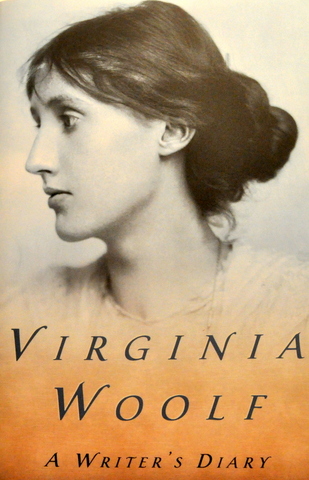

The habitual practice of writing in a notebook, a diary or a journal will refine your writing. A journal can include jottings of daily observations, lists of words and punctuation that interest or bother you, inspirational sentences you’ve read, ideas to develop, critical editing of current writing, and so on. Literary icon, Virginia Woolf, born in 1882, began writing a diary in 1915 and continued to do so until four days before her death in 1941, leaving behind 26 volumes. More than a tool of self-exploration and critical observation, Virginia approached her diary as a means of refining her craft so that each writing project became, in time, a work of art. After Virginia’s death, her beloved husband, Leonard Woolf, extracted selected diary entries and published a compilation in ‘A Writer’s Diary’ (first published in 1953). He commented in the Preface that “she is obviously using the diary as a method of practising or trying out the art of writing.” Her diary writing is a constant joy and motivation for me. Virginia wrote on Easter Sunday, 20 April 1919:

“. . . I got out this diary and read, as one always does read one’s own writing, with a kind of guilty intensity. I confess that the rough and random style of it, often so ungrammatical, and crying for a word altered, afflicted me somewhat. I am trying to tell whichever self it is that reads this hereafter that I can write very much better; and take no time over this; and forbid her to let the eye of man behold it. And now I may add my little compliment to the effect that it has a slapdash and vigour and sometimes hits an unexpected bull’s eye. But what is more to the point is my belief that the habit of writing thus for my own eye only is good practice. It loosens the ligaments. Never mind the misses and the stumbles. Going at such a pace as I do I must make the most direct and instant shots at my object, and thus have to lay hands on words, choose them and shoot them with no more pause than is needed to put my pen in the ink. I believe that during the past year I can trace some increase of ease in my professional writing which I attribute to my casual half hours after tea. Moreover there looms ahead of me the shadow of some kind of form which a diary might attain to. I might in the course of time learn what it is that one can make of this loose, drifting material of life; finding another use for it than the use I put it to, so much more consciously and scrupulously, in fiction. What sort of diary should I like mine to be? Something loose knit and yet not slovenly, so elastic that it will embrace anything, solemn, slight or beautiful that comes into my mind. I should like it to resemble some deep old desk, or capacious hold-all, in which one flings a mass of odds and ends without looking them through. I should like to come back, after a year or two, and find that the collection had sorted itself and refined itself and coalesced, as such deposits so mysteriously do, into a mould, transparent enough to reflect the light of our life, and yet steady, tranquil compounds with the aloofness of a work of art.”

Virginia extols the virtues of fine-tuning the art of writing and editing via private jottings: “. . . the habit of writing thus for my own eye only is good practice. It loosens the ligaments”.

Talking of ligaments brings to mind Leonardo da Vinci’s extensive notebooks of his sketches and experiments; they are a living record of a brilliant mind.

So, keep jotting, re-reading and editing in a notebook, diary or journal.

PS. Sorry, I broke my own rule of confining each topic in this series to 500 words . . . blame Virginia!

Next topic: