The aim of the first sentence of any written work is to motivate the reader to read on; it can be decisive and declare the theme or argument of the main body of writing, or it can be a teaser. So whether you’re writing a novel, an essay, or just an email, your aim is to arrest the reader’s attention immediately, and keep it under your control until the end. Find the right words, the right tone, the right punctuation; then, after you’ve let it ‘sit’ for a while, edit and proofread with care.

Take note of how an experienced newspaper journalist adds punch to sustain interest in the opening paragraph. To illustrate the importance of being masterful when you ‘put pen to paper’ to write the first sentence (or I should say: ‘put fingers to the keyboard’), I’ve chosen three openers by well-respected writers. Here are the first two:

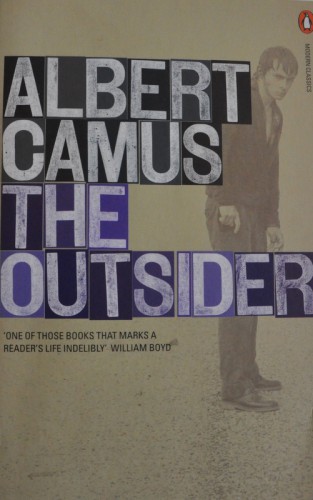

Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday, I don’t know. (Albert Camus, ‘The Outsider’, first published in French, ‘L’Etranger’, 1942)

Time is not a line but a dimension, like the dimensions of space. (Margaret Atwood, ‘Cat’s Eye’,1988)

These opening sentences immediately engage with the reader, and, at the same time, they satisfy the golden rule: start with a subject and activate it with a verb. The subjects here—‘mother’ and ‘time’—are clues that will only be fully understood as the narrative unfolds. Camera, lights, action! Reading the first sentence in ‘Cat’s Eye’ makes us aware that this story is going to be complex and challenging whereas we are instantly affronted by the indifference of the narrator to his mother’s death in the opening line of ‘The Outsider’. Even though Camus ‘says’ so much with so few words (Hemingway is another writer who is sparing with words), my favourite opening sentence was written by Charles Dickens in ‘A Tale of Two Cities’ (1859):

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair . . . (59 words later, the sentence finishes).

Dickens’ breathless opening sentence is punctuated with commas; it pulsates with confusion, contrast and fear—the bloody revolt by French peasants in 1789 during the Age of Enlightenment is foreshadowed, and the British are fearful. The repetition of “it was” vibrates like the beat of a drum or the incessant action of the guillotine. This gripping opener is a work of art by a master craftsman; tension is established and curiosity aroused. An editor wouldn’t touch it.

Today, it’s rare to find an opening sentence with more than 100 words in any writing genre—rather, ‘short and to the point’ is favoured; maybe with an element of shock to grab the attention of the frequently distracted modern reader.

Next topic: