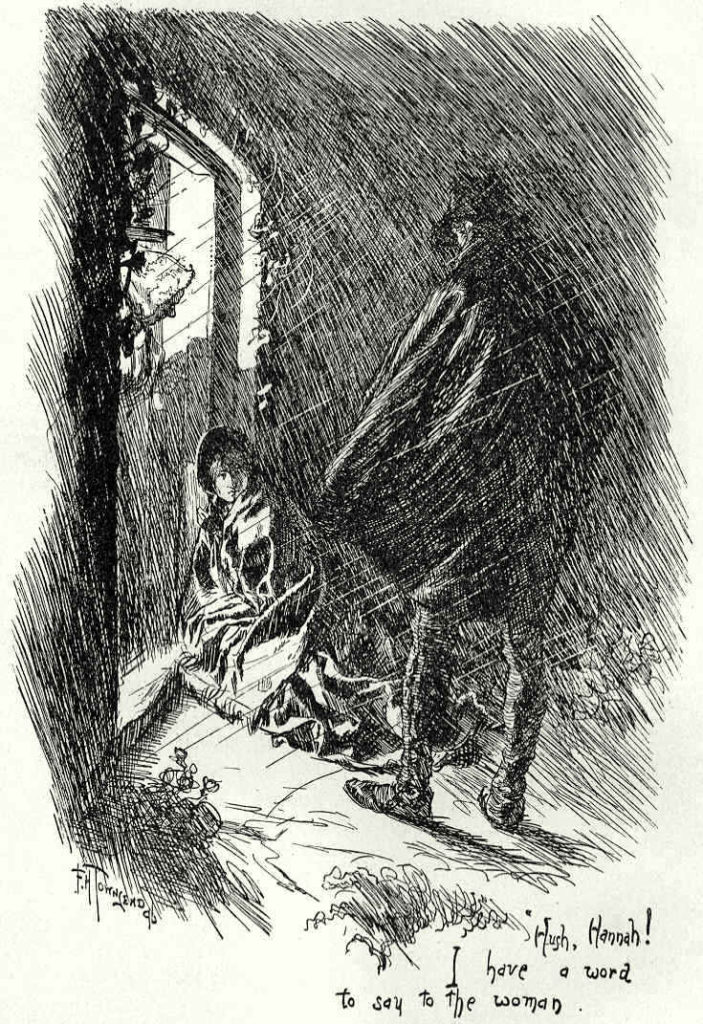

Jane’s solitary and sorrowful journey across the moors is reflected in the words that Charlotte writes, ending when Jane sees “a trace of light” that leads her to Moor House, where shelter and congeniality are embodied in the welcome warmth of a fire:

“The night-wind swept over the hill and over me, and died moaning in the distance: the rain fell fast, wetting me afresh to the skin. I could see clearly a room with a sanded floor, clean scoured; a dresser of walnut, with pewter plates ranged in rows, reflecting the redness and radiance of a glowing peat-fire.”

St John Rivers admits Jane to Moor House. Illustrator: F.H. Townsend, 1897, ‘Jane Eyre: An autobiography’.

Like Virginia Woolf and many other pilgrims, I climbed the steep cobblestone lane to reach the parsonage where Charlotte’s family lived . . . and the modern world just fell away before my eyes (it was delicious). Even though I passed the churchyard on a clear-blue-sky autumn morning, it was darkened with age and overhanging trees. Tall, gothic-looking gravestones lean at different angles, their mossy faces recording lives snatched away by cruel Victorian diseases and malnutrition. Charlotte’s small body was too frail to overcome tuberculosis, or a similar illness, and she died on 31 March 1855. She had been married to her father’s curate, Arthur Bell Nicholls, for a brief nine months. Charlotte’s suffering and loneliness can only be imagined. Revd Patrick Brontë, an Ulster Anglican of humble origins, outlived his wife Maria and all six of his children. Such carnage was hardly unusual in Haworth, where the average life expectancy was about 25 in the mid-nineteenth century.

The Brontë Parsonage remains much as the family would have known it: Patrick Brontë’s study, with its piano and view of the church; the dark kitchen; and the cramped bedrooms with views over the graveyard. But one cannot help being intoxicated with imaginings on entering the dining room. This is where the Brontë sisters shared their ideas while darkness blanketed the moors. And this is where their imagination rested in ghostly silence while stories such as Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre were painstakingly handwritten around a table before a radiant fire.

At the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth this year there are celebrations marking Charlotte Brontë’s 200th birthday (she was two hundred years-old on 21 April) including the exhibition “Charlotte Great and Small” curated by author, Tracy Chevalier. On display are the small things in Charlotte’s life: her shoes and the miniature books that the Brontës famously constructed. There are also quotes voicing Charlotte’s great desires.

Along with her two sisters, Charlotte Brontë has been an inspiration to writers, especially women, ever since she published Jane Eyre. Chevalier’s new book, Reader, I Married Him: Stories Inspired by Jane Eyre, brings together renowned contemporary female authors and their short stories using the well-known line from the novel as a springboard for flights of their own imagination.

Featured photo: www.beautifulenglandphotos.uk/haworth-yorkshire/